World Heritage.

If you have read Part 1 of this blog post, you know that our Courtauld Institute of Art party is on a three-day study tour in Ravenna. We’re here to see all eight of the jaw-dropping buildings from the 5th and 6th centuries which appear on the UNESCO World Heritage List, of which seven feature stunning mosaics. Plus some extra buildings too, and three museums. It’s going to be an intensive few days. Here we go.

Church of San Vitale

I briefly described the exterior of the Church in Part 1 of this blog post: octagonal, bare brown brick, heavy buttresses, small windows. From the outside it’s not a graceful or elegant building. But inside – wow! The walls and ceilings at the business end of the church are entirely covered with mosaics, and the thing about mosaics, you instantly realise, is that unlike with other pictorial art forms, they don’t fade or lose colour or lose impact over time.

Oil paintings darken through repeated coats of varnish; frescoes and water colours fade; sculptures are stripped of their unfashionable polychrome decoration; gold and silver objects are melted down and re-fashioned; stained glass distorts and degrades; images are defaced and destroyed in iconoclasms. But when a mosaic survives, it’s as fresh and bright as on the day it was finished. When a whole building survives which is lined with mosaics, it’s breathtaking. That’s why art historians and the more culturally-minded sorts of tourists flock to Ravenna.

Dull and stolid outside – but inside, the church of San Vitale is lofty, magnificent, and complex, lit in a gentle amber glow by translucent alabaster windows. Architecturally, it’s a wonder, with a high domed central area surrounded by an extraordinarily elaborate arcaded ambulatory. And then the mosaics: Christ with bishops and archangels in the apse; the Lamb of God in the ceiling supported by archangels; an arch of Apostles; Old Testament stories: Abraham, Isaac and Jacob on one side, Melchizedek on the other.

Melchizedek? Who? A minor biblical character with bit part in Genesis Chapter 14, so why does he merit an enormous square footage of mosaic all to himself? Because, George explains, he brings bread and wine to the altar for a blessing, and thus prefigures the Eucharist from the very first book of the Old Testament. Obvious, really.

Melchizedek? Who? A minor biblical character with bit part in Genesis Chapter 14, so why does he merit an enormous square footage of mosaic all to himself? Because, George explains, he brings bread and wine to the altar for a blessing, and thus prefigures the Eucharist from the very first book of the Old Testament. Obvious, really.

With the inexplicable explained, we now turn to the two Star Attractions of San Vitale, the gobsmacking mosaic panels representing (to the left) the Emperor Justinian and his retinue, and (to the right) the Empress Theodora and her retinue. The term awesome is much over-used and devalued, but if you want to know what it really means, go to Ravenna and gaze in wonder at these panels.

I’d like to take up the rest of this blog post just going on and on about these two mosaics in this one church, but anything I say has already been said much more authoritatively elsewhere, so I will put some links at the end of this post for readers’ further study.

In any case, we have only just started on our tour. We’re here for three days of serious study. One World Heritage site done, seven to go.

Mausoleum of Galla Placidia

The Mausoleum of Galla Placidia is another bare-brown-brick building, small and apparently insignificant, next-door to San Vitale. Our group learns from George to think of it as the so-called Mausoleum, because Galla Placidia (392-450, a wise and powerful Roman Empress), in fact died and was laid to rest in Rome and not in Ravenna.

