Unusually I have taken a risk. Partly to give myself a bit of a lift during a very dreary period of lockdown, and partly to furnish subject matter for this new Random Treasure blog piece.

Here’s what I did one Saturday morning a couple of weeks ago. On the strength of nothing more than one grainy photograph and a very vague catalogue description, I bid for and won an auction lot of some fifteen (yes, 15) pieces of pottery. The photograph is below, accompanied by the description:

The estimated price in the catalogue was £30-50, and I secured the lot for the bottom estimate of £30. That’s £2 per piece. The auction house was the one nearest my home, where I have had many good finds in the past. However, on this occasion I did not view prior to purchase, for the simple reason that viewing is not permitted under the present Covid restrictions; and I did not avail myself of the opportunity offered by the auctioneer for online viewing via a Whatsapp video call.

No, I just decided to go for it, with no idea other than the photo and the description of what I might be getting. However good or bad, however interesting or boring my purchases might turn out to be, I determined that the main part of this piece will comprise a report upon my findings.

The nature of the risk that I took with this precipitate action was three-fold:

- I might have bought a load of colourful junk which I wouldn’t even be able to get rid of because the charity shops are all closed.

- I might have wasted thirty quid (plus commission).

- I might, by vowing to myself to write about these objects in a new blog piece, put myself on the brink of literary suicide by boring either my readers or myself to death. Possibly both.

In the 48 hours between bidding and collecting the lot, I looked more closely at the photograph, and the more I looked, the greater my forebodings. See that big plate with the blue tulips (I said to myself): it’s certainly Turkish, but is it 16th century Iznik (value £20k) or 20th century Kutahya tourist ware (value nothing)? The larger bowl on the right: early Scottish spongeware or recent industrial tat? The blue-and-white Japanese bowl: Edo period Arita porcelain or mass-produced junk? And the closer I looked, the more I worried that the latter might apply in each case. This could get difficult.

Modern tourist ware plate from Kutahya, Turkey

Modern British Adams “Old Colonial” bowl

Modern mass-produced Japanese Arita bowl

Iznik dish, 1575-1580, Victoria and Albert Museum https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O67313/dish-unknown/?carousel-image=1

Scottish Verreville Pottery dish, 19th century, image sourced from https://www.scottishpotterysociety.org.uk/verreville/verreville-gallery/

Arita dish, Edo Period (1615-1869), Victoria and Albert Museum https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O235223/dish-unknown/

I collected my purchases on the Monday, and sure enough the news was Bad. Yes, every item in the lot was modern, all quite pretty but almost none of any interest to a collector. Yes, I had wasted my money. Yes, you will be bored stiff if I photograph and describe each piece in detail, because, yes, all of my worst forebodings had come to pass. Twelve pieces went directly into the charity shop box, and I’m confident that when the charity shops re-open they will sell very well. A pair of cheerful blue Indian pottery candlesticks will be kept to add colour to the summer house interior. And that just leaves just one piece for further study, which is slightly interesting.

I collected my purchases on the Monday, and sure enough the news was Bad. Yes, every item in the lot was modern, all quite pretty but almost none of any interest to a collector. Yes, I had wasted my money. Yes, you will be bored stiff if I photograph and describe each piece in detail, because, yes, all of my worst forebodings had come to pass. Twelve pieces went directly into the charity shop box, and I’m confident that when the charity shops re-open they will sell very well. A pair of cheerful blue Indian pottery candlesticks will be kept to add colour to the summer house interior. And that just leaves just one piece for further study, which is slightly interesting.

So, what should I do?

- Abandon this blog post and delete everything I have written so far, so you won’t ever know about my promise to write about this auction lot and no other?

- Keep going and try to write an amusing and diverting post about a load of intrinsically boring pots?

- Take a trip into the attic, choose a dozen pieces of interesting Continental pottery from there (which I could do, believe me), and pass them off to you as my new lucky auction finds?

