Introduction

The following story is fictional, but some of the people, places and things mentioned in it are real.

- In 1872 Lord and Lady Shand leased the late 17th century mansion known as Newhailes House, in Musselburgh, near Edinburgh, from its owner Sir Charles Dalrymple.

- Buchan’s Pottery produced all kinds of utilitarian stoneware products in nearby Portobello.

- Thomas Lamb was a carter and dairyman domiciled at 8 Pipe Street, Portobello, but I don’t know if he had a son named Daniel.

- An actual 19th century silver luckenbooth brooch was offered for sale at an auction in Portobello in 2021. I bought it and wrote about it in my last blog post which you can read here.

Newhailes House is now owned by the National Trust for Scotland and is open to the public. You can read about it here. It’s a wonderful old place and well worth a visit. If you come for a house tour on a Thursday afternoon and find that your volunteer tour guide is a short, balding old bloke with a beard, spectacles and a rather pedantic delivery – that’s me.

Chapter 1

Lord and Lady Shand were delighted to move into Newhailes but found its shabby elegance rather too shabby and not quite elegant enough for their tastes. The house had been neglected by its owners in the three decades since the death of Miss Christian Dalrymple, and much work was needed to bring it up to scratch.

If he was the new owner, he wouldn’t hesitate to have the whole damp, dusty, draughty old pile renovated and fitted with the latest conveniences. But Lord Shand was a tenant. He had taken the house on a ten-year lease, furnished, and he didn’t expect to stay long-term.

As a newly-appointed Lord of Session – a judge in Scotland’s Court of Session – Alexander Shand had come a long way from his beginnings as a modest Glasgow lawyer. Although his judge’s appointment carried with it the honorary title of Lord, it didn’t give him a seat in the House of Lords. So in 1872, arriving at Newhailes, Lord and Lady Shand felt that they were still on the way up. Their ultimate objective (which they finally achieved 20 years later) was a peerage and a fine London home.

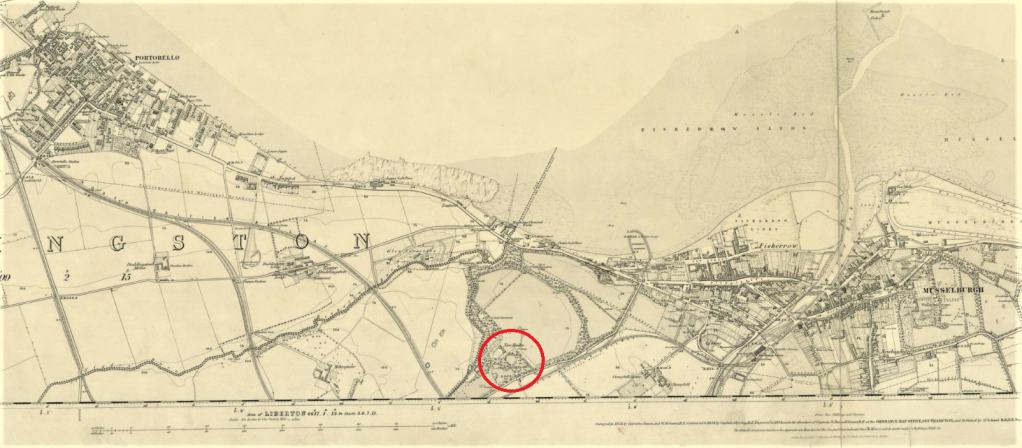

In the meantime, what could be better than being the titled tenant of Newhailes House, ancestral home of the Dalrymples, generation after generation of Scottish legal luminaries? Newhailes, with its 86 acres of ornamental grounds and its own private railway station from which Lord Shand could be conveyed (first class) the eight miles into central Edinburgh, where the Court of Session met in Old Parliament House. Newhailes, whose library had been declared by Dr Samuel Johnson to be “the most learned drawing-room in Europe”, with 7,000 books all now available not only for Lord Shand’s reference (rarely) but also to impress his visitors (frequently).

Below stairs, Lady Shand found the arrangements less impressive. The kitchens were out of date and sparsely-equipped, damp and dirty. Not much had changed, upstairs or downstairs, for more than a century.

The Shands found the agents for the house’s owners annoyingly uncooperative. The current owner Sir Charles Dalrymple spent most of his time in London as a Conservative Member of Parliament, and his instructions to his Edinburgh lawyers had been to spend as little as possible before leasing Newhailes, and to permit the tenant very little leeway to make his own changes to the grand but mouldering house.

