The Dark Ages

I’m ashamed. I had always thought of myself as well-rounded in History, possessing a pretty thorough overview of what went on (albeit mostly in the West) from classical times right up until my own times. But how wrong I was!

At my English grammar school, founded in 1792, teachers of classical subjects tried to teach me about ancient Greeks and Romans. Their pedagogical efforts were doubtless greatly influenced by their own classical education, which would have been largely reliant upon the writings of Edward Gibbon in his great work The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, published in six volumes between 1776 and 1789.

At my English grammar school, founded in 1792, teachers of classical subjects tried to teach me about ancient Greeks and Romans. Their pedagogical efforts were doubtless greatly influenced by their own classical education, which would have been largely reliant upon the writings of Edward Gibbon in his great work The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, published in six volumes between 1776 and 1789.

Under Gibbon’s interpretation, the Roman Empire fell apart on the removal of its headquarters from Rome to Byzantium/Constantinople in the 4th Century AD or CE. Thereafter, history fizzled out for the next several centuries. Not much happened. It was The Dark Ages. Nothing to see here. Let’s move on into more interesting times.

Then my school history teachers took over. For them, history belonged almost exclusively to the British, and overwhelmingly to the British Empire. As did everything else. The curriculum took a quick romp through the Saxons and Vikings and Normans and their formative role in the building of The British Character. Then Dr Derry and Mr Blakeway led us on a direct route through the Plantagenets, Tudors, Stuarts, Hanoverians and Saxe-Coburgs, mostly characterised by monarchs and prime ministers and generals victorious in battles and wars against Johnny Foreigner all along the way.

History then finished, perhaps around the time of the Entente Cordiale (1904). Everything after that was too recent to be counted as history. You need to be aware that when I was at school, in the 1950s and 1960s, most of my teachers had personally taken part in the Second World War. The Headmaster had won a Military Cross and lost a leg. The Head of History had done something top-secret in Norway. A few were in the First World War. Dr Stanton (Classics) and Dr Freudenburger (Chemistry) fought on opposite sides in the Battle of the Somme.

History then finished, perhaps around the time of the Entente Cordiale (1904). Everything after that was too recent to be counted as history. You need to be aware that when I was at school, in the 1950s and 1960s, most of my teachers had personally taken part in the Second World War. The Headmaster had won a Military Cross and lost a leg. The Head of History had done something top-secret in Norway. A few were in the First World War. Dr Stanton (Classics) and Dr Freudenburger (Chemistry) fought on opposite sides in the Battle of the Somme.

As a result, my teachers didn’t think that their lived experiences had become History quite yet, so the 20th century wasn’t in the history syllabus. It was current affairs.

I subsequently filled in some 20th century historical ignorance by studying modern history in the first year at University. But at the earlier end, what happened between, say, 400 and 1300 AD, remained just a fuzzy image. And no image at all when it came to history outwith the British Isles. To me, The Dark Ages were not merely Dark, they were Blank.

Until, that is, a few weeks ago, when my view of The Dark Ages burst into unbelievably brilliant sparkling gorgeous colour in Ravenna.

Ravenna

Frances and I were in Ravenna for a three-day study tour organised by the Courtauld Institute of Art. The course title: Ravenna: Capital of the Mosaic.

If you haven’t visited Ravenna, it’s a city of about 150,000 people, located around 5 miles (8 km) inland from the Adriatic coast of Italy, and some 90 miles (150 km) south of Venice. The city centre is charming and compact, and you can stroll between almost all of the main cultural attractions within ten or fifteen minutes.

We can see that we’re in an old city, but it doesn’t present itself to the world as a tarted-up ostentatious kind of place, replete with palaces and grand churches and monuments and stately boulevards. Most streets are narrow, lined with buildings of almost any age or period, with yellow and buff-coloured stuccoed walls and terra cotta pantiled roofs. Paved squares feature solid-looking palazzi alongside bland modern office buildings and hotels. You suspect that many houses have lovely courtyard gardens hidden behind their high walls, but a flaneur in central Ravenna sees few trees and little greenery.

There are streets of small shops selling upmarket designer clothing, jewellery and gifts; delis, patisseries and cafes, but not many cheap trashy gift shops of the kind that tend to dominate in other tourist centres. It seems a prosperous, relaxed, laid-back city, with very few beggars and little poverty in evidence. The streets are clean, well-swept, and despite the many dogs promenading with their owners, there’s little or no evidence of abandoned poop.