- Try to pad out what little I know about the single slightly interesting pot as the sole topic for the remainder of this blog post?

Forget (a) above. I have already laboriously put down more than 600 words in this piece, and you expect me to abandon it? Junk it? Trash it? No way!

As for (b) above, although this piece is about risk, that’s a risk too far. The Random Treasure blog has too few readers for me to risk alienating any of them by deliberately publishing stuff that even I think is boring.

Option (c) also has to be dismissed, because strict honesty is my watchword, and, tempting as it might be, I would be much too conscience-wracked to pass off old attic-dwelling pieces as new finds.

Which leaves option (d): to focus in the remainder of this piece on the single interesting piece which came home in my hoard. OK. I’ll give it a go. But this in itself is problematic, firstly because if I proceed in this way, it will be necessary to diverge from my objective by bringing in some other pieces for comparison which weren’t included my new auction lot. And secondly, because out of all of the ceramic items which I have encountered or imagined in a lifetime of fascination with pottery, I am least competent to provide an extended commentary upon this particular object.

It is a Japanese tea-bowl. Now, when it comes to writing about Japanese ceramics, it’s best for me to keep very, very quiet and not even to make the attempt. I haven’t visited Japan (although I would like to). I have no knowledge of the Japanese language, and only a hazy layperson’s appreciation of the country’s history and culture. I haven’t studied Japanese ceramics, and am not a collector of them. I have no desire to be accused of cultural appropriation. Thus, it is wholly inappropriate for me to express opinions or make pronouncements upon any matter concerning Japanese ceramics.

About the only thing I do know is what most or all antiques enthusiasts already know: that the vast bulk of Japanese objects in general and ceramics in particular which have fetched up on these western shores in the past 150 years have very little in common with the domestic taste, fashion, tradition and culture of the Japanese people. Most artefacts imported into Europe and America since around 1870 have been made by Japanese craftspeople to fulfil an insatiable market demand for Japonisme, a romantic Western idea of what Japanese art and craft should look like.

Having prefaced my description of this tea-bowl with such a lengthy disclaimer, such an elaborate confession of my total lack of qualification to expatiate upon this subject, I guess that now is the moment for me either to put up or shut up. Well, here goes…

The single slightly interesting object in my auction hoard is a small steep-sided bowl 122 mm in diameter and 78 mm tall. It is a tea-bowl or chawan. Or is it? It seems (according to some sources) that while all tea-bowls come under the generic heading of chawan, not all chawan are necessarily tea-bowls, because the term also covers rice bowls, and for aught I know, other kinds of bowls too.

Moreover, there appears (according to other sources) to be a distinction between (on the one hand) tea-bowls which come under the generic heading of tea-bowls, and (on the other hand) a specialised subset of tea-bowls which are reserved for the consumption of matcha tea as essential components of the traditional tea ceremony.

“Chawans are available in a wide range of sizes and styles, and different styles are used for thick and thin tea. Shallow bowls, which allow the tea to cool rapidly, are used in summer; deep bowls are used in winter to keep the green-tea hot for longer time. Bowls are frequently named by their creators or owners, or by a tea master. Bowls over four hundred years old are said to be in use today, but probably only on unusually special occasions. The best bowls are thrown by hand, and some bowls are extremely valuable. Irregularities and imperfections are prized: they are often featured prominently as the “front” of the bowl.” [1]

My chawan is made in a cream-coloured non-translucent porcelain, and covered with a clear glaze outside and inside, except for the exterior base and footrim which are unglazed. The outer surface is simply and sparsely decorated with maple leaves and carnation flowers in green, white and orange overglaze enamels, with gold outlines. Beside the footrim there is a stamped potter’s seal.

I don’t think my bowl has a name, and it’s not old – almost certainly made in the second half of the twentieth century or later. Neither do I think that it is a priceless and rare treasure. It is, however, undoubtedly a tea-bowl designed for use in the matcha tea ceremony, and it’s an individually-made and signed artefact from a skilled potter. All of which makes it a rather special object.

