This is a luckenbooth. It’s a brooch.

As well as being a brooch, a luckenbooth is a Scottish love token, a group of buildings, a dance, a novel, and a popular design motif in the art of the Iroquois people of the north-east of North America. As you can tell, there are a lot of intermingled stories here which will require some unpicking. But before I get started, perhaps I should explain how I became temporarily immersed in the fascinating topic of the luckenbooth.

The background will be familiar to regular readers of this blog. Yes, you guessed it, I bought the brooch in an auction last week. It was in an online sale in a local saleroom in Portobello, on the eastern edge of Edinburgh. The auction being held under covid lockdown restrictions, I didn’t get to view before bidding. But I liked the look of it from the photo in the catalogue, and thought that if I could win it at a decent price it would make a good present for my wife Frances, who is partial to silver brooches.

In the event, I was the only bidder and got it at a very reasonable price indeed. So reasonable, that if I tell you the hammer price you’ll think me a cheapskate. Worse, Frances, who proofreads these blog posts before publication, will also think me a cheapskate. So please don’t ask about the price.

The Luckenbooth Brooch

Luckenbooth brooches are not rare in Scotland, and many are of much better quality than this thin, lightweight, rather battered, crudely-fashioned object. I can well see why no-one else was interested in buying it. But for me, its very bottom-of-the-range-ness is a key component of its charm.

You can find lots of stuff written online about luckenbooth brooches, and I don’t intend to rehearse it all here. Suffice to say that they are shaped as a heart or as two hearts intertwined, usually surmounted by a crown. They are mostly made in silver, or sometimes in gold or a base metal such as pewter. They often have engraved decoration, some have inscriptions and some are set with semi-precious stones.

Luckenbooth brooches have been popular in Scotland since the seventeenth century or before, and it’s generally true that the simply-made examples are earlier, while ornate versions are more recent. The earliest ones were fastened with a kind of buckle pin. From early in the 19th century this was replaced by a hinged pin, and in the 20th century by a hinged pin with a rotating safety clasp. From around the mid-19th century it would be normal for brooches to be made in sterling silver and assayed and stamped with a hall mark.

A luckenbooth brooch is on display in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, and you can see its picture here. The description on the Museum’s website includes the following:

“Heart brooches are one of the commonest surviving types of Scottish traditional brooch. They are sometimes called luckenbooth brooches, after the stalls round St. Giles Cathedral in Edinburgh, where they were sold in the 19th century. They are also known as witches’ brooches. Small heart brooches were often fastened in children’s clothing for ‘averting the evil eye and keeping away witches’. Mothers also wore them to prevent the witches from stealing their milk. They were frequently given as love tokens. Women wore them at the neck of their shift to close the front opening.”

There are various accounts of the origins of the luckenbooth shape. It might be Celtic in origin. Or Norwegian. Or it might be related to the Irish traditional claddagh ring, which features two hands holding a crowned heart. It might be something to do with Mary Queen of Scots. I have nothing useful or knowledgeable to add to the origin stories you can read on Google.

I do however stand on somewhat firmer ground when it comes to giving an account of the background to the luckenbooth name. It’s an Edinburgh thing.

The Luckenbooths and the Heart of Midlothian

The central section of Edinburgh’s High Street is today laid out very much as it was in the 16th century. Some buildings have been reconstructed, but the street layout is substantially unchanged. This stretch of the famous Royal Mile is midway between Edinburgh Castle at the top of the hill and the Queen’s Palace of Holyroodhouse at its foot. On the south side is the mediaeval St Giles Cathedral, behind which are Parliament Square and the old Scottish Parliament buildings; on the north side are tall tenements flanking the neoclassical City Chambers, built as the Royal Exchange in 1760 upon the many-storeyed foundations of very much earlier structures.

Now, in 2021, this stretch of the street is spacious and elegant. But it didn’t used to be. If you had been standing downhill (east) from St Giles a few centuries ago – approximately where the statue of Adam Smith now stands – and looking uphill (west), you wouldn’t have been able to see today’s open vista of fine old buildings leading up towards the Lawnmarket and Castle Hill. Instead you would have seen the gable end of a narrow row of venerable tenements which blocked the view and almost completely obscured the entire length of the north side of the Cathedral. To the right of this row, the main thoroughfare was cramped and crowded with traffic. To the left, a dark, malodorous alleyway just a few feet wide separated the cathedral wall from the arcaded frontages of the tenements. This sordid, squalid lane was known as the Stinking Style.