Of course the casual visitor who’s in a place for only a few days can’t get a real picture of what life is like for residents. For all I know, Ravenna might be beset with social problems and poverty. But if so, it’s unusually good at concealing them.

The streets are busy here in early May, but almost everyone is speaking Italian. From the very large number of primary-school-age children and teenagers parading in noisy, cheerful troops through the streets, it’s clear that Ravenna is an important venue for school visits. Presumably a field trip to see the Ravenna mosaics (and also Dante’s tomb) is a standard feature in the school history curriculum – in just the same way that children in our Scottish schools are almost inevitably taken for an overnight visit to York.

And the weather is lovely. Mostly sunny and warm, but it’s still springtime and it doesn’t get unbearably hot. So we’re all set up for three days of intensive Art History.

Have I portrayed Ravenna as an anaemic sort of place with nothing much to see? Kindly remind me why we are here. Ah, now, here’s the first stop on our study tour – a rather featureless bare brown brick octagonal church, with solid buttresses and small, dull windows. I wonder what’s inside?

Our group enters the Church of San Vitale and – BAM! KAPOW! Do you remember the first time you saw that thrilling moment in The Wizard of Oz when Dorothy’s cabin, hurled by a tornado from Kansas, crash-lands in Munchkinland? Dorothy and Toto go to the door, open it and – gasp! – monochrome switches into Glorious Technicolor?

You get a similar sensation on entering San Vitale, but here, it’s an idea that the builders had 1,500 years before MGM played the same trick in Hollywood in 1939. It’s goodbye Dark Ages, hello eye-popping colour!

Some description and images of the interior of the church will follow, but not yet, Random Treasure blog readers, not yet. I’m sorry, but first there’s some homework.

Our course leader and tutor George has given us a few hefty chunks of intensive pre-course reading, so by the time we arrive in Ravenna, we already have a vague notion that what we’ll be looking at is just a sliver of history between around 450 and 600, when this small city became, for a short time, Dark Ages Central.

I won’t force you to read the dense academic papers which we were encouraged to absorb. I’ll try to give you the gist.

Ostrogoths and Byzantines

First, some historical background. In the context of Ravenna, when we talk about history, we’re taking the long view. The building of the church of San Vitale was started in the year 526 and completed by 547. So it has been there, substantially unaltered, for 1,477 years. Here in the United Kingdom we think of ourselves as living in an old country abounding with neolithic remains, Roman forts, mediaeval cathedrals, castles and manor houses. But do we have a complete and highly-decorated building surviving from the 6th century? No, I don’t think so.

Summary: under the Ostrogoths, Ravenna was declared the capital city of the Arian Christian kingdom of Italy, and then, under the Byzantines, it became the capital city of the Orthodox Christian Exarchate of the Western Roman Empire. That’s simple enough. Got it? Need I elaborate?

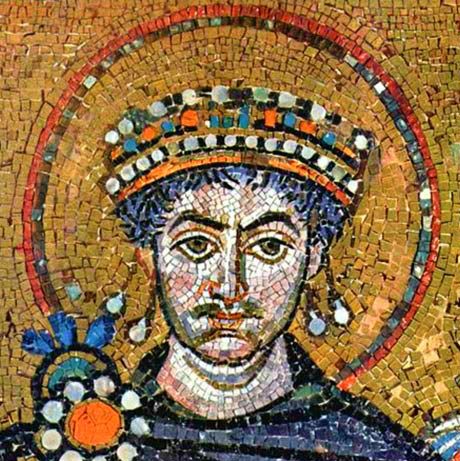

To get what’s going on in Ravenna – or, more precisely, what was going on there in the fifth and sixth centuries – you need particularly to know about three historical figures: King Theodoric (454-526), Emperor Justinian (482-565) and Empress Theodora (c.490-548).

Three fascinating larger-than-life characters. Look them up. Theodoric, upstart Germanic leader of the Ostrogoths, rampaged westward with his army from Constantinople, conquering and pillaging all the way. Arriving at Ravenna, he finished off its Barbarian occupier Odoacer and set himself up in 493 as King of Italy.