Having posted its picture on the very helpful Facebook Collecting Japanese Ceramics and Arts group page, I can be a little more specific. It has been confirmed by an expert as “not a simple chawan, but a tea bowl”. There are many different variations on the tea ceremony, and very many different types of chawan, but this one has been identified as Kiyomizu ware made in Kyoto: you can tell this from the type of clay and glaze used, and from the type of decoration. The combination of autumn and spring motifs in the decoration indicate that it is suitable for use all year round except in the summer. The signature has been read by one expert as 練山, with the potter’s name transliterated as Renzan, and by another expert as 連山 or Neriyama. But the former mark is associated with Satsuma ware and not with Kiyomizu ware, and I can’t find any record of the name Neriyama in connection with pottery from Kyoto. So: maker unidentified.

Having posted its picture on the very helpful Facebook Collecting Japanese Ceramics and Arts group page, I can be a little more specific. It has been confirmed by an expert as “not a simple chawan, but a tea bowl”. There are many different variations on the tea ceremony, and very many different types of chawan, but this one has been identified as Kiyomizu ware made in Kyoto: you can tell this from the type of clay and glaze used, and from the type of decoration. The combination of autumn and spring motifs in the decoration indicate that it is suitable for use all year round except in the summer. The signature has been read by one expert as 練山, with the potter’s name transliterated as Renzan, and by another expert as 連山 or Neriyama. But the former mark is associated with Satsuma ware and not with Kiyomizu ware, and I can’t find any record of the name Neriyama in connection with pottery from Kyoto. So: maker unidentified.

That’s all I know. I don’t collect Japanese pottery, but this tea-bowl is a lovely object I shall be proud to keep it in my collection, along with perhaps 20 or 30 other pieces of Japanese pottery which I also have not collected. They simply accumulate. They accrete. I can’t explain their presence in my house. They just sort-of come home with me from expeditions to charity shops and auctions. There’s nothing I can do about it.

I’ve sorted out some more Japanese bowls from miscellaneous shelves, cupboards and hidey-holes, simply to give you an idea of the variety of Japanese ceramics which can be acquired for practically nothing within a mile or two of my Edinburgh home. I have no idea how any of them arrived here, but it’s safe to say that the majority don’t fit in with the accepted Western view of what Japanese pots should and do look like. Sadly, I can’t tell you very much about any of them, and neither, for all the reasons given above, should I attempt to do so. Anything which sounds vaguely knowledgeable in the following paragraphs is derived from information provided by the Facebook experts, and any errors are provided by me.

This bowl is of a type which will be familiar to many readers. They are universally described by antique dealers and auction cataloguers as “Japanese Imari”, and if you see this description you know exactly what to expect. This ware was made from the 17th century in the area of Arita in in the former Hizen Province, northwestern Kyūshū, specifically for export to the west. In the early period the quality was exceptionally good and current auction prices for early pieces are very high. In the later 19th century, incredibly vast quantities were made to satisfy European demand, and quality was extremely variable. As a result today you see plenty of “Japanese Imari” pottery selling at very cheap prices. This example came from a charity shop some years ago, and in terms of quality is close to the bottom of the scale, made in thick, dull porcelain, crudely decorated, and poorly glazed and finished. Its “snake’s-eye” base is slightly unusual and probably dates it to a little before the end of the 19th century. It’s cheap. It’s kitsch. I love it.