At the western, upper end of the row stood the Old Tolbooth, a strongly fortified but decrepit and mouldering pile originating in the 14th century, which was used as a prison. The building was known as the Heart of Midlothian, and the position of its entrance is marked today with a heart-shaped mosaic of setts (cobbles) set into the roadway. Apparently it’s an old Edinburgh tradition to spit upon this mosaic, but I’ve never seen it done, and it seems somehow unlikely to be perpetuated in these covid-conscious times.

If you want to know what it was like to be incarcerated in the Old Tolbooth Prison, you can do no better than to read Sir Walter Scott’s wonderful novel The Heart of Midlothian, published in 1818.

The reason why I switched into travelogue mode to write the last few paragraphs will now become apparent. Here it is: the lower storeys of the narrow row of tenement houses were subdivided into countless small shops or cubicles occupied by craftsmen of all trades and open to the Stinking Style. On the opposite side of the Style, hard up against the north walls of St Giles, impoverished purveyors of low-grade fancy goods set up tiny timber sheds known as krames (sometimes spelled creams) from which they plied their wares. At close of business every evening for hundreds of years, all the tradespeople on both sides of the lane would shut up their crowded premises with lockable wooden shutters. They were locking their booths. Or, in Scots parlance, luckenbooths. Get it?

While writing this piece it has occurred to me to wonder if there is any historical or folkloric connection between the heart-shape of brooches bought in the luckenbooths and the heart-shape associated with the adjacent Tolbooth prison building. I haven’t found any support for this notion in my not-especially-rigorous research, but it does seem an interesting coincidence.

The Luckenbooths and the Goldsmiths

A few yards to the south of the Old Tolbooth, in the area now known as West Parliament Square, a grand building was constructed in the 18th century for the Incorporation of Goldsmiths, the craft guild which regulated the making of goods in precious metals through strict membership rules and the imposition of the assay system and hallmarking. In order to be close to Goldsmiths Hall, silversmiths and jewellers tended to set up their shops and stalls very close by:

“In Edinburgh in the late eighteenth century Parliament Square was the centre of goldsmith activities which included silversmithing and jewellery manufacture; they were the most numerous of the tradesmen who occupied the Square. Deitert [in Dietert, R R and Dietert, J M, Scotland’s Families and the Edinburgh Goldsmiths, p276] records twenty seven goldsmiths who had their shops in Parliament Square or the Luckenbooths and a dozen more in the adjacent High Street.” [1]

With so many jewellers and silversmiths in the immediate area, it’s no surprise that the most characteristic item of traditional lowland Scottish jewellery, a brooch in the shape of one or two hearts surmounted by a crown, should come to be known as a luckenbooth brooch. If you wanted to buy one as a love token for your sweetheart or a charm against witches, you visited the luckenbooths.

As well as buying jewellery in a luckenbooth, you can also dance the luckenbooth.

Dancing the Luckenbooth

I have been resident in my adopted country of Scotland for more than half a century and have come to love most things about it. Sometimes I even have starry-eyed notions of how Scotland might be able to succeed and prosper as an independent nation if separated from the baleful influence of Westminster and Whitehall.

But there are some things Scottish which, however hard I exert myself, I can’t bring myself to love. These include Golf, Haggis, Whisky, Irn Bru, Munro-bagging and Scottish Country Dancing.

Scottish Country Dancing is a pastime which many Scots learn in childhood and is a popular feature of most Scottish gatherings, balls and celebrations. It should always be a pleasure to watch – or to join in with – a set of well-trained and well-turned-out dancers enjoying themselves in a Dashing White Sergeant or Eightsome Reel or Strip the Willow to the fiddle and accordion music of a ceilidh band.

Unfortunately I have rarely felt such pleasure. In my experience Scottish Country Dancing invariably comes in two varieties. There’s the kind seen late in the evening at Scottish weddings, where large, kilted, alcohol-fuelled prop-forward friends of the groom put the same energies into their gyrations as they do into their rugby practice, often leading to the same sorts of serious injuries. And there’s the professional kind seen at afternoon ceilidhs and competitions, where local Demonstration Teams will show off their precision in the execution of extraordinarily complex dance manoeuvres. Among which is a dance called The Luckenbooth Brooch.

Unfortunately I have rarely felt such pleasure. In my experience Scottish Country Dancing invariably comes in two varieties. There’s the kind seen late in the evening at Scottish weddings, where large, kilted, alcohol-fuelled prop-forward friends of the groom put the same energies into their gyrations as they do into their rugby practice, often leading to the same sorts of serious injuries. And there’s the professional kind seen at afternoon ceilidhs and competitions, where local Demonstration Teams will show off their precision in the execution of extraordinarily complex dance manoeuvres. Among which is a dance called The Luckenbooth Brooch.

