Previously, in the Missing Monk Mystery …

In the first two chapters of this rather long blog post, which you can read here and here:

- I wrote about the oil painting by Daniel Maclise entitled Caxton Showing the First Specimen of His Printing to King Edward IV at the Almonry, Westminster, which was first shown in an exhibition in 1851;

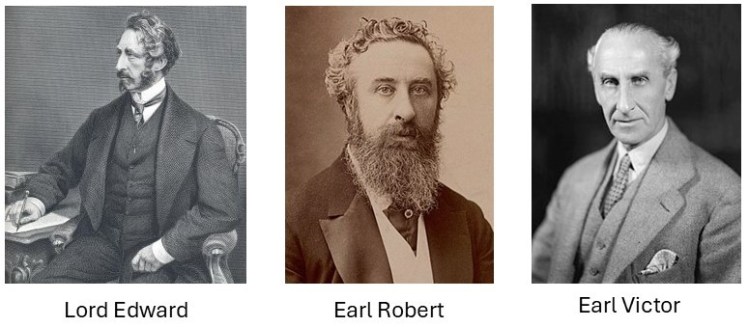

- and how it came into the ownership of Robert, the First Earl of Lytton in 1876, and was hung in the State Drawing Room at Knebworth House, where it still hangs today – but in a mutilated state with a section cut off from each side;

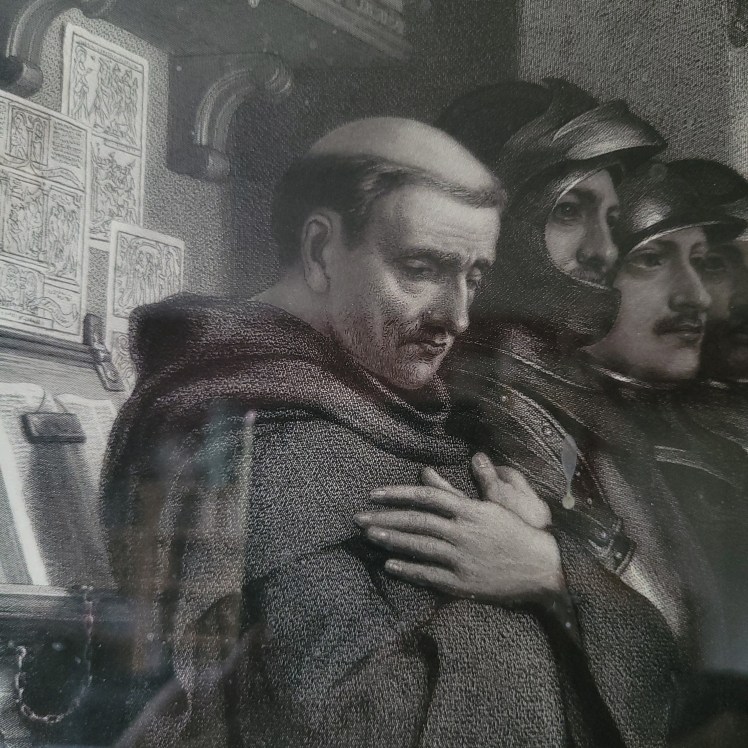

- and that the missing piece on the left-hand side contained as its main feature a depiction of a scowling Monk;

- and I set out to investigate why the Monk was cropped from the picture and who was responsible.

In this final chapter I have five possible explanatory scenarios to offer you. Take your pick.

Scenario #1: Accident

The painting had to be cut down because it was somehow damaged.

It was suggested by the Hamilton Kerr Institute when they restored the painting in 2007 that a possible reason for cropping the painting could be “removing a damaged section from one side of the canvas and mirroring the removal on the opposite side in order to retain compositional balance”.

Damaged? How damaged? Did it fall off the wall? Was it subjected to a sword thrust or a bullet during an altercation in the State Drawing Room? Did Earl Robert or one of his guests inspect the Monk too closely with a candle in hand? Woodworm? Dry rot?

Really? But if it got damaged, why wouldn’t they simply get it mended? It was an important, famous painting. Reducing it because of damage would involve cutting both sides of the canvas, replacing the side stretchers, re-framing. You would have to send it away to a picture restorer and it would be an expensive job.