This bowl is of a type which will be familiar to many readers. They are universally described by antique dealers and auction cataloguers as “Japanese Imari”, and if you see this description you know exactly what to expect. This ware was made from the 17th century in the area of Arita in in the former Hizen Province, northwestern Kyūshū, specifically for export to the west. In the early period the quality was exceptionally good and current auction prices for early pieces are very high. In the later 19th century, incredibly vast quantities were made to satisfy European demand, and quality was extremely variable. As a result today you see plenty of “Japanese Imari” pottery selling at very cheap prices. This example came from a charity shop some years ago, and in terms of quality is close to the bottom of the scale, made in thick, dull porcelain, crudely decorated, and poorly glazed and finished. Its “snake’s-eye” base is slightly unusual and probably dates it to a little before the end of the 19th century. It’s cheap. It’s kitsch. I love it.

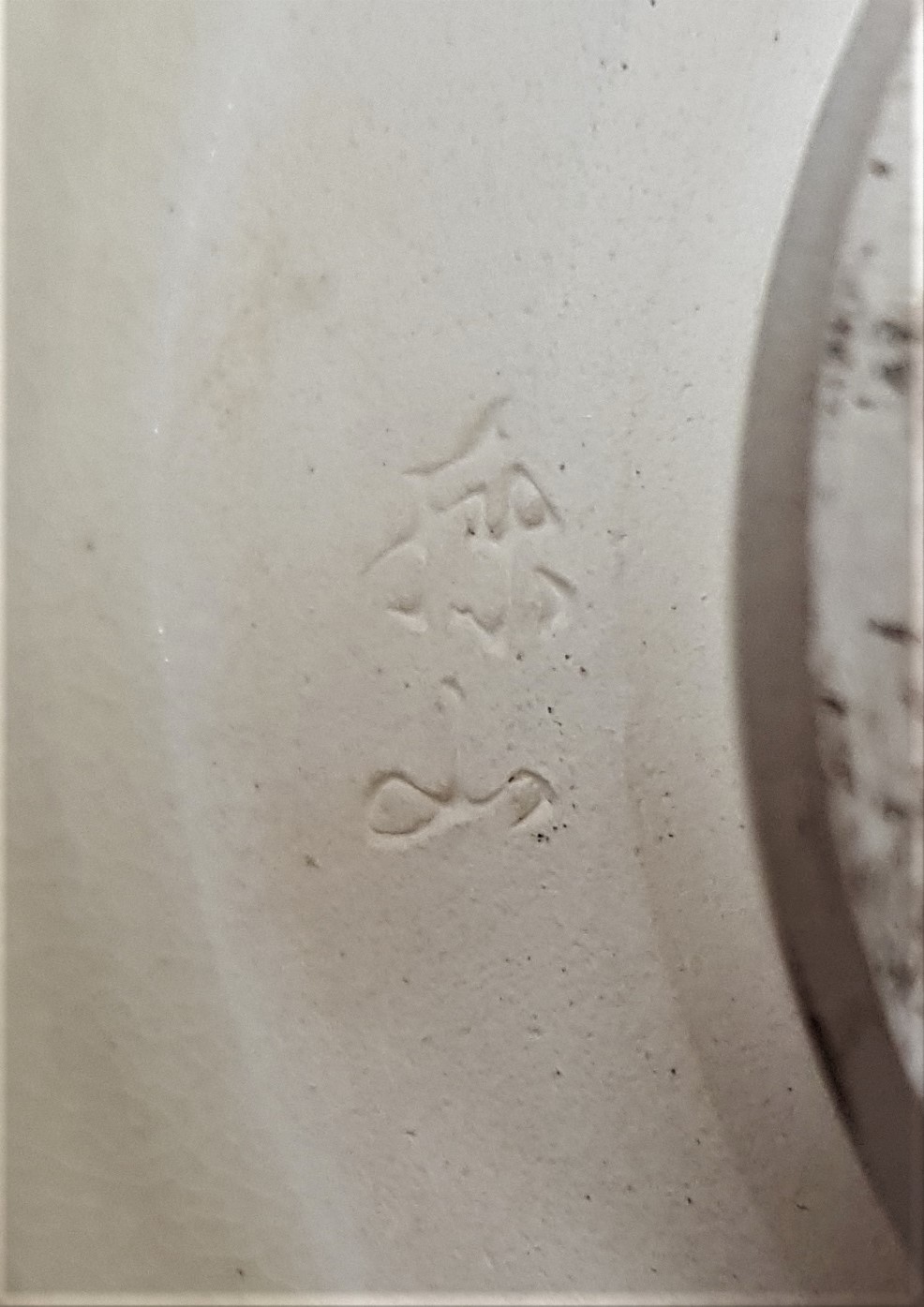

The type of glaze on this teabowl or chawan is called shino, more precisely nezumi shino (i.e. with an inlaid white pattern). It has an impressed seal beside the footrim, from which (thanks again to Facebook experts) I know that it was made at the Shuzan-gama kiln by the kiln master Kato Shuzo. The Shuzan kiln is in the Mino area in the south-eastern part of Gifu Prefecture. Earthenware pottery looking very much like this has been made in the Mino area since at least the 16th century, but this example was made in the late 20th century, and it appears from this link that the potter is still very much alive: http://news.tablin.info/archives/1194.

The type of glaze on this teabowl or chawan is called shino, more precisely nezumi shino (i.e. with an inlaid white pattern). It has an impressed seal beside the footrim, from which (thanks again to Facebook experts) I know that it was made at the Shuzan-gama kiln by the kiln master Kato Shuzo. The Shuzan kiln is in the Mino area in the south-eastern part of Gifu Prefecture. Earthenware pottery looking very much like this has been made in the Mino area since at least the 16th century, but this example was made in the late 20th century, and it appears from this link that the potter is still very much alive: http://news.tablin.info/archives/1194.

