Why we were there

There are thirteen of us, almost all previously unknown to one another. Thirteen souls from across the world, assembled closely together for three days of single-minded focus upon a common but arcane objective, three days of deep emotional and intellectual immersion. Ooohh, what’s this about? Is someone gonna die? Is it a murder mystery? Is it about a cult? Is it a reality TV show? Will there be a detective?

No, no, it’s much more serious than any of the above. It’s an Art History study tour. Two or three times in recent years, Frances and I have attended summer school programmes organised by the Courtauld Institute of Art, one of the foremost institutions in the world for the study of art history (https://courtauld.ac.uk/short-courses-2023/summer-school/). Generally these courses take place in the Institute’s premises in London, and since the covid pandemic, some have been offered online. But there’s also a small programme of overseas study tours, and this year we decided to treat ourselves. Off we went to Belgium.

No, no, it’s much more serious than any of the above. It’s an Art History study tour. Two or three times in recent years, Frances and I have attended summer school programmes organised by the Courtauld Institute of Art, one of the foremost institutions in the world for the study of art history (https://courtauld.ac.uk/short-courses-2023/summer-school/). Generally these courses take place in the Institute’s premises in London, and since the covid pandemic, some have been offered online. But there’s also a small programme of overseas study tours, and this year we decided to treat ourselves. Off we went to Belgium.

Twelve bright-eyed students led by our lecturer and course leader, Dr Susan Jones, who is young, British, brilliant, very well-organised, and an excellent communicator, replete with more knowledge about her subject than anyone else anywhere ever.

The students: nine women, three men. Nationalities include English, Scottish, Russian, Dutch, Spanish, American. Places of residence include London, Edinburgh, Geneva, Los Angeles, Madrid. The Russian is from Switzerland. One of the English lives in Spain. The Spaniard lives in England, as does the Dutchman and one of the Americans. We’re an international bunch, ranging in age from 30s to 70s. The wrinklies of the party: a couple from Edinburgh. That would be Frances and me.

Here we are, gathered in Brussels to study early Netherlandish art. Not here merely to look at nice pictures. Oh no, this is brainy stuff. Here’s part of the course description:

Netherlandish painters were (and are) famed for their ability to capture nature through near-miraculous interactions of the eye, mind and hand, representing the tiniest details of things with such control of the pen or brush that it is genuinely astonishing. Their paintings, manuscript illuminations and drawings are often discussed in the light of rhetorical ideas about imitatio, classifying their activity as no more than imitation. On this tour, however, we shall think about more than observational skills. Through careful analysis of a series of famous works dating between c.1420 and c.1650, we shall reconsider contemporary ideas about creation, and what we would call ‘creativity’… We shall ponder … the notion of ingenium – a kind of skill which cannot be learned but which is innate, and which is one of the bases for the modern idea of genius…

What we did

Day One, morning. We start with a lecture at KIK-IRPA, the Belgian Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage (https://www.kikirpa.be/en/). This august government institution records, studies and preserves Belgium’s cultural and artistic heritage. In their comfortable lecture theatre our course leader Susan introduces us to some of the concepts that she wants us to get our heads around over the next three days. Some of us (i.e. me) are more confused than others.

Day One, afternoon. A visit to the Old Masters section of the Royal Museum of Fine Arts in Brussels city centre (https://fine-arts-museum.be/en) to look at paintings and to see if we can apply some of this morning’s theoretical concepts to this afternoon’s art objects. How much of the incredible detail in their paintings did our early Netherlandish painters copy directly from life, and how much came from their imagination? Were they merely craftsmen copying conventional images, or did they add their own creativity, imagination and ingenuity to the assemblage of religious characters, commissioning clients, events, symbols, buildings and landscapes depicted in their paintings? Draftsmen or artists? Simple mediaeval technicians and copyists or sophisticated, enlightened Renaissance thinkers?

It was hard. Fortunately, if it was too hard to try to understand, there was still the reward of looking at room after room of stunning pictures. Rogier van der Weyden, Hans Memling, Dirk Bouts, Pieter Bruegel (and other members of his family), Hieronymus Bosch. These extraordinary artists tend to be slightly more obscure and much less well-documented than their Italian Renaissance contemporaries. They didn’t have a Vasari to provide them with admiring biographies. Some art historians (mercifully not including Dr Susan Jones) still call these painters Flemish Primitives. But just look at their pictures. Could anything be less primitive?