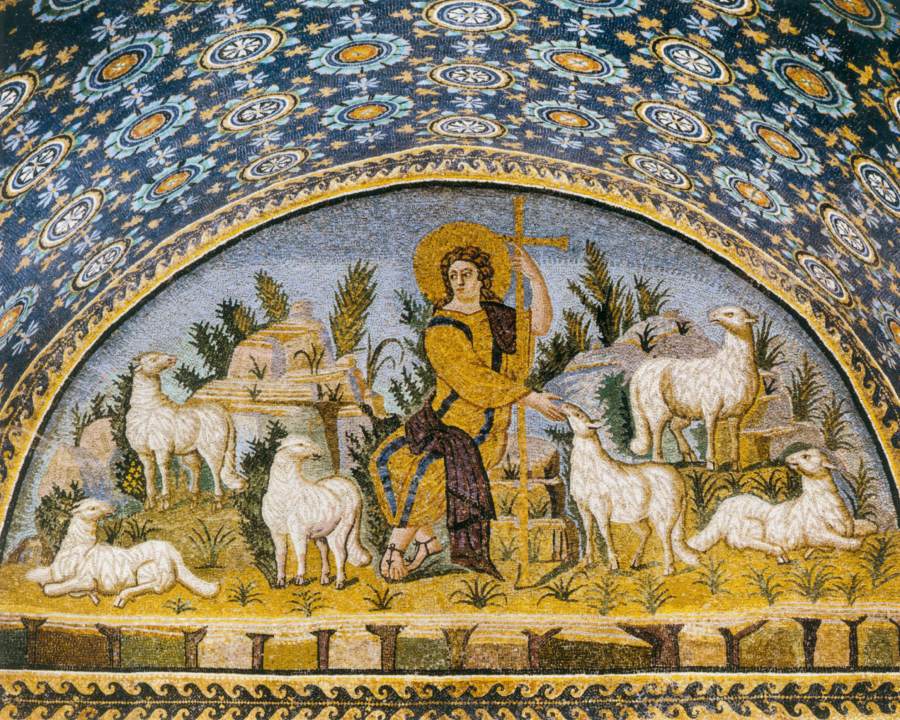

Whatever the actual purpose of the building, once inside it, when your eyes accustom to the low light level, you find yourself in possibly the most wildly colourful and blingy interior imaginable. Dark Ages? Forget it. Ceilings of stars, an arch of fruit and veg, Christ the Good Shepherd with his sheep, Saint Lawrence about to be roasted on a griddle, doves on a fountain, oxen drinking from a pool. On the domed ceiling around the Cross, the four evangelists in their avatar forms: the Angel for Saint Matthew, the Lion for Saint Mark, the Ox for Saint Luke and the Eagle for Saint John. It’s a riot.

Neonian Baptistry

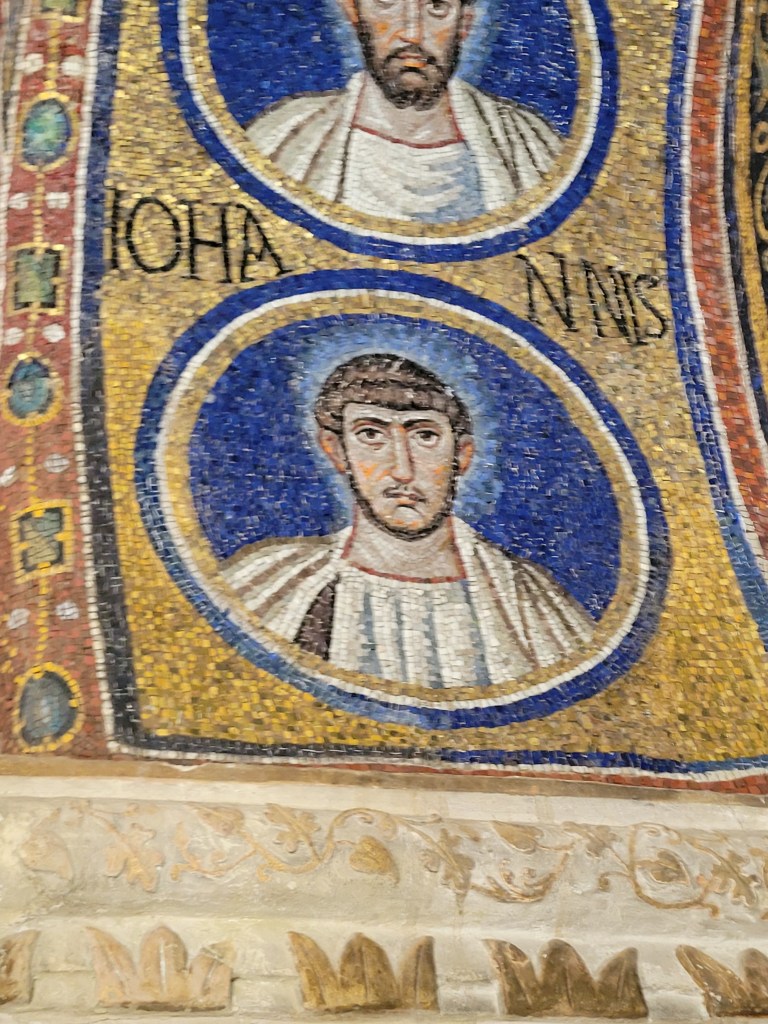

The Orthodox Baptistry, completed by Bishop Neon by the end of the 5th century, is a tiny unadorned brick octagon with (once again) big surprises inside. Colourful mosaic patterns and inscriptions around the arcading, prophets in the spandrels, bas-relief stucco figures in the clerestory, all surmounted by a stupendous domed ceiling featuring the twelve apostles surrounding Christ baptised by John the Baptist in the River Jordan. In the centre of the floor, a massive but later marble baptismal font. The ceiling mosaic was apparently heavily restored in the 19th century, and the Byzantine decoration in the niches has been replaced in the Renaissance period with intricate pietra dura marble panelling.