In his three decades of Ravenna-based power, Theodoric built several of the mosaic-decorated edifices that our peaceable group of art history buffs is here to view. After his death, his Ostrogothic kingdom fell apart and the next occupier of Ravenna was the Byzantine army, which arrived in 540, led by the fearsome Belisarius, the Emperor Justinian’s top general.

Justinian and his wife Theodora were the ultimate power couple. He was a soldier, conqueror, judicial reformer, theologian and builder of churches and palaces. She was his chief adviser, a former actress and prostitute who was subjected to one of the most vituperative hatchet-jobs ever penned, in the Secret History, a book written by a disaffected courtier called Procopius.

Justinian and his wife Theodora were the ultimate power couple. He was a soldier, conqueror, judicial reformer, theologian and builder of churches and palaces. She was his chief adviser, a former actress and prostitute who was subjected to one of the most vituperative hatchet-jobs ever penned, in the Secret History, a book written by a disaffected courtier called Procopius.

Although Justinian and Theodora adopted Ravenna as the capital of their Italian conquests, it seems that they never actually visited the city, being rather too busy ruling over their Eastern capital in Constantinople. But despite the fact that they were never here, their power, money and mania for building remain visible all over Ravenna even a millennium-and-a-half later.

And then the caravan moved on and Ravenna turned into a sleepy backwater in which the next several centuries of changing artistic taste didn’t have much of an impact. Whereas in busier, richer Italian cities the old-fashioned mosaics were demolished and replaced by Renaissance frescoes, paintings and sculptures, it didn’t happen much in Ravenna. And because no-one got around to destroying and superseding the mosaics, more of them survived here than almost anywhere else.

Arian and Orthodox

And now some theological background. Nobody said that a three-day Courtauld course in Ravenna would be easy. This is not my department at all, so I’ll try to explain something very complex in very simple terms. In so doing, I’m almost certain to get it entirely wrong, and have therefore prepared myself for sneers of derision from my Random Treasure blog readers.

As far as I can make out, Theodoric (Ostrogoth) observed the Arian Christian doctrine, while Justinian (Byzantine) favoured Orthodox Christianity. George explains to us that under Orthodox belief, the three components of the Holy Trinity have precisely equal spiritual status. The Arians, however, take into account the essential humanity of Jesus Christ, who, having been begotten, can’t logically have existed eternally. The Arians thus ascribe to Jesus a slightly secondary position somewhat below that of God and the Holy Spirit.

I think that’s it. But I might have picked it up completely wrong. Suffice to say that these differences in theological outlook were significant in the events leading to the Byzantines overcoming the Ostrogoths, and in the building and adaptation of places of worship in 5th and 6th century Ravenna.