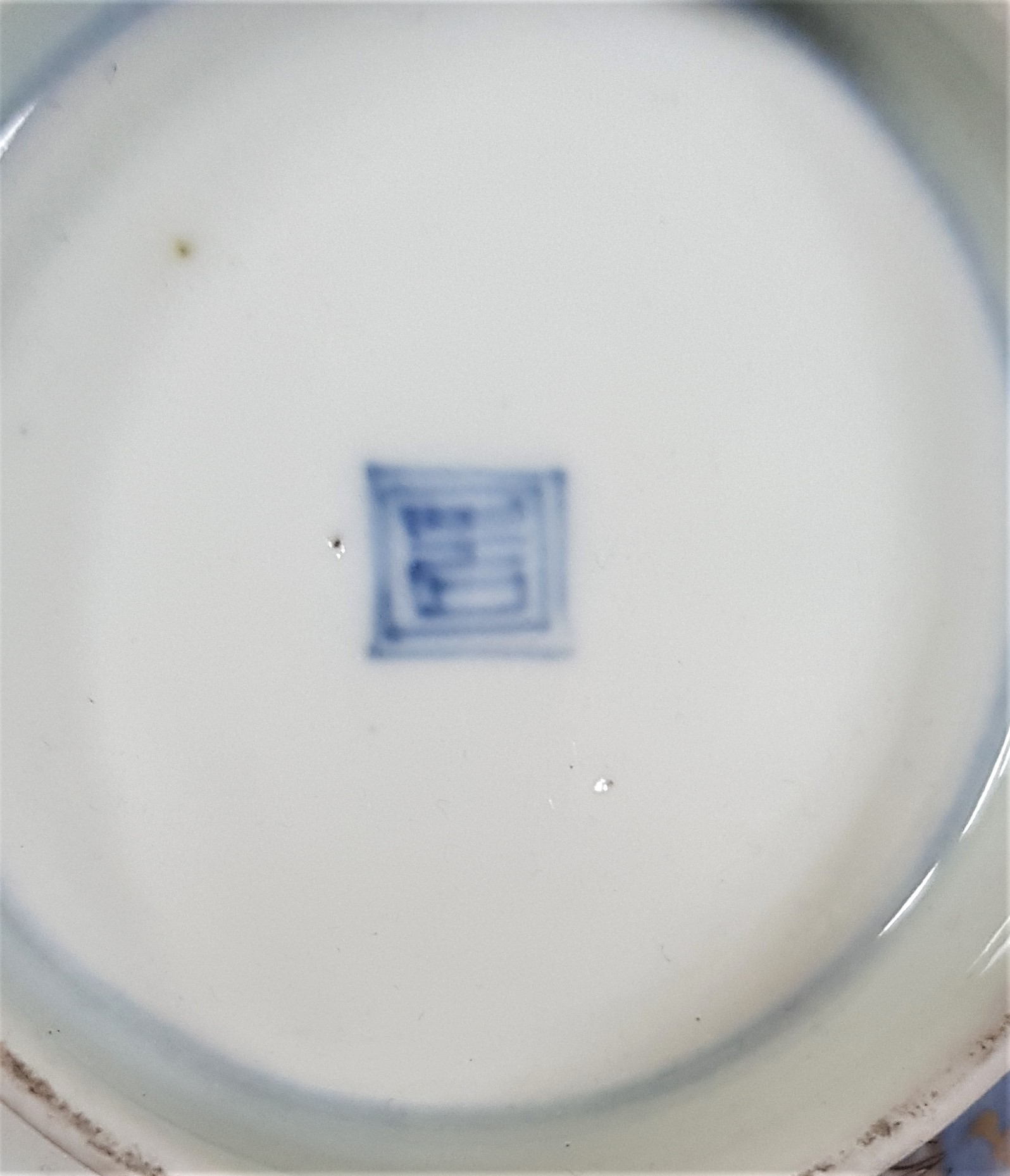

This pretty rice bowl is made in a very fine bluish-white porcelain which has a bell-like ring when flicked with a fingernail. The simple decoration is in underglaze cobalt blue. The impressed mark on the underside is thought to read Rinsen, which is the name of a kiln at Hasami in Nagasaki Prefecture. Porcelain manufacture has been taking place in Hasami for 400 years. The V-shaped decorations are double pine needles, a symbol of matrimony, so it might be that this bowl was part of a set given as a wedding present.

This pretty rice bowl is made in a very fine bluish-white porcelain which has a bell-like ring when flicked with a fingernail. The simple decoration is in underglaze cobalt blue. The impressed mark on the underside is thought to read Rinsen, which is the name of a kiln at Hasami in Nagasaki Prefecture. Porcelain manufacture has been taking place in Hasami for 400 years. The V-shaped decorations are double pine needles, a symbol of matrimony, so it might be that this bowl was part of a set given as a wedding present.

A covered rice bowl in fine white porcelain with underglaze blue and overglaze polychrome and gold decoration in the Kakiemon style depicting koro (ornate incense-burners) between flowering cherry and bamboo trees. This is Arita ware of high quality, made in the 20th century, but I wouldn’t like to say if it was made in the Meiji (1868-1911), Taisho (1911-1926) or Showa (1926-1989) period. Most probably the last. The lid has a seal mark, currently unidentified, which is similar to but frustratingly not quite the same as the mark of the Aoki Brothers of Hizen.

A covered rice bowl in fine white porcelain with underglaze blue and overglaze polychrome and gold decoration in the Kakiemon style depicting koro (ornate incense-burners) between flowering cherry and bamboo trees. This is Arita ware of high quality, made in the 20th century, but I wouldn’t like to say if it was made in the Meiji (1868-1911), Taisho (1911-1926) or Showa (1926-1989) period. Most probably the last. The lid has a seal mark, currently unidentified, which is similar to but frustratingly not quite the same as the mark of the Aoki Brothers of Hizen.