Basilica of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo

A huge, bright, rectangular space with side aisles, which has undergone many changes over its 1,500 years, from an early conversion from the Arian persuasion of Theodoric to the orthodoxy of Justinian, right up until the destruction of the apse by Allied bombing in World War II. Many mosaics have been lost, but what remains are two astounding and immensely long lateral mosaics stretching the full length of the nave above the arcades of columns to the aisles, and continuing through the clerestory to the level of the roof.

On one side, a procession of 22 female saints leaving the city of Classe (the port of Ravenna) to follow the Magi to worship the Virgin and Child flanked by four female angels. On the other side, a procession of 26 male saints leaving Theodoric’s palace in Ravenna to worship the enthroned Christ flanked by four male angels.

On one side, a procession of 22 female saints leaving the city of Classe (the port of Ravenna) to follow the Magi to worship the Virgin and Child flanked by four female angels. On the other side, a procession of 26 male saints leaving Theodoric’s palace in Ravenna to worship the enthroned Christ flanked by four male angels.

On the wall at the west end of the church, a small mosaic panel labelled IUSTINIAN, which probably originally commemorated Theodoric but was repurposed early on when the Byzantine emperor replaced the Ostrogoth king.

Arian Baptistry

With close similarities to the Neonian Baptistry, this is another small octagonal building, which stands in a quiet paved square accessed through a narrow side street. It was built for the baptism of Arian Christians, who appear to have carried on living side by side with the Byzantine Orthodox Christians for some time after the arrival of Belisarius and his army.

Fewer mosaics survive here – just a marvellous domed ceiling featuring a circle of Apostles around a central scene of a naked Jesus hip-deep in the River Jordan, being baptised by John the Baptist, overlooked by the white-haired personification of the river.

Archiepiscopal Chapel

The Archbishop’s Palace is beside the (mostly rococo) Cathedral of Ravenna, a huge baroque palazzo divided between the offices of the curia and a museum full of carved stone fragments, liturgical artefacts and other bits and pieces including the 6th century ivory throne of Archbishop Maximianus. The throne by itself would make a visit to Ravenna worthwhile, a marvel of intricately carved panels, the manufacture of which must have required the sacrifice of innumerable elephants.

Wandering around the museum’s second floor you suddenly realise that the building’s origins are perhaps not quite so baroque as they appear to be. With no advance warning, you pass from palely-decorated archiepiscopal apartments through an innocuous doorway, and you instantly hurtle back one-and-a-half millennia. You find yourself in a tiny anteroom adjacent to a slightly less tiny cruciform chapel. From the time-travel point of view, it’s a bit like the TARDIS, but smaller on the inside. And the other main difference is that both the anteroom and the chapel are lined with spectacular 6th century mosaics. Actually, it isn’t like the TARDIS at all.

I can’t even try to describe the mosaics, so I’ll merely show you some photos. You really do need to travel to Ravenna and look for yourselves.

After our course finished, Frances and I stayed on in Ravenna for an extra day, and the Archiepiscopal Chapel was one of the places we chose for a second visit. Oddly, the transition from Baroque to Byzantine was just as much of a shock the second time as the first time.

Basilica of Sant’Apollinare in Classe

Classe or Classis is the port of Ravenna, a 20-minute ride by bus from a bus stop beside the train station. It appeared to us as a fairly featureless place and we didn’t note anything resembling a town centre, but there, in amongst some very ordinary mid-20th century suburban housing, was a tall cylindrical belltower beside a large basilica church, similar in size and layout to its namesake church in central Ravenna. In the Ravenna church, the surviving mosaics are at a high level above the nave arcading. In the Classe church, the big feature is the huge half-domed apse and the wall above.

In the apse, Saint Appolinaris against a green wooded landscape accompanied by a flock of very tall sheep, beneath a large cross in a blue circle. On the wall above, a haloed bearded Christ in a roundel, flanked by the Apostles in their symbolic forms. And more very tall sheep. Impressive, but slightly strange.