Day two, morning. Train from Brussels Centraal Station to the charming town of Ghent. A walk through the park to the Museum of Fine Arts (https://www.mskgent.be/en), where you stand looking through a huge glass wall into a workshop. Within, a team of experts from KIK-IRPA have recently started on a three-year project to clean and restore the upper panels of the Van Eyck brothers’ Ghent Altarpiece. The panels not currently being treated are standing on easels just on the other side of the glass.

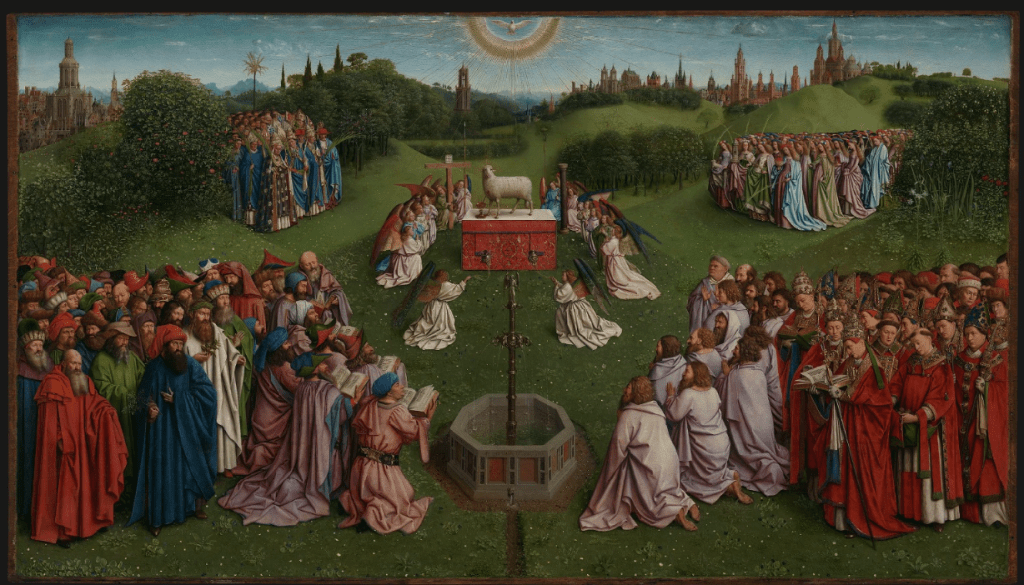

Your jaw drops. You might have spent hours looking at online images of the Ghent Altarpiece (look here: http://closertovaneyck.kikirpa.be/), but nothing prepares you for seeing the real thing about two feet away from you through a sheet of crystal clear glass.

Susan tells us about the Altarpiece. Which bits were painted by Hubert before his early death and which by Jan? Was Jan being falsely modest when he described himself in an inscription on the painting as “second in art” to his deceased brother? How much have the images been altered by repeated restoration and overpainting since 1432 when the work was completed? Why does God have one crown on his head and another at his feet? Are Adam and Eve modelled on real people? What music are the heavenly orchestra playing and the heavenly choir singing (answer: here)? What exactly are the restorers doing so intently?

The boss restorer sees us gazing through the glass. Normally she would ignore the thousands of viewers peering into the studio – but we’re different, because we have Susan leading us. Griet Steyaert comes out to say hello, greets Susan with a kiss on each cheek, and spends several minutes explaining to our party what’s going on in the workshop. It’s a very early stage in the restoration programme. Many layers of varnish are being carefully stripped off the panels. Take a cotton bud, only a little bigger than the kind that you stick into babies’ orifices. Dip it in a special solvent. Rub it in a circular motion over a small section of your panel (in this case God’s right knee). Repeat a billion times. Report your findings to the International Committee so that they can decide what you should do next. Yes, they are rubbing solvents on (perhaps) one of the ten most important artworks in the Western canon. It’s a serious business, not to be taken lightly. We’re mesmerised.

From there we move on to St Bavo’s Cathedral, where we see the Altarpiece in situ, again through glass, from a few metres away. They don’t let you get nearer. The lower panels quite recently re-installed following the first stage of the restoration project, the upper panels temporarily replaced by convincing colour photographs while the real ones are being restored in the Fine Arts Museum. Susan tells us fascinating stuff about the symbolism, the brush-strokes, the theft and partial recovery of one of the panels, the inscriptions.