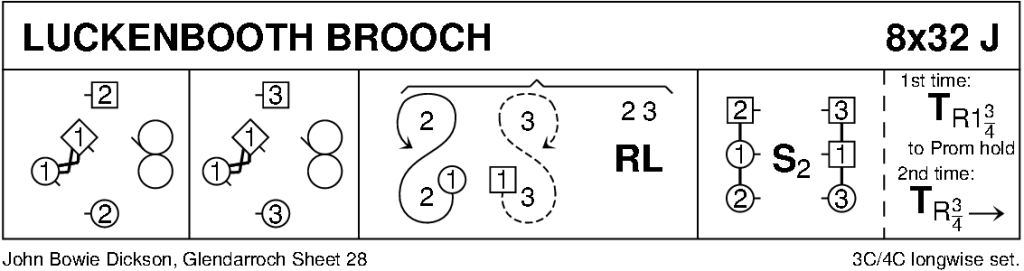

This dance is so called because the dancers move in an intertwined heart shape which is said closely to follow the traditional shape of the luckenbooth brooch, as you can easily see from the following diagram borrowed from the Scottish Country Dancing Dictionary [2]:

Here’s a short video showing the dance. Note the intense facial expressions adopted by the dancers, indicative of the fact that Scottish Country Dancing, when done in strict accordance with the rules as set out by the Royal Scottish Country Dance Society, is a very serious business.

And now for a change of continents.

The Luckenbooth and the Iroquois

In my last blog post (which you can read here) I felt inadequate to the task of writing about Japanese ceramics (not that it stopped me) partly because I have never visited Japan. In this post I’m about to cross the Atlantic Ocean to the North-Eastern part of North America – an area which I have indeed visited. In fact I once lived there for a year, in the land of the Mohawk, one of the constituent Five (later Six) Nations of the Iroquois or Haudenosaunee people.

Sadly my time in 1969-‘70 as a student at Union College, Schenectady, in upstate New York did not include any contact with any Native American people. There weren’t many there. Most surviving members of the Mohawk nation had been driven north into Ontario more than a century earlier, after a few hundred years of trading with and/or persecution by successive waves of foreign incomers: the French, the Dutch, the English, the Yankees, and the Scots.

As a young student much preoccupied with all the activities that late 1960s America had to offer, I regret that I neglected to pay any attention to the history of the first occupants of the land that I was inhabiting. But I was always dimly aware of their former presence – from the place names that they left behind, adapted and transliterated from the Iroquoian language by the European settlers who displaced them. Some examples: the Mohawk River, which ran a few blocks away from the campus; the city name Schenectady itself, meaning beyond the pines; Saratoga, the hillside country of the quiet river; and many more. You can learn a lot about the history of a place from its directional signs.

Somehow, at some time in this largely undocumented past, it isn’t known how or when, a quantity of luckenbooth brooches passed from the hands of (presumably) Scots traders or settlers or invaders, and into the hands Iroquois Native Americans. The likeliest explanation is that it happened from the mid-eighteenth century and the brooches were exchanged as trade or barter goods. The Scots traders acquired furs for themselves and for export to Europe; the Iroquois trappers acquired silver and jewellery for themselves and for the women who ruled the clans in the matriarchal Iroquois society. Whether or not this was a fair exchange is outwith the scope of this blog, but it’s clear that the luckenbooth brooch was a hit.

And so the heart surmounted by a crown became a favourite design motif copied and adapted by Iroquois silversmiths. Here is an example from the McCord Museum in Montreal [3]. The similarity to the Scottish original is unarguable. Unfortunately I have been unable to find for you an early image of a member of the Iroquois people actually wearing a luckenbooth brooch.

The linkages between heart-shaped brooches of the Scots and the Iroquois were first discussed in detail by Arthur C Parker in an article in the journal American Anthropologist in 1910 [4]. In a second paper the following year he says:

“The Iroquois Traveller, faithful to the precedents of his sires in the olden days, generally fastens a double heart brooch to his coat or vest as an emblem of his nationality and as a hailing sign to the wanderers of his tribe. Never does he suspect that the motif of his emblem is anything but a genuine product of his own ancestors … he never dreams of the canny Scot of earlier times.” [5]

I’m not altogether clear on how the behaviour of the Iroquois traveller associates with the stereotypical quality of canniness in the Scots, but there you go.

Iroquois-made luckenbooth brooches are much more collectible and highly sought after today than their Scottish originals. But I find it a strange and appealing thought that if one were deploying a metal detector on the banks of the Water of Leith in Edinburgh or the Mohawk River in Schenectady, there might be a more-or-less equal chance in either location of uncovering a lost luckenbooth brooch.

