In the majority of previous posts in the Random Treasure blog, I have tended to focus upon scarce and unusual objects, sometimes precious, sometimes arcane, occasionally (it must be admitted) a bit weird. Special pieces, standout pieces. But not so today’s choice.

My guess is that most readers will instantly recognise the object in the photograph above as a Willow Pattern plate. More than a few of you will state with confidence that it was made during the nineteenth century in England, most likely in the Stoke-on-Trent area of Staffordshire.

You don’t need to be a ceramics expert to know this much. Many of us will have had plates just like this one in our homes from childhood. Or we’ll have seen them in a grandparent’s house, or at an elderly neighbour’s, or in a seaside bed-and-breakfast establishment. Or perhaps in a new faux-traditional café whose fashionable interior designer has specified non-matched vintage tableware to enhance the old-style British menu of scones, cream cakes, and (for a light lunch) smashed avocado drizzled with balsamic dressing on artisan sourdough.

We’ll have noticed these plates from the corner of an eye as we pass: in daily use on the table, or hung on the wall, or displayed on a shelf or dresser, or lurking at the back of a sideboard, or (if a bowl instead of a plate) on the utility room floor containing food and water for the dog or the cat.

The Willow Pattern was printed mainly on cheap, utilitarian, industrially-produced white earthenware, enabling poor people to dine like the wealthy. Anyone from any class and any income level could for a very low price purchase for their homes and their tables a bright, cheerful, hard-wearing and robust set of crockery. And classy, too, because its appearance was remarkably similar to the delicate and fragile blue-and-white tablewares imported from China: the china which adorned the homes and tables of the rich.

Millions of Willow Pattern plates exist, mass-produced in huge quantities unceasingly for more than two centuries. The Willow Pattern has been by far the most popular design for cheap tableware ever since the late 18th century when transfer-printing was perfected as a decorative process for mass-produced pottery manufacture. So these plates are as common as muck and as cheap as chips, and unsurprisingly there isn’t much respect for them today either among the generality of ceramics enthusiasts or among the wider population.

Millions of Willow Pattern plates exist, mass-produced in huge quantities unceasingly for more than two centuries. The Willow Pattern has been by far the most popular design for cheap tableware ever since the late 18th century when transfer-printing was perfected as a decorative process for mass-produced pottery manufacture. So these plates are as common as muck and as cheap as chips, and unsurprisingly there isn’t much respect for them today either among the generality of ceramics enthusiasts or among the wider population.

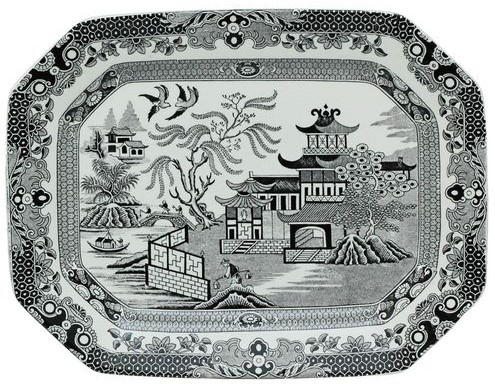

All Willow Pattern ceramics have consistent elements, with only minor variations between manufacturers. There’s a garden, a willow tree, temples and other buildings, a boat on a lake, an ornate fence, a bridge being crossed by three figures. These are the archetypal components of the Willow Pattern story, a pseudo-Chinese fable made up by early marketing people to help popularise the pattern. You can read a version of the story here. And a poem here.

Most Willow Pattern plates were transfer-printed in cobalt blue upon sturdy bright white earthenware and covered with a glossy transparent glaze. But they didn’t only come in blue. Other shades are available. Occasionally you see them transfer-printed in pink, green, brown or black. And sometimes they are in porcelain or bone china.

They weren’t exclusively made in the dozens of potteries in and around Stoke-on -Trent. Similar products came from factories in many other parts of England or Wales or Scotland, and from a few potteries in Belgium, the Netherlands and France which jumped onto the high-volume transfer-printing bandwagon.

And not all blue-and-white transfer-printed plates are decorated in the Willow Pattern. They were made in thousands (yes, thousands) of different designs. If you are so inclined, you can congenially spend a lifetime studying and identifying transfer designs, researching the factories where they were made, analysing minute differences in the engraved copper-plates from which the transfers were prepared, seeking out the source illustrations from which the patterns were derived.