If you were sending it to a restorer, why wouldn’t you simply get the damage restored instead of having the painting cut down? Then you could be spending your money on keeping the picture as intact as possible, while retaining at least one side stretcher and the original frame.

By the end of the 19th century art restoration was a well-established and highly respectable profession, although many of the restoration techniques used were very much cruder and more extreme and interventionist than would be tolerated today. Art dealers such as Joseph Duveen and connoisseurs such as Bernard Berenson didn’t hesitate to get their Old Masters repaired and touched up and even altered to suit the tastes of the moment.

In the case of Maclise’s Caxton painting, restoration would be straightforward because the picture was only a few decades old and appropriate materials could be easily procured by a restorer. And it was well known what any damaged or missing sections were supposed to look like, because there was an incredibly detailed engraving available for consultation which had been prepared in collaboration with the artist.

So it simply wouldn’t have made sense if the painting were damaged for its Lytton owner to have it savagely cut down, and in the process to excise an especially important section of the composition (the Monk).

Sorry, experts of the Hamilton Kerr Institute, but I don’t accept that scenario at all.

Scenario #2: Convenience

The painting had to be reduced in order to hang in its chosen position on the wall at Knebworth.

The image above shows the Knebworth State Drawing Room, a chamber of immense size done out in the most outrageously gorgeous and overstuffed high-Victorian taste. The Caxton painting is to the right of the fireplace, flanked by smaller pictures, three to the left and two to the right. I can’t tell you what the smaller pictures are, but I suspect they are valuable and important and painted by the best artists. However, it’s perfectly obvious that it wouldn’t be all that much of a problem to display Maclise’s masterpiece in more or less the same space if (as it formerly was) it were about 18 inches wider than it is now.

All you’d need to do is shift the smaller pictures over a bit, or perhaps find a different wall for the three pictures on one side or for the two on the other. No problem. Space issues certainly can’t be a reason to hack nine inches off either side of the Maclise. There is no shortage of wall space at Knebworth, and it’s not as if there would be a danger of spoiling the house’s minimalist aesthetic by overcrowding the pictures.

So: I’m dismissing my second scenario. Three more to go.

Scenario #3: Taste

It’s all the fault of Sir Edwin Lutyens.

We have previously established that the picture was re-framed when it was cut down. If you look at a detail of the late 1800s photo (below left) you can see that the Victorian frame was ornate and gilded. But the recent photo (below right) shows that the current frame is made from a simple varnished hardwood moulding. The image reproduced above showing the fireplace wall of the Drawing Room reveals that the Maclise painting is an anomaly in this respect. All the other pictures are in fancy gilt frames. The Caxton picture is the only one in a simple frame. That seems odd.

It’s a famous picture with important Lytton family associations. It’s in a very prominent position in the Knebworth State Drawing Room. Why would they dispense with the big in-your-face blingy frame when they dispensed with the Monk?

I have a theory.

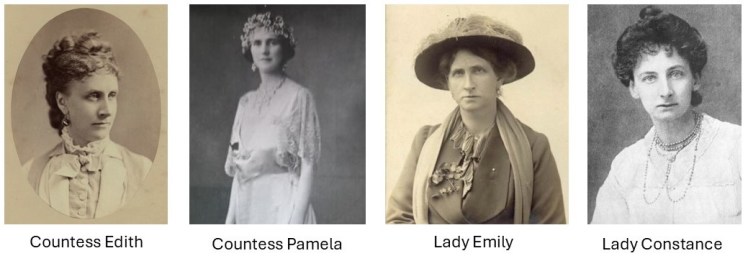

In 1897, Lady Emily Lytton, the sister of Victor, the then current Earl of Lytton (Edward’s grandson, Robert’s son, keep up!), married an up-and-coming architect called Edwin Lutyens. The marriage led to “a host of projects at Knebworth”.