This earthenware chawan is of a type called oribe, named after its very characteristic green glaze. The brown brushwork is also typical of this type of ware, which looks quite crudely-made but in fact is a very sophisticated product with at least four hundred years of traditional design behind it. It is also called Mino ware, after the area of Japan where it was originally made, and also called Seto ware from the city in Aichi Prefecture where it is now made. Confused? Me too. The bowl bears an impressed seal mark near its base which reads 五陶, the mark of Kato Goto, a well-known Seto potter.

This earthenware chawan is of a type called oribe, named after its very characteristic green glaze. The brown brushwork is also typical of this type of ware, which looks quite crudely-made but in fact is a very sophisticated product with at least four hundred years of traditional design behind it. It is also called Mino ware, after the area of Japan where it was originally made, and also called Seto ware from the city in Aichi Prefecture where it is now made. Confused? Me too. The bowl bears an impressed seal mark near its base which reads 五陶, the mark of Kato Goto, a well-known Seto potter.

I believe this unmarked shallow stoneware dish to be a typical example of ware from Mashiko, a town in Tochigi Prefecture where pottery making started in the mid-19th century. After the potter Shoji Hamada settled there in 1924, Mashiko became famous as a centre of the Mingei movement.

“Upon returning to Japan, Hamada met the philosopher and scholar of religion Yanagi Sōetsu and the potter Kawai Kanjirō. The three are credited with coining the word Mingei (folk craft), a condensed form of the term minshūteki kōgei. This marked the beginning of the Mingei movement, which espoused appreciation of the beauty of common household objects made by anonymous craftspeople” [2].

Since then the Mingei philosophy has become hugely influential in Japan and throughout the world in the growth and popularisation of folk art. My shallow dish represents the movement superbly: it’s plain, simple, useful, robust, elegant, unattributable to a named artist, and beautiful. Tip a small pile of fresh cherries into the centre of it, and see it transform into a perfect still life.

Since then the Mingei philosophy has become hugely influential in Japan and throughout the world in the growth and popularisation of folk art. My shallow dish represents the movement superbly: it’s plain, simple, useful, robust, elegant, unattributable to a named artist, and beautiful. Tip a small pile of fresh cherries into the centre of it, and see it transform into a perfect still life.

My last bowl is a chawan, but its maker would have simply called it a bowl. It was made in England by an English potter who exerted a lasting influence on Japan, and is widely revered there today. By contrast, he’s merely famous in Britain. The quotation about Shoji Hamada in the last section described Hamada’s return to Japan and his activities in Mashiko. But where was he returning from? From St Ives in Cornwall, England, where he had spent three productive years working in partnership with the potter Bernard Leach. Leach had lived for many years in Japan and was closely involved with Hamada and Yanagi in the development of the Mingei philosophy. He made this simple stoneware bowl in St Ives probably around 1950. It has been broken and repaired, which is OK with me because it meant I could afford to buy it.

My last bowl is a chawan, but its maker would have simply called it a bowl. It was made in England by an English potter who exerted a lasting influence on Japan, and is widely revered there today. By contrast, he’s merely famous in Britain. The quotation about Shoji Hamada in the last section described Hamada’s return to Japan and his activities in Mashiko. But where was he returning from? From St Ives in Cornwall, England, where he had spent three productive years working in partnership with the potter Bernard Leach. Leach had lived for many years in Japan and was closely involved with Hamada and Yanagi in the development of the Mingei philosophy. He made this simple stoneware bowl in St Ives probably around 1950. It has been broken and repaired, which is OK with me because it meant I could afford to buy it.

Bernard Leach was born in China, lived in Japan and travelled extensively in Korea. As such he was qualified to speak and write (both of which he did, prolifically) about the related ceramics traditions of those countries. And as for me? No travel, no residence, no qualifications. Nothing but a small non-representative collection of pots. I’d better leave it there.

Or, perhaps, just one more word. I might just try to pick a favourite from among the eight bowls which have featured in this piece. Hmm, tricky. But yes, I think it would have to be the shino chawan made by the potter Kato Shuzo. And why? Don’t know really – but I like it enough to have featured it before in this blog, in a fairly recent post extolling the wonders of the colour orange.