It’s a marvel, but a slightly surprising marvel. The Mystic Lamb stands on the altar, as expected, the central element of the central panel of the composition. It’s what gives the altarpiece its name and fame, the thing we’re all here to see. There’s no doubt about the Lamb’s focal importance because of the crowds of people, kings, prophets, angels, saints, knights, pilgrims and bishops shown flocking towards it in the lower panels. You expect it to be a life-size Lamb. Bigger, even. But it’s tiny, almost ludicrously small in relation to its significance. This is a bit of a shock. If you have obtained your prior knowledge of this artwork from disjointed online close-up images of the various Altarpiece panels, you expect the Lamb to be a big and prominent feature. It is the centrepiece of the whole vast assemblage of images. But it’s tiny. Puzzling.

I risk asking Susan a question which I hope sounds vaguely intelligent: why did Van Eyck choose to show, in the middle of his Altarpiece, a sacrificial lamb as Christ’s symbolical substitute? Why not give us a straightforward depiction of Christ Himself? No-one knows. Sorry.

We’re there in front of the Altarpiece for nearly an hour, during which time hundreds of tourists drift in and out of the specially-built viewing gallery. None stays for more than a few minutes; many merely take photos and selfies before moving on. But as for our group – we’re not tourists. We are Art History students. This privileged status entitles us to stand motionless, noses to the glass, gazing. Heedlessly, we stand in everyone else’s way, perhaps (for them) quite annoyingly.

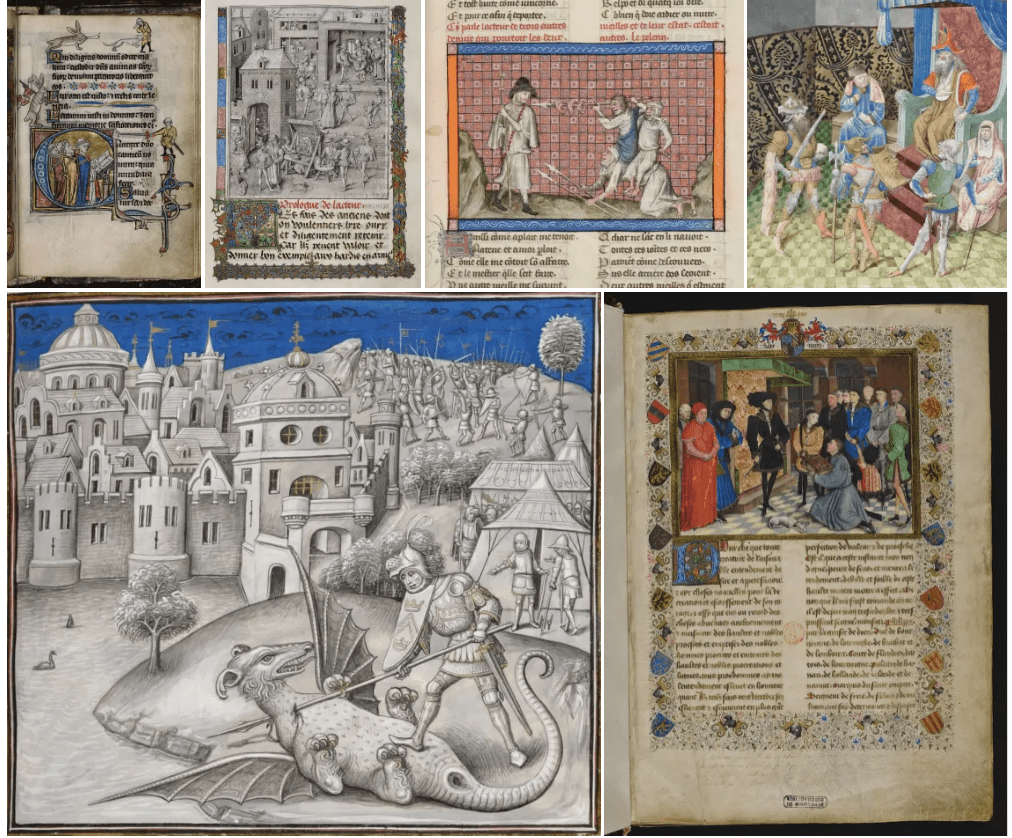

Day Two, afternoon. Back to Brussels for a session in KBR, the Royal Library, (https://www.kbr.be/en/) where we pass two blissful hours with Daan van Heesch, Head of Prints and Drawings, and Joris van Grieken, Curator of Prints and Drawings. From their collection of more than one million graphic objects, they have carefully selected ten drawings to show us and to explicate to us in detail. This is intensive. So I’ll just pick two.