The Luckenbooth Book

For completeness in this rundown of everything Luckenbooth, it is essential that I give a mention to a brand-new novel entitled Luckenbooth by Jenni Fagan, published in January 2021 by William Heinemann [6]. The action of the book takes place in Number 10 Luckenbooth Close, “an archetypal Edinburgh tenement”, and begins in the year 1910 – so the street address must be a fictional invention, the real Luckenbooth tenements having disappeared much earlier.

For completeness in this rundown of everything Luckenbooth, it is essential that I give a mention to a brand-new novel entitled Luckenbooth by Jenni Fagan, published in January 2021 by William Heinemann [6]. The action of the book takes place in Number 10 Luckenbooth Close, “an archetypal Edinburgh tenement”, and begins in the year 1910 – so the street address must be a fictional invention, the real Luckenbooth tenements having disappeared much earlier.

I haven’t read the book yet, but it has received excellent reviews and I intend to get a copy and read it sooner rather than later.

A Dodgy Luckenbooth Brooch

Let us now return to my starting point in this blog piece: the luckenbooth brooch which I recently bought for Frances. Wouldn’t it be splendid to think that it was originally made by and purchased from a silversmith based in one of the luckenbooth krames? But it wasn’t. The dates don’t fit.

Because of the style of pin used to fasten the brooch, I estimate that it must have been made not earlier than the second half of the 19th century. By then, the luckenbooths were long gone. Goldsmiths Hall was burned to the ground in 1796, and then in 1817 the entire row of tenements along with the Old Tolbooth prison were flattened by order of the Town Council in an Improvement Scheme. Now there’s nothing left to show that they ever existed except for an outline of the north-facing frontage laid out in brass markers in the road.

There’s another reason why the brooch is unlikely to have come from a member of the Incorporation of Goldsmiths: it’s a bit dodgy. That doesn’t mean that I don’t think that it is a genuine period piece of traditional Scottish jewellery: it is. And it doesn’t mean that I don’t find it perfectly charming: I do, and I hope Frances does too. But it’s not really what you would call a good quality piece.

Let me try to explain what seems (to me) to be not quite right about it.

- At 58 mm tall it’s too big: it looks a little showy, a little flashy; there’s nothing subtle or understated about it. It doesn’t exhibit much class, and it doesn’t reveal much taste in either its maker or its purchaser.

- It’s paper-thin: whoever made it clearly wanted to get maximum show for minimum input of metal. The brooches were made by pouring molten silver into a mould, and this example has been cast as thinly as it could possibly be, and feels lightweight and flimsy. It seems a mystery how it has lasted for around a century and a half without being crumpled and broken.

- It’s roughly made, unsophisticated and folksy: the casting is rough, the engraving is cursory, the fastening pin is attached clumsily. If you were buying it new today it is the kind of thing you might expect to get from an amateur artisan at a market stall and not from a silversmith in a jeweller’s shop. Likewise if you were buying it new in, say, 1860.

- It doesn’t have an assay mark, which means it is unlikely to have been made by a silversmith regulated by the Incorporation of Goldsmiths. I haven’t tested it for the purity of the silver, but my suspicion (based on the experience of more than 60 years handling small pieces of silver as a coin collector) is that its silver content is significantly below the Sterling standard of 925 parts per 1,000. It feels slightly harder and tougher than sterling silver, which suggests some kind of alloy, and which might in turn account for its intact survival.

With no maker’s mark and no history it is impossible to say who made this brooch or who first bought it. It is simply a lovely old brooch with an interesting back-story but a total lack of provenance.

If you wanted to know the tale of its origins and history you would have to make up a story … which is what I have done, and you can read the first chapter of it here.

References

[1] https://parliamentsquareedinburgh.net/goldsmiths/

[2] Copied from https://www.scottish-country-dancing-dictionary.com/krdiagram/luckenbooth-brooch.html

[3] http://collections.musee-mccord.qc.ca/scripts/viewobject.php?Lang=1§ion=196&accessnumber=M10543&imageID=269662&pageMulti=1

[4] https://anthrosource.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1525/aa.1910.12.3.02a00010

[5] https://www.jstor.org/stable/659649?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents

[6] https://www.penguin.co.uk/books/1099360/luckenbooth/9780434023318.html

Fascinating, thank you – I’ve inherited a Luckenbooth brooch, so will re-read in more detail with it in front of me (I can assure you it’s not one of the bejewelled variety!). To my eye, the one you bought has something Nordic about it – have you checked their silver content? There was a sunken hoard they found in the 1980s and some contemporary Oslo jewellers made official copies and they had a similar decorative markings …

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Anne. I’m about as sure as I can be that the brooch I bought for Frances is a Scottish luckenbooth, but a little research has revealed that there is indeed a Norwegian solje silver brooch which is part of the traditional national dress. These are sometimes made in the form of a crowned heart but it seems that an essential feature of solje brooches is that they include a group of ovoid or circular dangling drops. By comparison the luckenbooth is quite austere.