To this end, you can join one or more of the learned societies which exist to promote this interest, for example the Transferware Collectors’ Club (https://www.transferwarecollectorsclub.org/), which has a database of 17,961 patterns. Or the Friends of Blue (https://www.fob.org.uk/), which “offers an opportunity for beginners and experts alike to share their interest in printed pottery”. However, if your passion is for the Willow Pattern only, and you wish to immerse yourself wholly in everything Willow, then the society for you is the excellent International Willow Collectors (https://www.willowcollectors.org/).

And so back to the plate with which I started this piece. It is 9.1 inches (231 mm) in diameter, heavily and rather lumpishly potted, printed in cobalt blue with an entirely standard Willow Pattern transfer. As an example of its class of object, there is absolutely nothing special or remarkable about it. Your first guess was entirely correct: it was indeed manufactured in Staffordshire in the nineteenth century.

In fact, I can be very exact about the plate’s origins. It has helpful information printed in blue on the back, including the initials J. M. & S., and also some impressed numbers 5/76. The initials identify the factory, and the numbers represent the date of manufacture. So, thanks to Geoffrey Godden’s indispensable Encyclopedia of British Pottery and Porcelain Marks, I know:

- by whom it was made: by the distinctly middle-of-the-range firm of John Meir & Son;

- where it was made: at Greengates Pottery, Tunstall;

- when it was made: in May 1876.

I found this plate recently in my regular rounds of the local charity shops. In any given week I’ll see many objects just like this one, but I almost never buy them. Why would I? They are not rare or unusual, and certainly not valuable. So what was it about this particular example that made me pick it out of a sizeable pile of similar objects and pay £5.00 for it? Why on earth did I bring it home to add to all the other clutter in my house?

Ah, now we’re coming to the point. It’s as common as muck. It’s as cheap as chips. But it’s also something rather special: this is a plate with a story to tell. It shouldn’t be here in Britain. Because it was made for export to Brazil.

Yes, Brazil. Who knew? Who could possibly have imagined that British Willow Pattern tableware would be on sale in the shops of Rio de Janeiro in 1876? To be fair, most experts on Staffordshire whitewares and the export thereof will have been perfectly well aware that this was the case. But the rest of us? I think probably not.

And yet, it’s a fact. Staffordshire pottery was exported in huge volumes to all parts of the world, mostly from the port of Liverpool. In the later 19th century, South America was its second most important destination after the USA [1]. In the first six months of 1866, the value of Staffordshire earthenware, china and porcelain exported to Brazil was £87,759 [2]

Thus, my Willow Pattern plate was one among thousands, perhaps millions, of pieces of Staffordshire whiteware made to be sent to Brazil. This destination is revealed by the very helpful underglaze blue transfer-printed stamp on the underside, which features a miniature version of the standard Victorian diamond registration mark above a belt or garland with the inscription WARRANTED THE ORIGINAL STAFFORDSHIRE, within which we find the following message:

Thus, my Willow Pattern plate was one among thousands, perhaps millions, of pieces of Staffordshire whiteware made to be sent to Brazil. This destination is revealed by the very helpful underglaze blue transfer-printed stamp on the underside, which features a miniature version of the standard Victorian diamond registration mark above a belt or garland with the inscription WARRANTED THE ORIGINAL STAFFORDSHIRE, within which we find the following message:

J. M. & S.

ESTEVAO BUSK

& CIA

RIO JANEIRO

We know (because we looked it up in the book) that J. M. & S. stands for John Meir and Sons. But who’s ESTEVAO BUSK? What’s his name doing on the back of a Willow Pattern plate?

I could possibly discover a full answer to these questions if I went to Brazil and spent a long time ferreting around in libraries and archives. This is not going to happen. I’m left with a few scraps gleaned from the internet, plus a big dollop of more or less informed guesswork.

Estevao Busk was an Englishman engaged in the import of British products to Brazil. In England, he was known as Stephen Busk; in Brazil, he translated his forename into Portuguese: Estevao. I can’t speak for certain about his origins, but a session of genealogical searching on www.Ancestry.co.uk has come up with just one likely candidate: Stephen Busk (1821-1900) born in Hunslet, Leeds, the son of Robert Busk, a prosperous flax mill owner who for some years operated an import-export business trading between England and St Petersburg [3].