Then, when in 1902 Victor himself got married

“… to the beautiful, lively Pamela Chichele Plowden, Lutyens [helped] his new sister-in-law to bring Knebworth House into the twentieth century, culling some of the heraldic beasts and gargoyles of the Victorians.” [1]

Anyone who has seen any of the buildings and monuments designed over a long career by Sir Edwin Lutyens will know that his style of house design differs in every respect from the ornate Victorian style of Knebworth House. His architecture has clean lines and solid profiles, with influences from Clacissism, from the Arts and Crafts Movement and from early Modernism. Without exception, his houses embody the very antithesis of Gothic Revival romanticism.

Heron en.wikipedia.org, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

We can be confident that if Lutyens framed a picture, it would be in varnished wood and not in encrusted gilt.

So maybe it was Lutyens who, in his culling of heraldic beasts and gargoyles, at the same time culled the gloomy, glowering, obsolete Gothic Monk from Maclise’s painting? And maybe he then reframed the positive, forward-looking central portion of the composition in a plain wooden frame characteristic of his country house style?

I tried this thought out on Jill Campbell, the Knebworth archivist, who replied:

“during the Lutyens redesign and decoration the State Drawing Room was left untouched, so it would be very unlikely he had anything to do with the cropping of the painting”.

Ho hum. Another clever theory bites the dust. Read on.

Scenario #4: Complaints

The scowling Monk had to go because he was the most miserable thing in the whole State Drawing Room.

This scenario is an outlier. I don’t set much store by it. But I guess it’s possible that a picture, or one element in a picture, might spread such alarm and despondency amongst its viewers that the owners of said picture feel compelled to take drastic action.

Drawing rooms exist in order for their proprietors to provide for their guests a peaceful and tranquil after-dinner experience, which must include the contemplation and appreciation of suitable artworks. In the Knebworth State Drawing Room, surely the very apotheosis of the English Great House Drawing Room, this must be even more true than in other drawing rooms, including, for example, dear Random Treasure blog readers, your drawing room and mine.

Let’s suppose that a picture is so disturbing, so depressing, so upsetting, that it casts a gloom over the entire assembled company. The occasion is ruined. Arguments break out amongst the gentlemen. The ladies take to their smelling salts. The guests depart dissatisfied. There might be a duel on the front lawn.

A picture might be a great picture – the Massacre of the Innocents (Poussin), the Scream (Munch), the Raft of the Medusa (Gericault), Guernica (Picasso) – but that doesn’t necessarily mean that you’d want it on the wall in your Drawing Room.

Maybe, just maybe, the Monk was just such a downer at Knebworth, as he lurked sinisterly within the otherwise positive and inoffensive composition of Caxton showing off his apparatus to the King. Maybe he had to go.

In order for this theory to hold any water at all, we need perhaps to set the Monk a little more closely in context than heretofore in this piece. Why is he there? What is he doing in the picture? As we saw earlier, Lord (Edward) Lytton described the Monk’s role as representing:

“the whole transition between the mediaeval Christianity of cell and cloister, and the modern Christianity that rejoices in the daylight”.

Yes indeed, the Monk is emblematic of the bad old ways of the middle ages and before, when vast power and influence were wielded from the monasteries. Here in the Almonry at Westminster in 1477, the Monk stands for everything old-fashioned and outdated that is about to be overturned and replaced by the Reformation and the Renaissance, in large measure through the agency of the printing press.

This is what the Monk foresees:

- In 1517, Martin Luther nailing his 95 theses to the door of All Saints’ Church in Wittenburg and kicking off the Reformation

- In 1536, King Henry VIII turning Protestant and ordering the breaking up and looting of the wealthy, powerful monasteries and their huge estates

- Caxton’s printing press knocking the bottom out of the lucrative monastery-dominated manuscript-making market

- Literacy and education overcoming the mediaeval Catholic church’s exercise of rule by superstition and mystification

- Vernacular scriptures and liturgy replacing the Latin bible and mass, making Christianity understandable and accessible to the common people and the peasantry.

The Monk can predict that within a few years from Caxton’s demonstration of his new printing machine, Monasticism’s gonna be toast. Little wonder that he looks so gloomy.