Mausoleum of Theodoric

Having seen and marvelled at the main mosaic sites, we take a short walk beyond the Ravenna train station to see the Mausoleum which King Theodoric built in 520 as his future tomb: a stumpy two-story decagonal building surmounted by a monstrous circular limestone slab, which has been calculated as weighing some 230 tons. Impossible to imagine how the Ostrogoths of the 6th century could have lifted it onto to the top of the building, but if you think that Brutalism was invented in 1950s Eastern Europe, think again.

The upper chamber of this structure is where Theodoric was buried in 526. We reach it via a modern external staircase. It is a remarkable space but plain and unadorned within – although one suspects that it might have been lined with mosaics in its early years. In the centre, a massive porphyry sarcophagus in which Theodoric was laid to rest. Alas, he didn’t rest in peace for very long. When Belisarius arrived in 540 and claimed Ravenna on behalf of the Orthodox Emperor Justinian, the Arian Christian Theodoric’s remains were unceremoniously disinterred from the sarcophagus and his bones scattered.

And there’s more …

Eight stunning buildings seen and discussed in three days. Thanks to George, we can begin to understand and appreciate them and the mosaics within them: their history, their iconography, and some technical aspects of construction and decoration. But that’s not all, because we have some additional visits to sites which aren’t on the UNESCO World Heritage List.

House of Stone Carpets

The Domus dei Tapetti di Pietra is an archaeological museum in central Ravenna approached through the rear of the Church of Sant’Eufemia. Here, the mosaic floors of a complex of late-Roman and Byzantine buildings are preserved and displayed in situ. You can view them from platforms and walkways. The floor mosaics are big and impressive, but their colouring is neutral and they comprise mostly geometrical patterns with only minor figural components.

Interesting that they are referred to as stone carpets, because many of their designs closely resemble those of traditional knotted woollen pile carpets which have been made in the Middle East for the past couple of thousand years and which are still being made today. I wonder which came first – stone carpets or pile carpets?

Church of San Giovanni Evangelista

A big city centre church originally built in the 5th century by Galla Placidia. Almost all of its mosaics were stripped out in the 18th century, and then, to add insult to injury, the church was heavily damaged in an Allied bombing raid in World War II. It was subsequently rebuilt but few of its original features remain.