If I’ve got the right Stephen Busk, he was also the nephew of Hans Busk the Elder (1772-1862), a noted poet, whose works published in 1819 include The Tea, The Dessert and The Banquet. Hans wrote mildly comic poems about polite English meals, and half a century later his putative nephew Stephen sailed polite English tableware across the Atlantic Ocean. I wonder if there’s a causal connection? Don’t suppose so.

It seems somehow more probable that Stephen’s decision to follow a career in the import-export trade was influenced by his businessman dad than by his poetical uncle. Sadly I can’t express an informed opinion either way, having found out nothing at all about Stephen’s private life or business activities in Britain. But from scant evidence gleaned from online Brazilian archives, it is clear that Estevao Busk floruit in Rio in the 1870s, and appears to have floruit in quite a big way – big enough to get a government contract to expand Rio’s docks.

Under a Brazilian government decree of 23rd March 1870:

“The Imperial Government grants to the company that is organized by the businessmen Stephen Busk & Companhia and by the engineer André Rebouças, authorization to build, in the Saude and Gambôa coves, in the port of Rio de Janeiro, import and export docks, and an establishment for the repair of ships [4].”

Saude and Gamboa are coastal inner suburbs to the north of Rio city centre and are still part of the city’s docklands.

There is evidence to show that Busk sailed a fleet of mail steamers from the port of Liverpool to his newly-built docks in Rio de Janeiro, and to the River Plate on the border between Argentina and Uruguay. I’m not able to say whether he personally was the owner of these ships, but he surely owned some or all of the cargoes in the holds of the ships, including, in 1876, a consignment of Willow Pattern plates commissioned from John Meir’s factory in Tunstall and destined for sale in Rio.

Incidentally, in selecting his pottery wares to be carried to Brazil for distribution and retail sale, Busk didn’t confine his choice of design to the willow pattern. If you google Estevao Busk, you can see examples of several other patterns of Staffordshire tablewares bearing the same or a similar backstamp to my plate.

Which makes one wonder about the nature of the 1876 Brazilian market for Staffordshire pottery. Who bought this stuff? And why?

I haven’t found any research which answers these questions but I can suggest a couple of possibilities. It all begins in 1808, when Napoleon’s armies invade Portugal, and the Portuguese royal family flees into exile in Rio de Janeiro, the principal city of their colony of Brazil. Then in 1821, Napoleon safely off the scene, the King of Portugal returns home, leaving his son Pedro behind to rule Brazil on his behalf.

On 7 September 1822, Pedro declares that Brazil is an independent state. He leads a successful war of independence against his father, and is acclaimed as Pedro I, the first Emperor of Brazil. A few years later, he abdicates in favour of his son Pedro II, who reigns for the next 58 years until 1889 when he and his Empire are overthrown in a small revolution and Brazil becomes a republic.

I’m only telling you all this because I knew absolutely nothing about the history of Brazil until I got interested in my Willow Pattern plate, and I thought perhaps that one or two Random Treasure blog readers might be as uninformed as me. Indeed I wasn’t even aware of the existence of an Empire of Brazil until I started my research for this blog post.

The relevant point, however, is that the last four decades of Pedro II’s reign were an exceptional period of peace, prosperity and economic development for Brazil, under the benevolent and enlightened rule of its liberal constitutional monarch Pedro II. Brazil became civilised (in the Western European sense) and rich, and attracted vast numbers of economic migrants from Europe, eager to prosper in the New World.

This brief background sketch allows me to offer you two possible explanations for the huge influx of Staffordshire pottery into Brazil in the 1870s.

- Either: the new immigrant Brazilian middle classes from all parts of Europe and beyond wanted to dress their tables with the most fashionable and best-value crockery arriving in Rio’s docks.

- Or: demand was created more specifically by British immigrants looking for the kind of tableware which served as a reminder of traditional hearth and home.

Since the above explanations aren’t mutually exclusive, you can of course accept both. Or, alternatively, if you don’t think this blogger has worked hard enough to justify either or both explanations, you can find other and probably better-informed answers for yourselves.