Landscape with a fisherman and a watermill by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, signed and dated 1554. A huge tree overhanging the waterside, a mill with a large waterwheel, a bored-looking fisherman, a rowing boat with a boatman tending floating baskets, a horse drinking from the river, its rider tipping dangerously forward, more houses and pedestrians in the far distance. The longer you look, the more you see. You can get lost in it.

Two peasants seen from behind by Roelant Savery (previously attributed to Pieter Bruegel the Elder). A simple drawing of, yes, two peasants seen from behind, from a series of drawings of enormous significance to historians of Netherlandish art. At the bottom, an inscription by the artist Naer het leven: drawn from life.

… [from] a group of approximately 80 figure studies … which Roelant Savery observed at Bohemian markets between 1603 and 1609 … This remarkable group of drawings belongs to the earliest documented example of drawing from life in northern Europe. The figure drawings functioned as a storeroom of ideas. Several of their figures and costumes reappear as vignettes in his finished drawings and paintings.

https://canon.codart.nl/artwork/naer-het-leven/

Simply a small sketch complete with Savery’s scribbled notes about the colours of the peasants’ clothing, but an image of great importance if you’re an art historian trying to analyse how early Netherlandish artists perceived their subjects, and how (and whether) they decided to include closely-observed realism in their pictures. This, of course, is precisely what we’re trying to work out on this course (in my case none too successfully): are we encountering imitatio or ingenium?

This visit to see the Library’s drawings brings out a few minor behavioural issues among our group of twelve students. The drawings are small. To begin to understand what’s going on in them, you need to get your eyes up very close for a very long time. There are twelve of us looking in turn at ten pictures over about two hours. That’s 120 viewings in 120 minutes. But a mere 60 seconds with each of these objects is not nearly enough. One or two of us (one especially) tend to take much more than the notionally-allotted minute. Others hang back diffidently. I detect for the first time a bit of an atmosphere within the group dynamic. It is nothing which might incite hostility or violence or mayhem, merely a slight frisson, a touch of froideur. (Luckily we’re in the French-speaking part of Belgium so I don’t have to find Flemish terms to try to capture the mood.) There might just be a feeling amongst some of us that some others of us are hogging the drawings. It passes, but for a time it was hanging there in the air between us. As for me, I try to spend a little less than my minute with my face right up to each picture, but, while there, to get a good close-up photo with my phone camera which I can enlarge and study later at my leisure.

Day three, morning. Back to KBR, the Royal Library, this time to view the extraordinary permanent exhibition of illuminated manuscripts from the library of the Dukes of Burgundy (https://www.kbr.be/en/treasure/). A big exhibition with many many manuscripts beautifully displayed under glass. Susan tells us about techniques, materials, inks and pigments, about some of the writers and some of the illuminators, about languages and types of script, about iconography and symbols. It’s difficult stuff. For the first and only time, my attention wanders slightly. I drift for a few moments away from the main group and, instead of trying to understand, simply stand looking at unbelievably beautiful, delicate, exquisite works of art and craftsmanship.

Day three, afternoon. Having spent time with paintings, a painted altarpiece, some drawings and many manuscripts, our final session is with sculptures and tapestries. We are at the Art and History Museum (https://www.artandhistory.museum/en), basically a vast and ornate late 19th century cast-iron shed, eerily deserted, with a superlative and seemingly endless collection of – well, it appears to have some of everything, but we only have time for Netherlandish objects from the 15th and 16th centuries. Most mind-boggling of all, a huge set of ten tapestries showing episodes from the History of Jacob, made in Brussels around 1525-1550. I wouldn’t even know where to start in trying to describe them to you. I can only recommend that you visit Brussels at once to goggle at them for yourselves.

And also a room of carved altarpieces. I feel slightly more comfortable here, having worked quite hard over several years at studying these types of objects. Those few of my blog readers who have read my book Random Treasure will know the source of my interest in Netherlandish and Burgundian woodcarvings: I once owned for a short time a small walnut statue of Saint John the Evangelist which was carved around the year 1430 by Claus de Werve. He was the Duke of Burgundy’s court sculptor in Dijon at precisely the same time as Jan van Eyck was the Duke’s court painter in Ghent. Three-dimensional sculptures by Claus look remarkably like two-dimensional paintings by Jan. The two artists almost certainly knew each other’s work, and perhaps knew each other personally.

