I’m pleased to announce that a newly-acquired Mystery Object has taken my Random Treasure researches to an unprecedented height of obscurity and unfashionableness. Or an unprecedented depth.

Here’s a scenario: imagine that it’s the early 19th century and you’re visiting a museum. Behind glass in a display case you espy a small, ancient, precious, unique, exquisite, priceless ivory carving, You know you won’t be permitted to touch it, but you desperately want to study it closely at your leisure. Or perhaps you wish to sharpen up your perspective drawing skills by sketching it.

But there’s a problem. Today, you can simply whip out a digital SLR camera or a mobile phone and take instant high-resolution snaps from several different angles. But you couldn’t then. Neither could you go to the museum shop and buy a postcard or a catalogue. And you certainly couldn’t go home and google up some images. Because, of course, museum shops haven’t been invented yet. Neither has the internet, and neither has photography.

If you’re lucky, you might be able to find a drawing or a painting of the desired ivory carving, but how can you know for certain that its image as filtered through the artist’s eye is accurate and true? And what changes and compromises has the artist needed to make in order to transpose the appearance of the object from three dimensions to two?

Or the scenario might work the other way around. You might see an engraving or a painting of the object and want to see the real thing. But it’s on display in an overseas museum (for example, in Munich) and this is still an age when foreign travel is reserved for the very rich or the very courageous.

Luckily, a solution to these difficulties is at hand. Welcome to the forgotten world of Fictile Ivory.

The Mystery Object under discussion in this blog post was (for me) the standout item in a mixed box of stuff bought a few weeks ago in the auction room in Dunfermline, a busy town (lately granted city status) a few miles to the north of my home city of Edinburgh. Also in the box: two Swedish mid-century candle-holders, one in sheet brass, one in ceramic; a small unused painter’s palette in mahogany; a decorated pottery egg; a late Victorian floral tile set in a cast iron frame to form a teapot stand; and a heavy tinned copper and iron frying pan. Altogether seven miscellaneous objects. How they got into the auction sale: unknown. How they came to be lotted together: unknown.

The palette, the egg, the teapot stand and the frying pan have already gone to the hospice charity shop. The two candle-holders have been retained as useful additions to our rather tired collection of Christmas decorations. That leaves the Mystery Object.

So: what was it about this piece that prompted me to bid for it and then triumphantly to bring it home together with all the other unwanted junk in the lot? I’ll try to describe it to you as I perceived it during my first weeks of ownership, while it remained a mystery yet to be solved.

A small straight-sided lidless vessel, more oval than cylindrical in outline, 99 x 85 mm (3.9 x 3.3 inches) across the top and 78 mm (3.1 inches) tall. The walls are around 5 mm (0.2 inches) thick. Weight 280 gms (9.9 oz). The exterior colour is off-white: a considerable distance off-white in some places where there appears to be significant age-related discolouration. The interior appears to be blackened, perhaps deliberately or perhaps through exposure to heat or fire.

The material from which the vessel is made is cold to the touch and seems hard and brittle – clearly so because the object has at some time in the past been shattered into many pieces and carefully reassembled with glue. But although cold, hard and brittle, yet it doesn’t feel like ceramic. Intriguing.