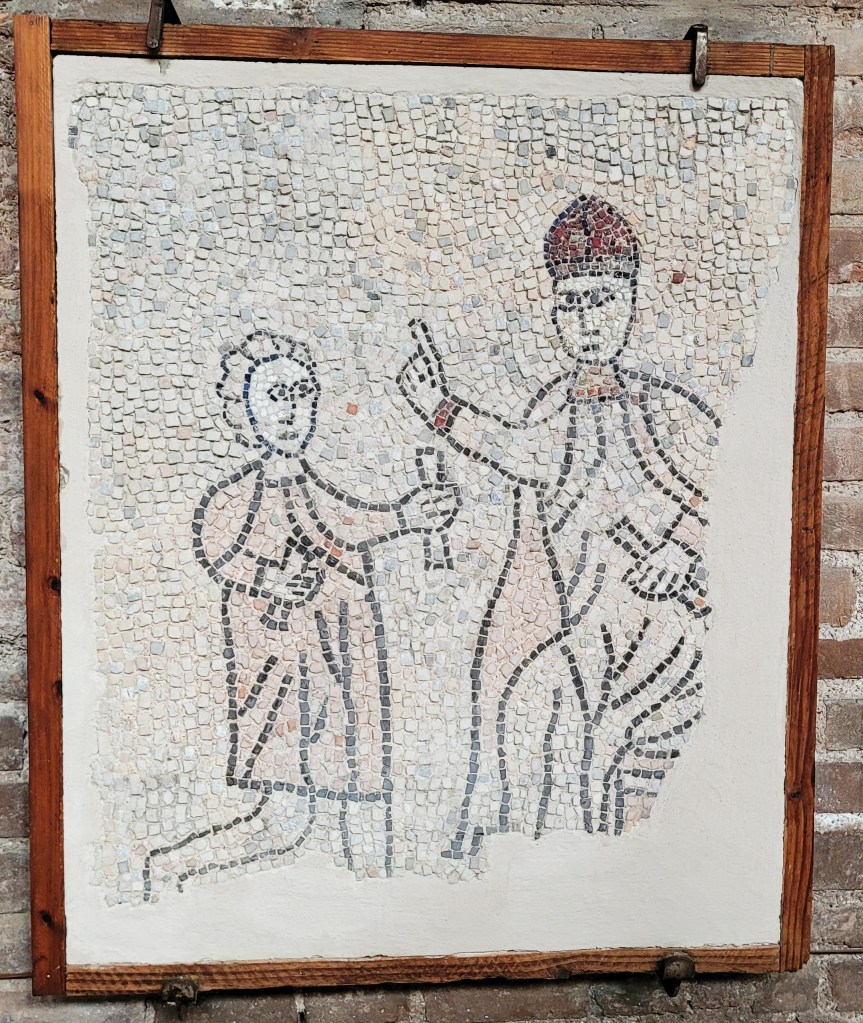

The main items of interest are some fragments of floor mosaic which were discovered during the rebuilding process, and which have been preserved and displayed in frames on the lower walls. These mosaics were created in the early 13th century and since they are five or six hundred years more recent than the early Ostrogoth and Byzantine mosaics and the other sites, you might expect them to be even more spectacular and sophisticated than the earlier productions.

But no. By comparison, they are extraordinarily crude and naïve. A bestiary of real and mythical animals; angels and mermaids; historical narrative scenes from the Fourth Crusade: we can see Pope Innocent III calling the crusade in 1202; troops of soldiers; ships; the surrender of Constantinople. It’s all utterly charming and to our eyes cartoonishly mad, but we have to presume that since these mosaics made up a church floor, they were made for viewing with a serious theme and purpose.

Our group has a brief discussion: do these simple, childish mosaics signify:

- that the ancient art of making beautiful colourful mosaics has been lost in these later centuries of the Dark Ages, or

- that by the 13th century Ravenna is a sleepy provincial town whose church-builders are not rich enough to employ top-class mosaicists, or

- a combination of the above, or

- some other reason.

Our considered conclusion: we don’t know.