Tesserae

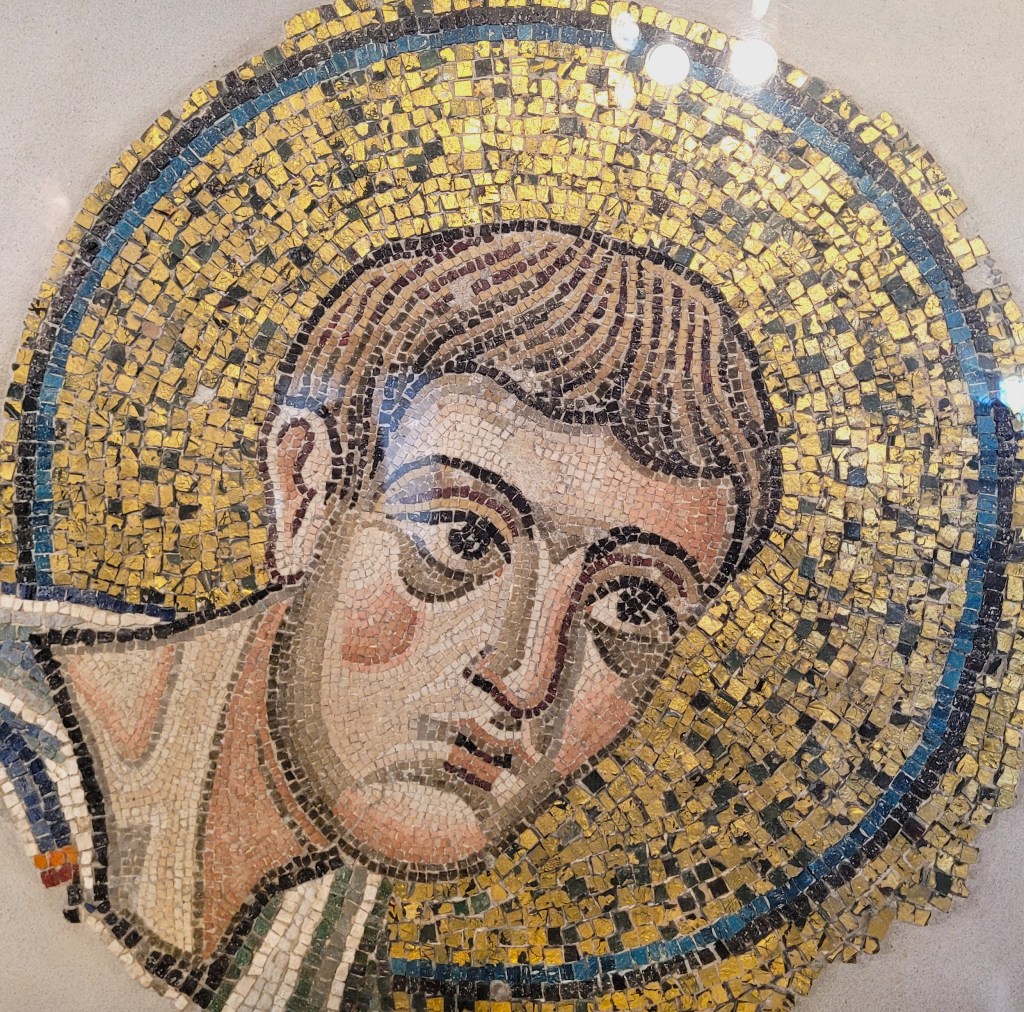

And finally, some technical background. The miniature tiles from which mosaics are made are called tesserae. Some of them are very tiny indeed. In the Archiepiscopal Museum there are some life-size portraits, surviving fragments from a vast 12th century mosaic in the apse of the old Cathedral of Ravenna which collapsed in 1743.

The fragments are behind glass, but you can get up very close and study the detail. The clothing and background are made up from brightly coloured glass tesserae, the largest perhaps 10-15 mm across. There’s lots of bright shiny gold and vibrant blue, with other colours used more sparingly. The faces and skin tones are not made from glass but appear to be tiny pieces of non-reflective marble or limestone, some just a few millimetres wide.

Mosaics are, of course, made to be viewed from a distance. Your average Ostrogoth or Byzantine churchgoer standing in the nave of the church wouldn’t get anywhere close to a mosaic lining the apse, or to the decorated frieze between the side aisle arcading and the clerestory. You wouldn’t see the individual tesserae. What you would see is a whole picture – just like you’d see on your television or computer screen today. But today we don’t call the tiles tesserae, we call them pixels.

You can spend a lifetime sudying the techniques and technicalities of Byzantine mosaics in the minutest details – which is what George does, which is why he’s our course leader and tutor. He tells us how the glass tiles were made and cut, and where they came from (mostly made in the Levant and imported into Italy and elsewhere by sea).

Scholars have estimated the quantity and weight of the tiles used in the Ravenna mosaics (millions and millions, tons and tons). They have studied how mosaics were constructed, often by two artisans working outward from a vertical centre line. They have worked out how the tiles were applied over a number of layers of wet plaster, and how many tiles could be fixed in a working session before the plaster became too dry for the tiles to adhere.

In some but not all mosaics where tiles have fallen off, underdrawings have been observed which sketch out the designs and colours to be followed by the artisans. Some instances have been noted where the workmen ran out of supplies of tiles of a particular colour of tile and filled in the spaces with paint. In some mosaics you can see where the workman on one side has spaced the tesserae out slightly more widely than the workman on the other side – which might not make much difference near the centre of the mosaic but can cause serious asymmetry at the outer edges.

Another thing about mosaics is that you can revise and update them. A bishop dies and is replaced by a new bishop, so you prise off the tesserae comprising the old bishop’s face and name label, and you replace them with the new bishop’s face and name. Or you could obliterate a figure and replace it with a mosaic curtain. Sometimes the obliteration doesn’t quite work and you leave a body part behind – perhaps a stray arm stretched out across a mosaic pillar as in the Basilica of Sant’Appolinare Nuovo.