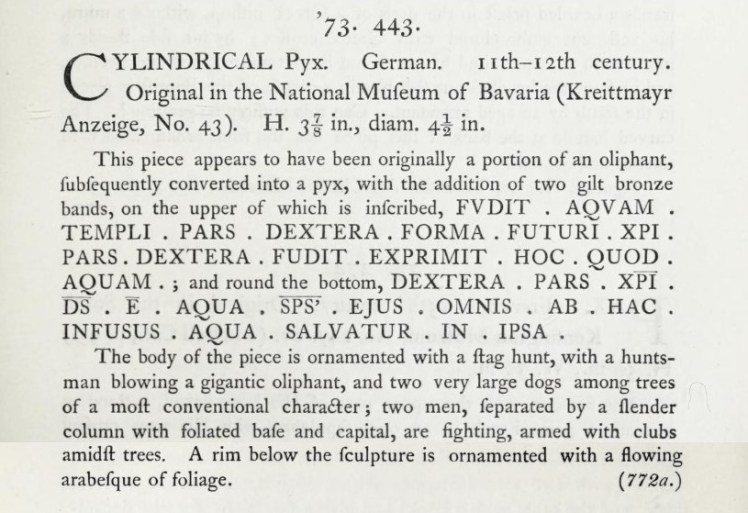

More intriguing still are the low-relief figures around the outside of the pot. A wide frieze with a huntsman blowing a curved horn; two hounds attacking a deer; two large animals (horses? lions?) rearing up at each other; two soldiers in short tunics with shields fighting each other with clubs with a pillar between them; and a couple of fanciful trees. Below the frieze, a band of vine-scrolls or arabesques. In a band around the top edge, two lines of incised lettering in upper case Roman characters, with a similar single line of lettering around the bottom edge. Most of the letters are readable, but not easily recognisable as meaningful words in any language that I’m familiar with. The relief decoration doesn’t have the appearance of having been pressed in a mould, but seems more like hand carving.

Frankly, nothing about this object rings any bells with me. At this stage I have no idea what it is, or at what date or by what process or from what material it was made. If I had to guess, I’d say it appears to be hand carved out of a single piece of stone (but not marble, perhaps limestone?). From the design of the decoration, I’d estimate that it’s very old – not an antiquity, but maybe Byzantine or at the latest mediaeval.

Although the object doesn’t ring any bells, it does set off that old familiar buzzer that I get when I start to get excited over an unknown object. I wrote in detail about this Buzz in Chapter 4 of my book Random Treasure, which you can buy here.

That’s why I had to buy this mysterious little pot. Its mystery excites me. When I get it home, I start in on my research, and immediately come up against a brick wall. Or a dead end. Or some other kind of metaphorical blockage. It’s tricky to search for information on the internet if you don’t know what search terms to begin with: I tried mediaeval carved stone pot, relief carved stone box, byzantine stone carving, and many similar permutations, finding a few images of vaguely similar relief carvings, but nothing close enough to refine my search –

Until I hit on two unfamiliar names of two unfamiliar objects. The shape and size of my pot seem to be close to that of a class of object known as a pyx or a pyxis; and the carving seems to be close to that on a class of object known as an oliphant.

A pyx is a small, lidded, straight-sided, often cylindrical vessel used in Christian religious service for the storage of communion wafers. Pyxis is a more generic term for the same kind of small storage pot but with no requirement for a liturgical use. Pyxides (the plural) have been around since classical times, and there are lots of examples in museum collections. Many of them, I discover from Google Images, are startlingly similar to my little pot, but most from the Byzantine-to-mediaeval era are carved from ivory and carry very clear Christian religious iconography, whereas my pot is in an unknown material and features hunting and fighting and nothing in the least spiritual.

An oliphant is a carved hunting horn usually made from a complete elephant’s tusk – just like the one being blown by the huntsman carved on the side of my pot. According to a very helpful short video which you can see here, many are thought to have been made in the 11th-12th centuries in the middle-east. Around 30 examples are preserved in European museums. My pot with its somewhat oval outline and secular subject matter seems to be a dead ringer for the thick end of an oliphant. Could it possibly have been adapted from a deconstructed specimen? No, of course not, because my pot isn’t made of ivory.

So near and yet so far. Some very clear leads, but try as I might I can’t find any images of comparable pyxides or oliphants made in anything other than ivory.

And then, finally, a breakthrough. I can’t recall exactly what search term I used, but I stumbled somehow upon the word fictile and everything began to fall into place.

The Oxford English Dictionary estimates that word fictile “typically occurs about 0.01 times per million words in modern written English” [i]. That means that you might see the word fictile around once in every one hundred million words that you read – so by the time that you’ve read this blog post to the end, you will probably have used up most of a lifetime’s reading of the word fictile.

When used as an adjective, the OED gives three meanings for fictile:

- Capable of being moulded, suitable for making pottery.

- Moulded into form by art; made of earth, clay, etc. by a potter.

- Of or pertaining to the manufacture of earthenware, etc.; having to do with pottery. Also (rarely) Skilled in or devoted to fictile art.