However, Lord Shand did manage to effect some improvements, some at his own expense and some at the expense of the owner. A new cast-iron cooking range arrived in the kitchen, a new-fangled boiler was installed to provide hot water and some heating, and a coat of fresh paint was applied to the walls of the Dining Room, the Winter Sitting Room and the Best Bedroom (with the proviso that the new paint must closely match the olive green shade of what was there before).

Improvements were also required to the staffing. A skeleton household and domestic staff had been kept on by the Dalrymples over the years when the house was rarely visited by the family; but with the Shands in residence full-time, many more hands were needed in all departments: the house, the garden, the stables, the kitchen. Lady Shand and the housekeeper conducted a genteel recruitment campaign and found it a quite simple matter to procure servants from the local Musselburgh and Portobello areas, well-trained in service and eager to work at Newhailes now that the big house was back in regular occupation.

Among the new recruits was Mary MacDonald, aged 17 years, the only daughter of the Newhailes station porter. Mary was pretty, lively and intelligent, and also ambitious, thinking herself suited to better things than the lowly kitchen-maid post to which she had been appointed. And also sensible and level-headed, ready to bide her time until an opportunity should arise for her position in life to improve.

Except on entertaining days, Mary’s life wasn’t too onerous compared to the tweeny-maid post which she had occupied since the age of 13 in a prosperous local merchant’s villa. In between preparing vegetables in the scullery, washing up after the cook, scrubbing tables, swabbing floors, keeping the range stoked and serving meals in the servants’ hall, she found moments to daydream about her future. What lay ahead for her? To remain in service and become a lady’s maid or even a housekeeper, or to fall in love and marry a fine young laddie with bright prospects?

While Mary was musing, Cook was fuming. The kitchen simply wasn’t well enough equipped to meet the household’s catering needs. In particular, a good supply of utilitarian crockery was lacking for oven cooking, food storage, and preserving, and Cook just happened to know of a local supplier. Her brother-in-law was an overseer at Buchan’s pottery in Portobello, and his prestige with his employer would doubtless be enhanced if his wife’s sister’s connection with Newhailes resulted in a substantial order.

With permission from Lady Shand, the order was placed, for several dozen heavy stoneware cooking pots, storage jars and pitchers in multiple sizes. They were delivered to the house, carefully packed in straw in three wooden crates, in the back of a cart whose elderly horse was driven by Danny Lamb.

Danny was the 21-year-old only son and heir of Thomas Lamb, carter and dairyman, 8 Pipe Street, Portobello. Bright, good-looking, ambitious, eager to take over from his unimaginative father and build up the business. A carrier’s firm with two old horses pulling two old carts wouldn’t do for Danny. The tradesman’s entrance wasn’t for him – Danny knew he was cut out for great things.

Danny had made deliveries to most of the big houses in the area but had never been to Newhailes, the grandest of them all. The estate was just a couple of miles from his home but he had had no reason to go there because it had been mostly unoccupied for several years. Arriving first at the stables, he was shown by a lad to the entrance to the servants’ tunnel and told to ring the bell there.

Which he did, and after a long wait the door was opened for him by Mary.

Mornin’, hen, brought some crocks from Buchan’s.

Oh aye, bring them in.

It’s a big box – dae ye hae a barra?

No, jist carry it in yersel’.

The dim tunnel that Danny could see stretching out behind Mary looked endless. How annoying that there was no barrow handy, and how annoying that he hadn’t thought to bring his own barrow in the back of the cart. But by the time he had pulled the first heavy crate down from the cart, hoisted it on his shoulder and lugged it a few feet along the tunnel, he was feeling quite pleased with himself. First, carrying the crate allowed him to show off his strength and fitness to this very attractive young kitchen maid. Second, adopting an unnecessarily slow pace allowed him to spend a little extra time in idle chat with her. Third, the effort rendered him eligible for a short sit-down in the kitchen with a glass of lemonade kindly offered by the cook. Who then instructed Danny to pick up the crate from the middle of the kitchen floor and move it to the scullery, and instructed Mary to open it, check its contents against the delivery note, dust the straw off the crocks and take them back through the kitchen for storage in the pot store.

While gallantly assisting Mary in these endeavours, Danny had a bright idea. He hadn’t yet mentioned that the two additional crates to complete the order were on the back of his cart, and saw no reason to do so today. If he pretended that the two other boxes were for delivery to another address, he had an excuse to come back to Newhailes twice more, to get to know the kitchen maid better, and to learn more about this house – so unlike any other house he had ever seen – and its occupants.