We can imagine that some – perhaps many – of the dinner guests gathering in the Knebworth State Drawing Room after a big dinner in the Dining Room would be well able to take a look at the Caxton painting and immediately (or maybe with a little prompting) see exactly what’s going on with the Monk: what he’s thinking, how he’s feeling, and what fears he may have for his personal future and the future of monkery.

Some guests – perhaps many – might be disturbed. They might feel a chill passing through the convivial company. Rumours to this effect might reach the ears of the host or hostess, who might as a consequence come to the conclusion that Maclise’s painting would be an altogether more positive and successful composition, and much more compatible with the joint postprandial Drawing Room tasks of conversation and digestion, if the Monk simply weren’t there.

However, I might argue with myself that this scenario is just plain nonsense because there’s a much easier and cheaper way to resolve complaints from any house guest whose visit to Knebworth has been ruined by the appearance of the Monk. Instead of cropping the picture, why not simply have the Monk’s face overpainted to look like someone more appealing? How about turning him into a smiling Monk who benignly foresees the future benefits that printing will bestow upon generations no longer subjugated to the cruel and superstitious power of the old church? Easy-peasy. Visitors will leave satisfied.

It’s a powerful argument, powerful enough perhaps to overturn the whole of my Fourth Scenario.

Scenario #5: Prejudice

The scowling Monk is a portrayal of a real person, and someone at Knebworth wanted him out of the picture.

My fifth and final putative explanation of the Missing Monk Mystery is my favourite. The Monk (or conceivably one of the other minor characters at either edge of the original composition) was removed from the painting because his real-life contemporary model had become persona non grata in the eyes of someone at Knebworth.

Some Victorian narrative paintings came with a handy key to enable you to recognise the portraits included by the artist in the composition. Take for example A Private View at the Royal Academy, 1881 by William Powell Frith, depicting a crowd of “politicians, poets, prelates, philosophers and philanthropists, jurists, actors and, of course, fellow artists” whose “positions in the composition are carefully calculated: as the preliminary sketch reveals”, and whose “frame even provided a crib so that viewers could identify each of the personalities portrayed” [2].

Maclise in his Caxton picture wasn’t showing his models as themselves but was dressing real people in mediaeval garb as characters in his narrative picture. As we have seen in Chapter 2:

- Queen Elizabeth looks remarkably like Queen Victoria;

- Lord Rivers is claimed to be a portrait of Lord (Edward) Lytton;

- William Caxton appears to be a self-portrait of Daniel Maclise.

It seems therefore reasonable to assume that there are other hidden or not-so-hidden contemporary portraits among the historical characters depicted in the painting.

If a real person whose face appears in a painting subsequently falls out of favour with the owner of that painting, then it would be a good reason to have the offending physiognomy excised from the image.

For this theory to stand up in relation to the Monk, we would need

- Firstly, a positive identification of the victim – the person who modelled for the Monk and who was later expunged from the painting

- Secondly, a positive identification of the suspect – the person in a powerful position at Knebworth who felt compelled to exclude the victim from the painting.

I believe I can at least go some way towards identifying both the possible list of victims and the possible list of suspects. Here goes.

Victims

Who modelled for the Monk? We need to look closely to see if we can find any resemblances to a real life original.

We know from Maclise’s fan letter to Lord Lytton (see Chapter 1) that the Caxton painting was in preparation in January 1849, and that it was complete by the summer of 1851 when it was exhibited at the Royal Academy.

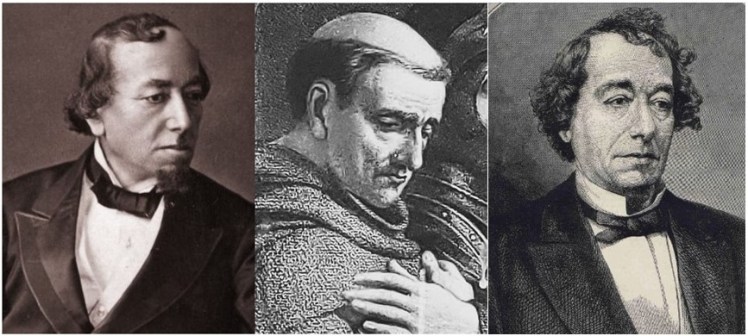

We don’t possess a close-up of the Monk when he was still a part of the original painting, but we can assume that the Monk as he appears in the 1858 Maclise-approved engraving closely resembles the image in the painting. From this we can see that the gentleman who modelled for the Monk is not young and not old: let’s say that in 1851 he is between 30 and 50 years of age.