The first recorded usage of the word fictile was in 1626 by Francis Bacon. Since then, it hasn’t been used much at all but it had a brief moment in vogue during the 19th century when it was paired with the word ivory. The term was used to describe a very specific type of object: a precise and detailed facsimile, cast in plaster of paris from a mediaeval ivory original in a museum or private collection.

Yes, my little pot is a fictile ivory.

Early carved ivories are items of exceptional beauty and fragility. They became hugely appreciated from around the 1830s, as taste and fashion in architecture and design morphed from the Neo-Classical (picture the British Museum building) to Gothic Revival (picture the Houses of Parliament). Good original examples of early ivories were scarce and expensive; few came on the market, but museums and collectors wanted to show tasteful displays of them. So they procured plaster casts.

Similarly, museums wanted to display large-scale objects which couldn’t easily be brought (or looted) from distant lands, so they commissioned plaster casts of statues and architectural features – which you can still admire, especially if you visit the Cast Courts at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. And art schools wished to use classical statues as models for teaching drawing skills to students, so they bought plaster casts too. If you visit my local art school (Edinburgh College of Art, now part of the University of Edinburgh) the corridors and public spaces are still full of casts of classical statues, often jostling rather uncomfortably with the abstract and expressionist productions of to-day’s students.

Thus, the production of casts of mediaeval objects and antiquities, small and large, became quite an industry – until it was killed stone dead by the rise of photography.

Now that I knew my little pot was a plaster cast, described more pompously as a fictile ivory, the next challenge was to identify it by tracking down another one the same. Or better still, could I trace the original ivory object, maybe a pyxis, maybe an oliphant, from which my copy was cast?

I discovered that the South Kensington Museum, now the Victoria and Albert Museum, had by 1873 amassed a large collection of fictile ivories. When I say large, I mean large, with 1,166 objects listed under this title in the V&A’s current online catalogue. Unfortunately – presumably because no-one’s much interested – the compilers of the catalogue have thus far accompanied fewer than half of these entries with images. I trawled through all the illustrated entries with rapt attention but couldn’t find anything closely resembling my pot. The remainder of the collection, with no online images and only sketchy descriptions, got me nowhere.

Then I discovered an earlier listing of the V&A’s fictile ivory collection, in a hefty and long-neglected tome published in 1876 by John Obadiah Westwood, entitled A descriptive catalogue of the fictile ivories in the South Kensington museum: with an account of the continental collections of classical and mediæval ivories. Handily, there’s a digitised version of this book available online [ii], so I opened it up and tried looking for my pot. Tricky: the catalogue has 628 pages of densely printed and much-abbreviated text, and scarcely any illustrations. No joy there if you don’t know where to start searching.

Frustrated, I took a bunch of photographs of my vessel from numerous angles and subjected them to scrutiny by the artificial intelligence of Google Lens. A couple of hours later: bingo! An exact match!

If I had tried out the Google Lens matching exercise a few weeks previously or a few weeks later, it wouldn’t have produced a result. But by an amazing coincidence, an apparently identical example of my fictile ivory pyxis just happens to be currently on display in a temporary exhibition in London. The curators at the Courtauld Institute of Art have recently sorted out their collection of fictile ivories, dusted them off after many decades of obscurity and neglect, and put them on show for a short time from October 2024 to January 2025 in a small exhibition called Medieval Multiplied [iii].

The centrepiece of the exhibition is a Gothic ivory mirror case, and the purpose is “to explore how different technologies of reproduction have shaped encounters with artworks since the 19th century.”

And there, in a display case, on the second shelf down, stands …

Courtauld no. 344. Ivory pyxis, West German, 1100-1130. In the collection of Martin Joseph von Reider, Bamberg, in the 1850s, now in the Bayerisches Nationalmuseum in Munich, Germany, inv. MA 163.

Result!!! Even more excitingly, the online Courtauld exhibition listing includes a link (which you can follow here) to the original ivory pyxis from which the fictile cast was made: a beautiful early 12th century piece which resides in the Bavarian National Museum in Munich.

The Munich museum’s online description of the object reads as follows (translated by courtesy of Google Translate):

Another result!