One other possibility is that Staffordshire imports might have been bought in their thousands because they were the only affordable tablewares available in the market. This seems unlikely. It is reasonable to assume that alongside Staffordshire whitewares, Rio’s shops and department stores would have sold other competing types of crockery imported from other countries. Sadly, I can’t provide evidence one way or the other, and neither can I cite statistics showing the percentage of market share held by British pottery in Brazil at this time. Some detailed historical research is indicated – which I have no intention to undertake. But we can be confident that Estevao Busk’s imported Willow Pattern plates were just one among many hundreds or thousands of imported commodities offered for sale to Rio’s newly-prosperous middle-class homemakers.

Next question: if my willow pattern plate is supposed to be in Brazil, then why would it turn up in a charity shop in darkest Leith? Again two possible explanations.

- Either: it was re-imported to Britain from South America by someone returning from there.

- Or: it never went to Brazil in the first place.

People who know about these things (that is, some experts active in Facebook special interest groups which focus on British ceramics) think that the second of the above explanations is the likelier. Not all of the pieces made for overseas export ever left our shores. You know the kind of thing: production overruns; substandard and reject examples; cancelled orders. All of which residue would have been sold off locally and cheaply in low-grade discount stores and on market stalls – the 1876 equivalent of today’s pound shops.

Hold on a second. Cancelled orders? Might I have been making up a big fat story about nothing? Could it be possible that Estevao Busk’s consignment of Willow Pattern plates never even made it to Brazil? Could the interesting backstamp be a mere chimera? Was this particular batch of crockery in fact ignominiously sold off in the lowest stratum of the British tableware market, only for a single example to emerge a century and a half later into the hands of a blogger with an overactive imagination?

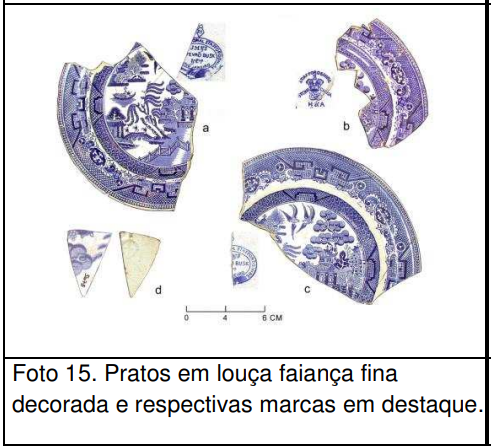

Nope. I have solid evidence that at least two examples from this very batch of plates did indeed reach Brazil. They were dug up in 2010 in the city of Curitiba, the eighth most populous city in Brazil, with a population of almost 2 million, located about 1,000 km from Rio. An archaeological excavation was conducted prior to the installation of underground optical fibre cabling, and in amongst the pottery sherds unearthed were fragments of two plates apparently identical to mine. You can see them as items (a) and (c) in photograph 15 on page 31 of the excavation report [5]. Thus, even if my actual plate never made it to Brazil, some of its companions certainly did.

Nope. I have solid evidence that at least two examples from this very batch of plates did indeed reach Brazil. They were dug up in 2010 in the city of Curitiba, the eighth most populous city in Brazil, with a population of almost 2 million, located about 1,000 km from Rio. An archaeological excavation was conducted prior to the installation of underground optical fibre cabling, and in amongst the pottery sherds unearthed were fragments of two plates apparently identical to mine. You can see them as items (a) and (c) in photograph 15 on page 31 of the excavation report [5]. Thus, even if my actual plate never made it to Brazil, some of its companions certainly did.

And so, I believe I’ve told you everything that I have discovered (or made up) about my Willow Pattern plate: a design inspired by Chinese porcelain, copied in Staffordshire, popularised throughout the United Kingdom and the world, exported to South America by an entrepreneurial Englishman, and rediscovered in a Scottish charity shop. It’s a convoluted tale involving cultural appropriation, colonialism, the rise and fall of an empire, economic development, technological innovation, industrial mass-production, large-scale economic migration, the emergence of the middle classes, changing trends in fashion, early-stage globalisation, and the pervasive influence of international trade.