This indicates that he was born between 1800 and 1820 – which makes him a contemporary of Lord Lytton (born 1803) and of Daniel Maclise (born 1806), and also of other members of their close circle, including John Forster, the painting’s original owner, and Charles Dickens (both born 1812).

The Monk’s appearance is distinctive: he has a heavy, slightly bulbous jaw, thick eyebrows, long earlobes, a large nose and what might be described in romantic fiction as a sensitive (or possibly sensuous) mouth. We can’t say anything about his hair except to assume that the model’s barnet would have to be changed significantly by the artist to produce the Monk’s tonsure.

From this strong Identikit image it should be possible to identify the model, who (if this Scenario is to have any credibility) was a gentleman in favour with Edward Lytton in 1851, and presumably still in favour when the painting passed uncropped to Robert Lytton on Forster’s death in 1876. But who then went out of favour with someone at Knebworth some time later, to the extent that he was obliterated from the picture.

There will be many candidates to fit the general description of the Victim. Robert, the First Earl of Lytton (1831-1891), son of Edward the novelist, owner of Knebworth after his father’s death in 1873, legatee of the painting in 1876, had many detractors and not a few enemies. That’s because Robert was considered by many to have done a poor job as Viceroy of India during his short appointment to that august post from 1876 to 1880.

“His tenure as Viceroy was controversial for its ruthlessness in both domestic and foreign affairs, especially for his handling of the Great Famine of 1876–1878 and the Second Anglo-Afghan War.”[3]

Robert was clearly an unpopular character, and might well have made an enemy of someone who had been his father’s friend – someone who many years earlier had modelled the part of the Monk in the painting.

The next heir, Robert’s son Victor, the Second Earl (1876-1947) made fewer enemies, if you except the entire population of Japan, who he upset in 1932 when he published a Report on behalf of the League of Nations, recognizing Chinese sovereignty over Manchuria and ordering the Empire of Japan to withdraw. As a result, Japan left the League of Nations in high dudgeon. I think we can, however, for the present purposes overlook this blip in Victor’s otherwise blameless career, because the person who was between 30 and 50 years old when he modelled for the Monk in 1851 would need to be still active at around 120 years of age in order to fall out with Earl Victor in 1932. And he might also need to be Japanese.

Having discovered that there might be any number of men who might be the original for the Monk, all we need to do now is find a precise physical match for the Monk as he appears in engraved image.

I’m sorry, readers, but I regret that I have failed you. I have no idea who was the model.

However, in browsing through online images I have come up with just one possible resemblance which, although entirely inconclusive, you might at least find a bit interesting.

Compare the Monk’s physiognomy with that of the up-and-coming novelist and politician Benjamin Disraeli (born 1804), a close friend of Edward Lytton and mentor to his son Robert. Disraeli was of Jewish descent, so it would be a great joke among the group of friends around Edward Lytton to cast him as a disenchanted Monk. See what you think about these images of Disraeli from around the time when Maclise painted the picture. Just an idle suggestion.

Unfortunately, if the likeness is established to be true, it undermines my arguments for Scenario #5, because I can’t find a record of Disraeli becoming unpopular with any of my Suspects.

Suspects

Whereas there are myriad potential victims available for identification as the model for the Monk, there is only a small number of potential suspects who might be responsible for his disappearance from the painting. The group must be confined to those at Knebworth who would have been in a position to decide to crop the painting during the years under discussion.

Lord Edward Lytton the novelist is excluded, because he died in 1873, before the painting arrived at Knebworth, and we have photographic evidence to show that the Monk was present and correct when it was first hung in the State Drawing Room after 1876.