And then, another!!! An additional exciting discovery: a further fictile copy. Armed with the knowledge that the original is in Munich, I went back to J O Westwood’s mighty 1876 catalogue, and found, on page 275, a fictile example in the V&A collection, today catalogued with accession number REPRO.1873-443 [iv]. Here is Westwood’s description:

So, to sum up, I have now traced:

- a positive identification for the original of my pot: an early 12th century ivory pyxis of uncertain origin, maybe adapted from an oliphant but converted early on for religious use, and now in the collection of a museum in Munich;

- two additional examples of the fictile reproduction of the pyxis, both in London, one in the Courtauld Institute and one in the V&A;

- detailed descriptions of the original in the Munich online catalogue and of the reproduction in Westwood’s 1876 catalogue;

- online photographic images of the original in Munich and of the Courtauld reproduction.

As a quest, this seems like a pretty successful outcome. I set out to identify an unidentified pot. I identified it satisfactorily. Perhaps I should leave it at that?

After all, it’s perfectly clear that almost no-one today (except me and a couple of museum curators) has much interest in either fictile ivory in general or in my pyxis in particular. And it’s clear that my pyxis has no value: if you look up fictile ivory in online auction catalogues, you won’t find any examples that have been sold in the recent or distant past. It isn’t a commodity. It isn’t collected. Its extreme scarcity is not accompanied by collector demand, and so it is not a marketable item.

I’ve already in this blog post repeated the word fictile more than enough times to satisfy the average reader’s lifetime consumption. Maybe at last it’s time to move on to studying something a little more mainstream?

Oh, no, not quite yet. Because mere identification isn’t enough. On close examination my pyxis poses a number of questions to which I don’t yet have answers.

- Who was the maker of this copy or replica or facsimile or reproduction?

- How were fictile ivories made?

- Why does my example differ in many details from the image and description of the ivory original in the Munich museum catalogue?

- Are the three known fictile versions (including mine) all identical to each other or are there discrepancies between them?

- And just how reliable might a fictile ivory be for use by a 19th century student or artist as a purportedly identical copy of an original?

Yes, I’m afraid there’s more to investigate and more to say about fictile ivory. Much more. Stand by, Random Treasure blog readers: another instalment will be coming your way once my investigation is complete. You’ll be gratified to learn that this might take some time.

Notes

[i] https://www.oed.com/dictionary/fictile_adj?tab=frequency

[ii] https://archive.org/details/descriptivecatal00west/page/n5/mode/2up

[iii] https://courtauld.ac.uk/gallery/exhibitions/the-courtaulds-fictile-ivories-the-cabinet-display/

Thank you for giving us a lifetime’s supply of “fictile.” I had never heard the word previously and, doubtless, will not again until you despatch episode two of this tale.

Another excellent forensic art history discourse. I feel I’ve done a seminar and must now go in search of restorative tea and biscuits (not from a fictile ivory pyx).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Andrew. Apologies for causing distress, and hope the tea and biscuits have helped to restore your equilibrium. Perhaps I should try to go easier on the F-word in the second instalment in order to avoid any further incidence of the vapours amongst my readership.

LikeLike

Fascinating story Roger. Can’t wait for second part

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you William. Don’t hold your breath for Part 2. It might be a while coming since it could involve trying to make contact with two curators in London and one in Munich.

LikeLike

Congratulations on solving some of the puzzles around this object. The Google Lens tool is indeed marvellous.

LikeLiked by 1 person

once again, a fascinating tale! eagerly awaiting the next installment! Deborah

LikeLiked by 1 person

fascinating

just a bit confused about your statement that you don’t recognise the language- it looks like Latin words and abbreviations to me. Certainly your first photo seems to show the word AQVA? Or did I misunderstand?

but l shall be on the lookout for fickle ivories and other things.

are there fickle netsukes (sp?)

cheers

john

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sorry to confuse you, John. If you compare the inscriptions in the side-by-side images near the end of my post, you’ll notice that whereas the original ivory pyxis in Munich (left) has recognisable Latin words (IPSA DEXTERA), the lettering in the same position on my fictile version (right) is mostly gibberish (IBVOM TAC ATARX).

Weird, eh? The reasons for the difference will be investigated for Part 2. Or if I can’t find any reasons, I’ll just make something up that sounds plausible.

LikeLike