There’s much more technical stuff that you can immerse yourself in. It’s all totally fascinating.

Personnel

We’re almost ready to start our study tour of Ravenna, but just before we set off, it’s necessary to introduce you to the participants.

There are 11 of us attending the course, plus George, our tutor. In the brief introductions at our first meeting, it turns out that other than George, Frances and I are the only ones who have been in Ravenna before. We were here on a day trip in the summer of 1980, which was before several of the members of our party were born. We also discover that despite our previous visit, we are perhaps the least well-equipped for the task at hand.

George is youthful and full of enthusiasm. He has fairly recently completed his PhD thesis about images of Christ inscribed with epithets in Middle and Late Byzantine art, which focuses on the relationship between images and text and how this sheds light on Byzantine Christian onomastics, social and devotional practices, and the perception of iconography. Despite which, he’s cheerful, down-to-earth, humorous and accessible, and very conscientious in shepherding our group from one amazing site to the next. George has taught on short courses at the Courtauld for a few years, but will be starting a regular gig as a lecturer in the autumn of this year.

A___ is a vivacious and decisive designer-clad Russian, resident in Geneva, with other homes in the Swiss Alps and in London. She’s a serial participant in Courtauld courses and we first met on the Van Eyck course in Brussels last year. So we know that she has a unique ability, with the aid of her smartphone, to navigate her way faultlessly, at a brisk pace, from whichever Art History site we might be visiting, to the nearest top-rated café or restaurant. We know that if we follow A____ everywhere, we’ll be well-set-up if somewhat breathless.

C____ has very recently retired from a London-based post as a senior in-house solicitor for a large multinational industrial firm. In a bid to keep himself fully occupied in the early months of his retirement, C____ has booked this course, immediately followed by another Courtauld study tour, plus courses in all four weeks of the Courtauld summer school in London, plus several trips over the rest of this year to far-flung destinations including (if memory serves correctly) Easter Island.

C____ is a senior corporate lawyer originally from South Africa but now resident in London. Affable and very much engaged in the course, but we don’t have much one-to-one conversation over our three days together in Ravenna, so I don’t find out much more about him.

D____ is from Dublin, a charming and urbane retired solicitor and a long-time student of Art History. Of all the group (excepting of course our leader George), she seems to be the best able to interpret the Christian iconography in the mosaics.

M____ is a delightful young Russian resident in London who works in the arts as a digital marketing executive, and seems to have a very strong foundation in Art History. After the course in Ravenna, she’ll be travelling to meet her husband in Ibiza, where their boat is moored. They plan to sail on from there to the Greek islands. M____ teams up with Anna to march us briskly between historic sites and well-reviewed eateries.

N___ and S____, a retired married couple from London. I don’t have much conversation with N___, but she’s clearly comfortable looking at Byzantine mosaics in a way that I’m not. S____ worked in financial systems development and claims to have little or no interest in Art History in general and Byzantine mosaics in particular. However, he’s a keen photographer, and is here to accompany his wife and to take photos for his own interest and pleasure.

S____, from Beijing but resident in London, is in process of completing a postgraduate Art History degree course at the Courtauld, so she’s well-prepared to appreciate all the art that she is going to see on our tour. She’s here accompanying A___, whom she met on a previous course.

V_______ was a charity fundraiser and event organiser until her retirement two or three years ago – when she courageously embarked on the intensive full-time postgraduate Art History course at the Courtauld, and survived to tell the tale.

And then there’s Frances and me, by some margin the eldest members of the group, and with probably the least convincing credentials for appreciating the niceties and abstrusenesses of Ostrogothic and Byzantine mosaics. Unlike some of our fellows we don’t have postgraduate art history degrees or equivalent qualifications. And as a lapsed Episcopalian and a lapsed Jew, each with an entirely secular outlook, we don’t have what some of the group have – the bonus of a Roman Catholic or a Russian Orthodox upbringing which has hard-wired into them a deep understanding of Christian iconography.

In fact, for us, the prospect of the next few days is a little daunting.

Are we daunted? Not too much. We’re up for it 😀.

So. You know why we’re here. You have been introduced to Ravenna. You’ve done the homework and have met your fellow students. It’s finally time to get on our way …

Read about the amazing places we visited in Mosaic, Part 2.

I await the next instalment with bated breath…….

LikeLike