I’ve looked at many carved altarpieces, in books, online and in museums, and thought I was familiar with the best of them. But there’s a room in the Art and History Museum in Brussels which has three of these retables of astonishing quality, and I don’t recall ever having seen images of any of them before. Of the three, the most spectacular is the Altarpiece of St George, carved in 1493 by Jan Borman II (https://www.kikirpa.be/en/projects/the-altarpiece-of-saint-george). In unpainted oak, Borman depicts seven lurid scenes from the torture and final decapitation of Saint George in the goriest of X-rated detail. If you are ever inclined to think that there’s any truth to the archaic term Flemish Primitives, spend some time with this artwork. Weird, yes. Bizarre, totally. Primitive, absolutely not.

Note to readers: I really recommend you to follow the link to get close-up images of this extraordinary artwork.

Who we were

As I said at the start, there were thirteen of us, the course leader Susan plus twelve students. Our three days together weren’t all hard studying. There were lunches and drinks and evening meals and talk (lots of talk) and conviviality. I’m not usually much good at small talk, especially with strangers, but this was different. With a common purpose and a common area of interest, there was much chat, much sharing of personal information, and a good deal of laughter.

And what a mixed bunch we were. I won’t give their names here, but if any of my fellow students happen to read this blog post, I hope they will recognise themselves and not take offence at anything contained in the following thumbnail characterisations:

A____: the self-appointed guide and social convener of the group, a young, energetic, and delightful citizen of the world. Originally from Arkhangelsk in the north of Russia, now resident with her husband in Geneva, with a place in the mountains and a flat in Central London. Navigated us around Brussels with brisk authority, found the best places for drinks and meals, and was especially solicitous of the needs of the somewhat befuddled couple of oldies from Scotland. Interested in everything to do with art and the luxury lifestyle, and a frequent participant in Courtauld courses.

H____: a retired former lawyer resident in Primrose Hill, London, and a regular attender at art history courses. Always closest to the artworks for the longest, always ready with a comment, an opinion or a lecturette about every item. She should have been annoying but she wasn’t – because her comments and opinions were invariably well-informed and analytical, and more often than not added an extra insight to the fascinating and authoritative narrative supplied by our lecturer Susan. The only time when I felt anywhere near equal to H____’s advanced level of knowledge was when I happened to have heard of Joris Hoefnagel and she hadn’t. How childish!

J____: a retired hospital anaesthetist, originally from the Netherlands but resident in London for 40 years. Spending the early part of his retirement completing a part-time degree in Art History at Birkbeck College, University of London. His wife was also present in Brussels, and he missed a few sessions of the course in order to be with her – but whenever with us, he added to the discussions with a keen eye for what’s going on in a picture, and a good knowledge of how to recognise a saint from his or her saintly attributes (if she’s in front of a castle, she’s Saint Barbara, if he’s shot full of arrows, he’s Saint Sebastian, etc.).

K____: a retired teacher of English as a foreign language, resident for many years in Madrid. A cheerful and well-informed contributor to our Art History discussions.

M____: a willowy, elegant young American woman currently resident with her husband in London. Unsure about her future location and path in life, she recently completed a three-month practical course at the Paris Ritz to train as a pastry chef. Missed parts of the course due to the need for frequent telephone conversations with builders who are currently building a house for her in California. Generally quite quiet during the sessions, but surprised us all in the Royal Library prints and drawings room by carefully questioning the curators about what fire safety precautions were in place to protect the collections.

M____: a delightful young woman from Valencia, Spain, now permanently resident in London, where she works in a senior role in the construction industry overseeing electrical and mechanical installations, mostly in important public buildings. About to start a major project refurbishing the Sainsbury Wing of the National Gallery. An enthusiastic participant in both the study and social aspects of the tour.

S____: not sure where she started out but now living in London, currently working in a senior position for a start-up company managing rewards systems for major employers. A charming, thoughtful young woman who admits to not knowing much about the Flemish Primitives but came on the course to find out about this branch of art – and perhaps to find herself. Unsure about whether her future lies in the secure world of total rewards systems or in something a bit risky to do with art or graphic design – and not yet confident to make that life-changing decision.