As if this heady mix wasn’t enough for one blog post, I have made another exciting discovery! My Willow Pattern plate has a special (albeit tangential) connection to an enormously important and historic event: the abolition of slavery in Brazil. Oh yes, it’s not just any old plate.

Although Pedro II was an enlightened and benevolent Emperor, Brazil didn’t get around to getting rid of slavery until 1888, the very last westernised country to do so. One of the prime movers in the campaign for abolition was André Rebouças [6], a prominent activist and abolitionist and a close friend of the Emperor. Rebouças (1838-1898) was a noted military engineer and inventor, who developed a forerunner of the self-propelled underwater torpedo. The son of a white lawyer and a freed black slave, he is celebrated as a key figure in black Brazilian history.

Fittingly for an engineer, Rebouças is today memorialised by a 2.8 km road tunnel running underneath Rio de Janeiro, opened in 1965, which was named after him. A large Brazilian-registered crude oil tanker built in 2015 (gross tonnage: 81,429) also bears his name.

If you’ve been paying close attention (and I don’t blame you if you haven’t been), you have read the name of Andre Rebouças much earlier in this piece. In the 1870 Brazilian government decree quoted above, Rebouças is named as the engineer associated with Stephen Busk in the contract for building extensions to the Rio docks at Saude and Gamboa. So Busk and Rebouças were close business associates.

I can find out almost nothing about Busk, but there is a great deal written about Rebouças. A black man who campaigned successfully for the abolition of slavery. A prominent military and civil engineer. An important inventor. A close pal of the Emperor. A major historical figure.

Can we, then, draw any inferences about Estevao Busk from the knowledge that he had a business relationship with such an important and unusual figure as Andre Rebouças? Does this tell us anything about Busk’s life, personality or attitudes? I’m not sure that it does. Regrettably, Busk must for the time being remain rather a mystery, something of an enigma, remembered not by a portrait, not by a tunnel, not by a tanker, but by a modest Willow Pattern plate.

References

[1] Ana Cristina Rodríguez Y., Alasdair Brooks, Speaking in Spanish, Eating in English; Ideology and Meaning in Nineteenth-Century British Transfer Prints in Barcelona, Anzoátegui State, Venezuela, Historical Archaeology, Vol. 46, No. 3, CURRENT RESEARCH IN SOUTH AMERICAN HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY (2012), pp. 47-62. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23345196

[2] https://www.transferwarecollectorsclub.org/sites/default/files/resources/books/thestaffordshirepotteriesdirectoryfor1868.pdf

[3] https://cferrero.net/tng/getperson.php?personID=I1225&tree=Johnson

[4] https://www.diariodasleis.com.br/legislacao/federal/192179-concede-u-companhia-que-stephen-busk-comp-e-o-engenheiro-andru-rebouuas-organizarem-autorizauuo-para-construirem-ducas-nas-enseadas-da-saude-e-gambua-do-porto-do-rio-de-janeiro.html

[5] https://www.academia.edu/23049614/RELAT%C3%93RIO_FINAL_DO_PROJETO_DE_VERIFICA%C3%87%C3%83O_E_RESGATE_DO_PATRIM%C3%94NIO_ARQUEOL%C3%93GICO_QUE_VENHA_A_SER_IMPACTADO_PELAS_OBRAS_DE_CANALIZA%C3%87%C3%83O_PARA_IMPLANTA%C3%87%C3%83O_DE_CABOS_%C3%93PTICOS_ENERGIA_EL%C3%89TRICA_E_REDE_DE_ESGOTO_NA_%C3%81REA_CENTRAL_DE_CURITIBA_PARAN%C3%81

Just a moment – the dog bowl, if one looks carefully, is not Blue Willow at all, but a modern spoof called Calamityware. Note the pterodactyl, the pirate ship and the serpent? See https://calamityware.com/products/beast-bowls?variant=39264073449495

LikeLike

I guess I was hoping that readers would look at the dog and not so much at the bowl – should have known better! Although in real life I have seen many a dog and many a cat eating and drinking from willow pattern bowls, I couldn’t find an image online other than this one which, as you say, shows a modern comic parody on the traditional pattern. Have to say that I quite like the dinosaurs and robots and other invading objects and creatures, But purists might not be amused, Apologies also to Calamityware for lazily neglecting to cite the source of the image.

LikeLike