Notes

Enjoyed this semi-confessional piece, Roger, thank you … but agree that your previous Japanese pieces have a gravitas to them that your new acquisition doesn’t. But I’m sure the charity shop and its customers will be very happy with your purchases, so perhaps you could just think of it as a £30+commission donation to a worthy cause, from which they will probably raise considerably more … I’ve held off purchases at the moment due to non-viewing – with one exception which I’m happy with.

Here’s to auction viewings restarting and, more excitingly, auction attendances …

LikeLike

Anne, I’m sure you’re absolutely correct in your policy of no buying without viewing. I just wish I had your self-discipline, especially since most of my non-viewed purchases during the lockdown have been spectacularly unspectacular. Is that going to stop me? Unlikely.

LikeLike

If truth be told, I did succumb to an unexamined item:

https://www.mallams.co.uk/sales/cheltenham/bs051120/view-lot/798/

I was otherwise preoccupied during the auction, but when it was unsold and the auctioneer said the seller was well-known to them, I bid at the bottom of the range. I loved he story of the ship (auspicious good fortune in hard times) – it’s not perfect, but I love the story of the ship (including the solitary goddess – the rest are gods). It’s charming and now is on the mantelpiece with the cloisonne vase (now confirmed to be not Namikawa, but lovely and loved none-the-less). So all good and feel looked-after by the gods/goddess on the ship for years to come.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Think I might have succumbed to that item too! I’ve just been reading up on the Treasure Ship Takarabune: what a lovely cheerful story. We could all do with being looked after by benevolent gods and goddesses in these difficult times.

LikeLike

Ah Roger, if you hadn’t declared that you were drawing on wider expertise from the internet you could readily have convinced me of your infinite knowledge of Japanese ceramics, so lightly do your wear your own learning and other people’s. You must be getting through to me at last, I’m really taken by the Shuzo and Leach chawans. By contrast the Mino oribe smacks of Disney to me in its decoration, I can’t take it seriously.

But the item that caught my eye in your random purchase was the fantail pigeon(?). Is that a table salt dish, or is it purely ornamental? I’m sure you’ll know and I think we need to be told.

Anyway many thanks again for lighting up the gloom of Lockdown.

LikeLike

Bob, for ‘infinite’, please substitute ‘infinitesimal’. I’m pleased you like the shino chawan and the Leach bowl (he would have been much too blunt and down-to-earth to call it a chawan), but sorry that you don’t see the charm of the oribe example. I can see now that the way I photographed it does give it a bit of a comical smiley-faced look, but generally I’m a big fan of oribe, and my recommendation is that you spend a little contemplative time among the fine collection of wares in the Met in New York, failing which you could look at their website at https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search#!?q=oribe&perPage=20&searchField=All&sortBy=Relevance&offset=0&pageSize=0.

As for the pigeon, I’ve rescued it from the charity box and had another look, and regret that I still can’t say anything positive about it. It is an individually-made and signed piece, and appears to have been made by a competent amateur potter called J Poole. But close up, it’s a bit lop-sided, and has funny eyes and a weird beak. We did think of keeping it as a small garden ornament, but decided that we already have quite enough odd-looking pigeons of the live variety inhabiting the garden.

LikeLike

Another interesting post, Roger. All the crockery in our house comes from John Lewis or similar, which makes Lot 66 look exotic and very attractive.

Best wishes, Jerry

>

LikeLike

Thank you Jerry. Yes, there are some attractive, colourful pieces in the box that’s going to the charity shop. It seems all too often that attractiveness and colourful-ness are not among the top criteria for my selection of which pieces to keep and which to jettison. Some people might think I’m more likely to give priority to weirdness and brown-ness, and it’s possible that those people are not wrong.

LikeLike