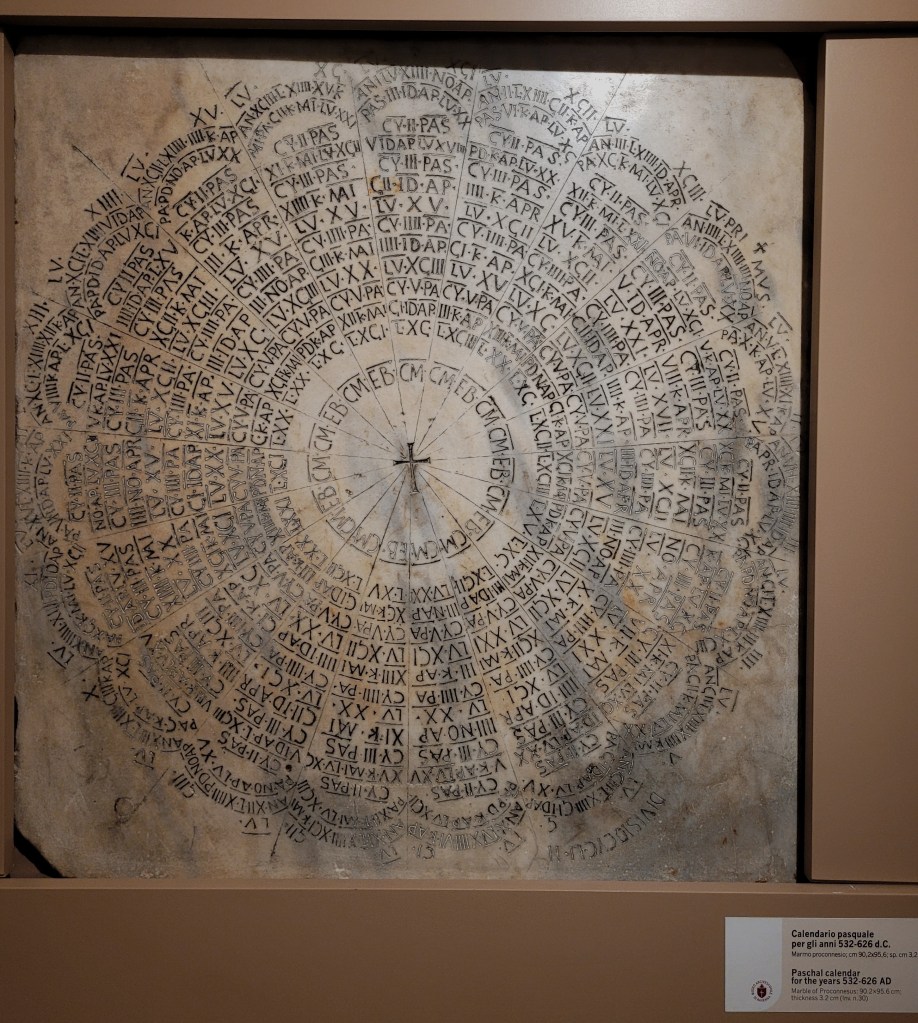

Classe Museum

While in Classe to visit the Basilica of Sant’Apollinare, we call in at Classis Ravenna – Museo della Città e del Territorio, a 19th century sugar factory recently re-purposed into a historical museum for Ravenna and the local area. Outside, a long shallow flight of steps up to the entrance featuring a fabulous modern mosaic river with waterfall. Inside, a bright, spacious interior with well-labelled displays of Roman and Byzantine artefacts, stone fragments and mosaics.

Some pieces on display are reproductions, and we have previously seen their originals at other Ravenna sites. The museum is clean and new and educational and quite interesting, but you get a feeling that they have rather more space than they know how to fill. And you find yourself wondering why they have spent so much time and energy making museum displays representing objects and buildings which survive in their entirety and can be viewed nearby.

Take-aways

Several times over the three days of our study tour, George asks us as a group which is our favourite building out of all the mosaic-lined wonders that we have seen so far. Our invariable answers: either this one’s our favourite or all of them are our favourite. You think you have seen the best of the mosaics and then you see one which is even more arresting, even more sparkling, even more miraculous.

For me, the firm favourite was San Vitale. Or perhaps it was the so-called Mausoleum of Galla Placidia. No, no, it was definitely the ante-room to the Archiepiscopal chapel. Or was it? Forget it. Who needs favourites anyway?

I’m writing these last paragraphs several weeks after the end of our visit to Ravenna. I didn’t take any notes and so am relying upon my memory – perhaps not such a good idea at my advanced age. And so, at the end of the three days, what did I come away with?

- A memory of a charming, civilised, laid-back city in mostly lovely late-spring weather;

- Admiration and respect for our approachable and knowledgeable tutor George, who ran the course with erudition, charm and painstaking attention to detail;

- Very warm feelings towards the other members of our delightful group, and towards the Courtauld team who organise the programme of short courses and study tours;

- Less warm feelings towards my school history and classics teachers (now all doubtless long dead), who insisted that nothing from The Dark Ages was worthy of study. Wrong!

- A sense of personal inadequacy from the realisation that although I now understand just a little about Byzantine mosaics, I’m ill-equipped intellectually and culturally ever to understand a lot about them;

- A degree of anxiety that when it comes to Art History there’s still so much to see and so much to learn but (at age 75) not too much time left for seeing and learning;

- Frustration with my deteriorating eyesight, which, the National Health Service informs me, is not amenable to improvement. I can only imagine how much greater my appreciation of the Ravenna mosaics might have been if I had been able to look upon them with unimpaired vision;

- Lasting impressions (and a phone-full of photos) of a group of utterly remarkable buildings lined with utterly amazing mosaics.

And finally, as ever with Courtauld Institute Art History courses, a sense of wonder and awe at the extraordinary ability of human beings (in whatever age) to create and communicate beauty through art.

Further reading: the Justinian and Theodora mosaics in the Church of San Vitale

Andreescu-Treadgold, Irina, and Warren Treadgold, “Procopius and the imperial panels of San Vitale”, Art Bulletin 79 (1997), pp. 710-23.

Barber, Charles “The imperial panels at San Vitale: a reconsideration”, Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies 14 (1990), 19-42.

James, Liz, “Global or Local? The Mosaic Panels of Justinian and Theodora S Vitale, Ravenna”, in Global Byzantium: Papers from the Fiftieth Spring Symposium of Byzantine Studies, ed. by L. Brubaker, R. Darley, and D. Reynolds (London, 2020).

Sarris, Peter, Justinian: Emperor, Soldier, Saint (London, 2023).

“Dress Styles in the Mosaics of San Vitale”, at: https://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2012/byzantium-and-islam/blog/topical-essays/posts/san-vitale

A useful basic video available here

Grateful thanks from your legion of faithful readers who have been in need of a Random Treasure top up. And your jaunt to Ravenna certainly filled that bill. Mark and I were there some years ago and it was wonderful to have the highlights recalled. The 6thCE was not a fun time to be around Ravenna. The Justinianic Plague of mid century (also reported on by Procopius) and widespread social disruption because of climate linked crop failures very nearly put paid to everything. I side with Gibbon’s view that adopting christianity was the poison pill for the Empire but have to admit that the art it produced is ravishing.

LikeLiked by 1 person