By the third visit, Danny (who now remembered to bring his own barrow) was comfortable below stairs at Newhailes. Cook was welcoming, the other servants nodded to him in a friendly way, and Mary always seemed able to find time and reason to invite him into her scullery to chat while she worked.

Danny found reasons for further visits. One day, while the Shands were away from home with their personal servants, and the butler, footmen, housekeeper and housemaids were all occupied with some project or other in the stables, Mary and Danny explored the Great Apartments on the main floor of the house: the Vestibule with its rococo plaster work; the Winter Drawing Room (striking painting of a young girl over a magnificent marble mantelpiece); the Best Bedroom (canopied bed with bright yellow embroidered silk hangings); the Dining Room (huge table, portraits of bewigged ancestors); the Chinese Sitting Room (pretty furniture and ornaments); the China Closet; and the vast Library, by far the biggest room either of them had seen in anyone’s house, twenty feet high and with all four walls intimidatingly lined floor-to-ceiling with books.

How wonderful, how magical, thought Mary, how much would I love to be a grand lady in a house like this – or at least to be the housekeeper in charge of keeping these rooms clean and tidy.

How unfair, how unjust, thought Danny, how obvious that this house was built on the backs of poor workers like me and my father, how much do I want to grind these fancy rich folk beneath my heel – and own this house myself.

Danny became a familiar figure below stairs. Yes, he did distract Mary from her work, but he was such a good-natured and cheerful lad, and always so willing to lend a hand with fetching and carrying, that Cook always welcomed him with a cup of tea or a glass of cordial whether he arrived with a delivery or just happened to be passing by.

The playful banter between Danny and Mary developed over the following months into close companionship and then into love. They began to plan a future together. They were well suited: she wanted to leave service and get a better life, he wanted to take over his father’s business and build it up. A fine young couple with great potential. Neither set of parents was likely to raise any objection. All was set fair for their future as Danny planned his marriage proposal. He would take Mary out to the bents for a Sunday afternoon picnic and would find a quiet spot among the sand dunes to propose to her.

The playful banter between Danny and Mary developed over the following months into close companionship and then into love. They began to plan a future together. They were well suited: she wanted to leave service and get a better life, he wanted to take over his father’s business and build it up. A fine young couple with great potential. Neither set of parents was likely to raise any objection. All was set fair for their future as Danny planned his marriage proposal. He would take Mary out to the bents for a Sunday afternoon picnic and would find a quiet spot among the sand dunes to propose to her.

All he needed now was something to give to his true love as a token of his adoration. He set his mind on presenting her with a luckenbooth brooch – but it would have to be a much bigger and shinier one than the modest example which his mother had received from his father on a similar occasion, and which she had proudly worn every day since then.

But a luckenbooth brooch costs money, and for Danny money was always in short supply. He liked to dress himself smartly when he wasn’t working, and enjoyed noisy evenings out with the boys. Result: no cash for buying presents, and little prospect of saving any cash without making significant economies in his lifestyle. For Danny this would mean sacrificing activities which he considered essential to a young man on the up-and-up. It was not an acceptable option: an alternative source of income was required.

One day while visiting Mary in the Newhailes scullery, Danny got a lucky break. He was being rather a nuisance, pestering her for kisses while she was trying to bone a brace of rabbits for the staff’s evening meal. For a few moments of peace and quiet she sent him to get one of the heavy stoneware cooking pots out of the pot store, and told him place it on the big kitchen table for cook to start making the stew.

On the way to the pot store, Danny noticed that the door of the silver cupboard had been left open. Presumably the Butler had scurried upstairs to the Library in response to a peremptory call from Lord Shand. In a matter of seconds, Danny had leapt inside, selected a small silver card tray or salver which would fit invisibly into the inside pocket of his jacket, and continued with his errand.

Naebody’s gonnae miss one wee piece o’ siller, he reasoned (correctly, as it turned out). They rich folk have far too much stuff and I have naething. If they want to keep a hold o’ their valuables they should guard ‘em better. Thus unilaterally adopting the socialist principle of redistribution of wealth, Danny wasn’t especially troubled by conscience or compunction in relation to this theft.

Here was his plan: to take the silver tray into a silversmith’s shop and ask the smith to melt it down to make a luckenbooth brooch for Mary. The silversmith could keep any leftover metal as his payment. Simple. Effective. Infallible.

But it didn’t quite work out as planned.