W____: a semi-retired widower who owns a suite of rehearsal studios in Burbank, California and who, over a long career in the centre of the music industry, has met and interacted with every famous musician you can think of and many more besides. A collector of luxury wristwatches and an habitual participant in Art History short courses and study tours. Perceptive, well-informed, and sociable, and always on hand when the question being asked was “anyone want to go for a drink and a meal?”

Two ladies who we didn’t get to know. They might have been mother and daughter. Unfortunately the elder of the two was unwell after the first session and didn’t re-appear. The younger woman was sporadically present for parts of the remainder of the course, but was the only participant whom I didn’t get to chat with.

F____ and R____: an aged couple from Edinburgh with modest Art History credentials, having a fantastic time from beginning to end.

Where we were

Apart from the morning trip to Ghent on Day Two, the course was based in Brussels city centre. This was a first visit to Brussels for Frances and me, and we arrived without high expectations of the city itself. The received view of Brussels seems to be that it is a bland and unexciting destination, not much more than a workplace for suited politicians, bureaucrats and business people. Nothing to see here, not much to do. Very little of interest to tourists. Nothing exciting, nothing extreme, no edge. Not like Paris, Amsterdam, Barcelona, Berlin. The most interesting thing in Brussels is a statue of a small boy taking a leak (whom we didn’t visit).

But that’s all wrong! We loved it! A compact city centre; a diverse, laid-back population; fine public buildings; interesting architecture; spacious parks and open spaces; good transport via trams, buses and a simple metro system; and lots and lots of top-quality art from all periods. Combine all this with fine weather, affable company and a multiplicity of good (not great, not cheap) places to eat and drink, and you have a thoroughly excellent venue for a holiday or a break. But of course we weren’t on what you’d call a holiday or a break, because our Art History course demanded a lot of serious brainwork.

So, Brussels: a thoroughly excellent venue for a group of interested and enthusiastic people wanting to know more about the Flemish Primitives. I can’t recommend it highly enough.

What we paid

A Courtauld three-day study tour isn’t cheap. You wouldn’t expect it to be. You get exceptional attention and tuition from one of the leading art historians in the world, and you get privileged access and closeness to some of the most beautiful objects in the world.

It isn’t all that expensive, either – no more than, say, a long weekend ski-ing in the Alps, or a three-day ticket plus on-site catering at Glastonbury. If you like art and art history, frankly it seems quite a bargain.

You make your own travel arrangements and book your own accommodation. Some of our more prosperous fellow students stayed at the Hyatt and similar hotels, but Frances and I booked a small self-catering apartment which was utterly charming in its style, furnishing and décor. At the same time however, it was totally unsuited to our elderly needs. 54 steep steps up to our attic floor through a family house and past a huge growly dog and a miaowing cat. Then a further 14 highly-polished slippery wooden steps (with no handrail) up to our mezzanine sleeping platform. A microwave cooker but no hob or oven for cooking. No washing machine or television. No warning about any of the above in the property details. Never again! Next time, for us oldies, a hotel.

What you should do

Giving a glowing five-star review to an event of any kind can be problematic. The danger is that the review’s publication might increase public interest and demand for places to such an extent that if I want to go again, there might not be any space left for me. Fortunately, however, the readership of the Random Treasure blog is so tiny that I have no cause for concern. No danger that anything I say in praise of Courtauld Institute study tours might engender a sudden spike in demand.

Thus I can confidently recommend, without worrying unduly about my own interests, that you should immediately book a place on the next Courtauld study tour, whatever the subject and wherever the venue. In practice, if you try to do so, you will almost certainly be knocked back because the courses are already wildly oversubscribed. The best you can hope for is that Jackie, the all-powerful and super-efficient short courses administrator, will put you on the waiting list in case of cancellations.

Then, if you’re lucky enough to secure a place, I hope that your experience of your course will be as utterly excellent as was mine. Those few readers who have perused previous posts in this blog will be well aware that this blogger is parsimonious with the use of superlatives, but in this instance my praise has been lavish. And I meant it.

Seriously, if you like Art History, and are attracted by any of the course themes or venues, and can afford the cost, then go for it. I’m not saying that it will change your life, but you will learn from the best and, oh my goodness, what a fabulous time you’ll have!

What a fascinating edition of Random Treasure

Makes one feel one has been there

Thanks so much

Anne Black

LikeLike

Thank you Anne 🙂.

LikeLike