LikeLike

Fascinating and informative as ever Roger, every day’s a school day on Random Treasure. I certainly had no idea that the motif had crossed the Atlantic and found lodgement among the Native Americans. Back in 2010 when I was trying to promote a 200th anniversary celebration of ‘The Lady of the Lake’ (perhaps you remember that ill-fated ploy) I sketched a design for a luckenbooth variant topped with a crown and a stag’s head as a possible logo and saleable souvenir emblematic of Scott’s themes in the poem. But I was disconcerted to find that my West of Scotland colleagues had no awareness whatsoever of luckenbooths.

I enjoyed your deft demolition of Scottish Country Dancing, and entirely share your disdain for the extremes of the form. Not quite so keen on your distaste for haggis, whisky and Munro-bagging – you might expect me to rise to that bait. My favourite Italian restaurant in Glasgow does a superb cannelloni haggis (as a takeaway in present constrained circumstances) which you might well place in the same category as wedding-reception-style celidh ‘dancing’ …

I trust Frances is taken with her brooch despite your critical evaluation!

LikeLike

Thank you Bob. As I’m sure you know, I have nothing against climbing Munros per se (although you are not likely to find me doing it); my beef is more about the dedicated Munro-baggers who assert their moral superiority over me as a mere townie leading an impoverished lifestyle, because they have bagged ’em all and I haven’t bagged any. Nothing against haggis and whisky either except that they happen not to be to my taste. Many Scottish delicacies are indeed to my taste (although I might also draw the line at mutton pies and potted haugh).

LikeLike

Thank you for this discourse on this subject and others… I actually came across it while doing a deep dive on a particular brooch in the National Museums of Scotland, not being able to get there any time soon myself. For context, I am a traditional Silversmith at the world’s largest living history museum. I would, with great apologies, add only this bit: That while many folks (even in the 18th century) presume silver and gold are primarily cast into form, they are not. The precious metals are primarily hammered out from the ingot into sheet and pierced with drill and jeweler’s saw, the latter of which dates to about 1700… It was actually cheaper and faster that way. It looks like the piece you acquired is early 19th century by its thinness and style, and had many flaws (happened often) in the ingot from which it the sheet was plattened, and/or was hammered out on a damaged anvil. They were making them as thin and affordable as they could in those decades, as we often see with flatware of the period. The bar pin on back looks to be a later one or a repair, and if it were heated up sufficiently when it was done, that would make the silver even more bendable by annealing it. It’s engraving isn’t overdone like most Victorian era ones, so I think it’s likely earlier than 1840. Many provincial pieces did not make it to a Hall for assay, either. So I wouldn’t sell it too short: it’s a nice piece with more character and history (albeit unknown) than one of the later romanticised tourist pieces. I’ll now set down the coals I’ve been bearing towards Newcastle. Thank you again, and I’ll continue to appreciate travelling vicariously via your articles.

LikeLike

Hello Chris.

Thank you for reading my blog and for taking the time and trouble to comment on my wife’s Luckenbooth brooch. Like you, I had originally thought it was cut from a thin (very thin!) sheet of silver, but I read somewhere that these items were generally cast in moulds. Unfortunately I didn’t make a note of the reference, but some must indeed have been cast because there is an example of a luckenbooth brooch mould in the National Museums of Scotland collection (sadly not illustrated on their website but see https://www.nms.ac.uk/explore-our-collections/collection-search-results/mould-brooch/14180).

I believe the pin is original to the piece but has probably been repaired at some time. With regard to its age, it would be nice to think that it is from quite early in the 19th century, but pieces such as this could have been made by local or travelling artisans anywhere in Scotland over much of the century.

I haven’t tested the purity of the silver, but suspect that if it had been submitted for assay it would have been rejected for failing to meet the Sterling standard.

Re-reading my blog piece, perhaps I do sound a bit harsh. In fact I think the brooch is delightful – but maybe to be appreciated more as a lovely example of folk art than as a masterpiece of silversmithing!

Please do let me know if there’s any way I can assist you with your researches at the NMS: I live fairly nearby and visit the Museum quite often.

Somehow, despite having visited many major US museums, I have sadly missed out on Colonial Williamsburg – an omission which I hope to correct in the future.

Best wishes.

LikeLike