The first silversmith, whose shop was in Portobello High Street, took one look at the silver tray and said: I know you, you’re Tam the carter’s lad. Where did ye get this from, ye thievin’ bastard? Get oot o’ my shop noo or I’ll tell yer Dad and I’ll tell the polis!

The second silversmith, whose shop was in Musselburgh High Street, looked closely at the silver tray and said: There’s a family crest engraved on this. It’s frae Newhailes, isn’t it? I’m no friend of the Dalrymples so I’ll not ask any questions, but I’m no’ gonnae touch it. I couldn’t anyway because it doesn’t have an assay mark so it isn’t sterling silver. This’ll be low-grade stuff sent back from one of they Dalrymple cousins livin’ like nabobs in India. Away ye go, laddie.

The third silversmith didn’t have a shop. He worked from a brick outhouse in the back of his tumbledown cottage down a dingy alley in Prestonpans. Danny heard from someone in the pub that he wasn’t the kind to ask questions. Aye, I’ve got a luckenbooth mould. I’ll make a nice one for ye oot o’ this wee siller tray and it’ll no’ cost ye anythin’ other than the rest o’ the siller. Come back next week.

Returning a week later, Danny was disappointed to find that the brooch wasn’t quite the luxury item that he had had in mind. Although big and shiny, it felt lightweight and looked paper-thin, and the engraved decorations were crude and sketchy. Danny left thinking that the Prestonpans silversmith had earned himself a lot of scrap silver for very little effort and less expertise. But the brooch would have to do. Hopefully Mary would be so taken by its size and flashiness that she wouldn’t look too closely at the quality.

Returning a week later, Danny was disappointed to find that the brooch wasn’t quite the luxury item that he had had in mind. Although big and shiny, it felt lightweight and looked paper-thin, and the engraved decorations were crude and sketchy. Danny left thinking that the Prestonpans silversmith had earned himself a lot of scrap silver for very little effort and less expertise. But the brooch would have to do. Hopefully Mary would be so taken by its size and flashiness that she wouldn’t look too closely at the quality.

On a sunny Sunday afternoon in June 1873, Danny and Mary set out for their picnic. He had made elaborate preparations. The better of his father’s two carts had been specially swept out for the occasion, and the old brown mare had been combed and dressed in her finest trappings. Mrs Lamb had packed an enormous lunch in a wicker hamper. Her son had told her about his plan and she approved, and was impressed when he showed her the brooch. But she wondered to herself where her son had found the money to buy Mary such a lovely thing.

Mary had dressed carefully and was looking her prettiest, well aware of the purpose of the outing and of Danny’s intentions – and ready with her answer for when the big question was asked. With the Shands away visiting, she had directed him to meet her not at the servant’s entrance but at the front of Newhailes. On his arrival, she left the house by the front door and swept down the stone staircase like a great lady.

A half-hour ride took the couple to Longniddry Bents, where they headed for the dunes, Danny carrying the heavy lunch basket and Mary carrying a blanket for them to sit on. Finding a suitably secluded spot took some time, and when they finally settled they were breathless from exercise, heat and anticipation.

With much on their minds, they found that their conversation over the excellent picnic lunch was unusually hesitant and punctuated with awkward silences. But after filling themselves with cold sliced ham and beef, cheese, buttered bread, potted hough and chutney, followed by iced buns, all washed down with ginger beer, they both knew that now was the moment to move forward with the main purpose of the outing.

With much on their minds, they found that their conversation over the excellent picnic lunch was unusually hesitant and punctuated with awkward silences. But after filling themselves with cold sliced ham and beef, cheese, buttered bread, potted hough and chutney, followed by iced buns, all washed down with ginger beer, they both knew that now was the moment to move forward with the main purpose of the outing.

Taking courage from a concealed swallow of whisky from his hip flask, Danny withdrew from his jacket pocket the small package containing the luckenbooth brooch.

Mary, I got ye this brooch. Will ye marry me?

Really enjoyable, thank you. As part of my research for my book (Ponting’s maternal uncles worked in Birmingham’s jewelry quarter) I bought a ring made from a spoon – who says re-purposing/up-scaling is new?

LikeLike

Thank you, Anne. One reason why early objects made from precious metals are scarce is that they were melted down and re-fashioned multiple times over millennia as fashions changed. I think I might have read somewhere (or perhaps I just made it up?) that just about all new gold jewellery bought today is likely to contain traces of metal mined in ancient times. This doesn’t happen with ceramics, which will persist (complete or in shards) for thousands of years. You know where you are with ceramics.

LikeLike