So what about the next heirs, the unpopular Earl Robert, and his successor, Earl Victor? I must dismiss them as possible culprits because Jill Campbell at Knebworth says:

“knowing what I do of Robert Lytton and his son Victor Lytton and their appreciation of art, I find it hard to believe they would have approved of the cropping without very good reason.”

That only leaves the Ladies in the Case, at whom, I fear, the finger of suspicion must point:

- Earl Robert’s widow Countess Edith (1841-1936), who survived him by some 45 years, living at Homewood, a house on the Knebworth estate designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens.

- Earl Victor’s wife Countess Pamela (1874-1971), who employed Lutyens to modernise and de-Gothicise Knebworth.

- Earl Victor’s sister Lady Emily (1874-1964), a prominent Theosophist, militant Vegetarian and proto-hippie, who was married to Lutyens.

- Earl Victor’s other sister Lady Constance (1869-1923), one of the most militant of the militant Suffragettes, living with her mother at Homewood.

Each of these redoubtable ladies deserves a paragraph – indeed a whole Random Treasure blog post – to herself. Any one of them, or any combination, might have been responsible for cropping the Monk out of the painting. Or indeed none of them, because although this Scenario #5 is my favourite, it is amenable to a couple of objections which might knock it sideways:

- First, you might argue that there’s no way that the Monk could have been a likeness of a friend of Edward Lytton in the first place. Surely it stands to reason that Maclise wouldn’t give such a sinister part in the Almonry tableau to one of his mates? I can understand this argument, but would counter it by reminding you that the group of friends were keen amateur actors. Casting a pal in the role of the villain of the piece might simply be a bit of fun and not an indicator of antipathy.

- Second, you might argue (as you did in the case of Scenario #4) that a violent antipathy to the gentleman who appears in the painting dressed up as the Monk, wouldn’t be a strong enough reason to have the whole composition cut down. You could simply and cheaply paint out the Monk’s face and replace it with an imagined face, or the face of a real someone who’s much nicer. I accepted the force of this argument in relation to Knebworth visitors who might think the appearance of a gloomy Monk in the picture to be a real downer; but I think it weaker in relation to the Knebworth family if their objection was not to the Monk but to the real person portrayed as the Monk. You could overpaint the hateful Monk as much as you like, but you’d always know that he’s still there underneath.

I’m not keen on either of the two objections above, but have to admit that they might make the whole of my shaky Scenario #5 just a tad shakier.

In conclusion …

And there you have it. I’ve set out the facts of the case in forensic detail, have provided you with shedloads of background information, and have used exquisite deductive reasoning to adduce five scenarios, each offering a detailed theoretical explanation for the Missing Monk Mystery. But sadly, (as I suspect you have suspected all along) I can’t ultimately give you a definitive solution.

So have you wasted your time in reading to the end of this inexcusably long and rambling blog post? No, I don’t think so, because I still believe that the Mystery is capable of being solved. The Knebworth archives are extensive. Multiple other resources for research exist, many of them in digital form. Some documentary evidence must be able to be found somewhere to show why the Monk came to be cropped out of the painting, and who was responsible for the cropping.

But I regret that the task will take more time and effort than I have available. My hope is that reading this blog piece might stimulate someone else to take it upon themselves to continue the search. What a project for a dissertation or a thesis! What a potential triumph for the person who discovers the solution!

Jill Campbell, the archivist at Knebworth says, in relation to the cropping of the Monk:

“I have yet to find any record of this being done, so remain in the dark as to why it occurred. If I do ever find out I will let you know!”

My hope is that Jill will indeed pursue the quest, or perhaps that the publication of this piece will cause the Missing Monk Mystery to come to the attention of the current owner of Maclise’s Caxton painting, Henry Lytton Cobbold, 3rd Baron Cobbold, who is a writer and blogger himself. If Lord Cobbold is ready to focus his attention and resources onto the problem, perhaps eventually a solution might be found. I hope so.

Notes

[1] https://www.tatler.com/article/inside-the-marriage-which-helped-quirky-sir-edwin-lutyens-rise-to-be-societys-favourite-architect

[2] https://apollo-magazine.com/william-powell-frith-private-view-royal-academy/

[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Bulwer-Lytton,_1st_Earl_of_Lytton