In Chapter 1 of this extended blog post, which you can read here, I told you about a painting hanging in Knebworth House, Hertfordshire, which used to contain a depiction of a miserable-looking Monk, but from which the aforementioned ecclesiastical personage has mysteriously disappeared. If you haven’t read Chapter 1, then this Chapter 2 won’t make much sense, so I suggest that you go back and read it now. If at that juncture Chapter 2 still doesn’t make much sense, then I won’t be altogether surprised. You might be dismayed to learn that there will also be a Chapter 3.

Although the Monk is absent from the painting hanging today in the Knebworth State Drawing Room, we know he was there at one time. Lord Lytton took pains to describe him in detail; and he’s present at the left-hand side of the artist-approved engraving which hangs in my study, as you can see here:

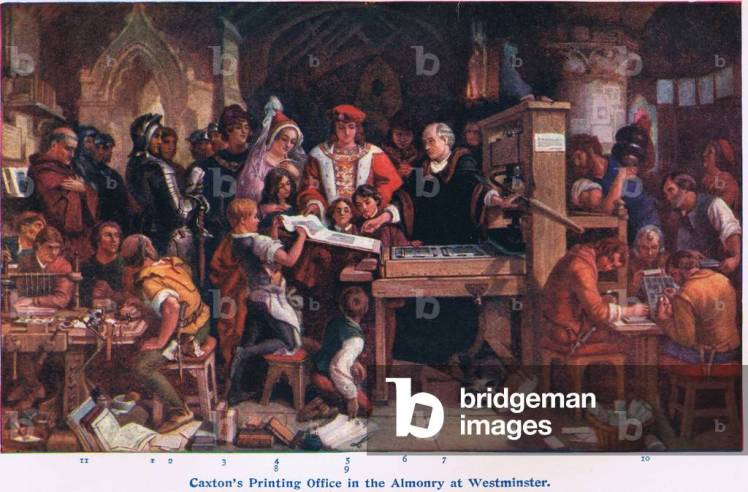

The monk is also present in one of two early 20th century colour reproductions of the original painting which appear in the Bridgeman Images online archive [1]. Here he is, reportedly from a history book published by Cassells in the 1920s:

But in the second Bridgeman image [2] (unfortunately undated), he’s gone. Look:

There’s no dubiety: the Monk was there at one time at the left of the oil painting, but he was removed and he’s not there now.

I’m ashamed to say that when I originally researched the 1851 painting and the 1858 engraving, and then wrote about them both in my previous blog piece, I didn’t clock that the Monk had gone missing. This fact was pointed out to me by a Random Treasure blog reader called Caroline, who contacted me a few months ago. Caroline had bought in a charity shop a jigsaw puzzle featuring a colour reproduction of the monk-less version of the Maclise painting.

Finding that the jigsaw image wasn’t credited to an artist, Caroline had gone online to check out the painting and its painter. In the process she had come upon my blog post, which includes not only a photo of my black-and-white engraving, but also a colour reproduction of the picture as it hangs in Knebworth House today.

And unlike me, Caroline had spotted the difference. In the engraving, a Monk; in the jigsaw puzzle and in the Knebworth oil painting, no Monk.

She wondered if I knew why, and where the Monk had gone? Red-faced at having failed to spot the glaring discrepancy, I replied that I had no idea but would try to find out. I would attempt to solve The Missing Monk Mystery.

I donned my deerstalker hat, got out my magnifying glass, played a couple of lieder on my Stradivarius violin, smoked three pipes of black shag, drank a cup of Mrs Hudson’s excellent coffee, briefed Watson, and injected myself with a narcotic substance. I was ready to start my Investigation.

Now for some fine detail. If you compare the coloured Bridgeman Archive images reproduced above, you’ll see immediately that one is wider than the other. In the wider version, towards the left, there’s a bloke in armour (this is Lord Rivers – we’ll talk about him later), with a hooded figure standing behind and to his left. In the foreground below, a workman in a yellow jerkin sitting at a workbench engraving a woodblock. Further to the left, in the foreground at the edge of the picture, are three more seated workmen, engaged in various bookbinding processes. Above them stands the scowling Monk with three soldiers.

Now look at the narrower version. The Monk and everything below and behind him are missing. They have been chopped off.

It’s the same on the right-hand side of the painting. In the wider image, three typesetters; in the narrower, they’ve been chopped off too.

The image below shows the current version (as featured in the Bridgeman Images archive) superimposed over the whole composition as shown in the engraving. The now-missing bits are outlined in red.

Yes, the current painting shows only the central part of the original composition. That’s how it looks in Caroline’s jigsaw, and that’s how it looks in Knebworth House today. And yet we know for certain that when the painting was first shown in 1851 it was complete with the Monk, the soldiers and the workmen.

As a starter for my Investigation, I thought it might be helpful to try to work out how much was missing from each side of the painting. This was tricky because the catalogue for the 1851 Royal Academy Summer Exhibition, where it was first shown, doesn’t provide a size for the original image. I had to make an estimate.

Assuming that my engraving, signed by Maclise, is in the same height-to-width ratio as the full-size painting, and scaling the size of the engraving up to the published dimensions of the cropped painting as currently on display at Knebworth, I calculated that about 24 cm (a bit over 9 inches) has been shaved off on each side.

How odd that a celebrated artwork, much loved and admired by its owning family, and displayed in pride of place in the family’s gigantic stately home, should have been mutilated by being reduced in width. Who on earth would do that? Why on earth would they do it?

It wasn’t a problem that could be solved by deduction alone. I needed more information. Who might be in a position to help me towards a solution to the Mystery?

I took the bull by the horns and phoned Knebworth House, asking to speak to the person in charge of the pictures. The telephonist put me on to Jill Campbell, the incredibly helpful Knebworth archivist, who undertook to look into the Mystery.

Information provided by Jill in response to my call has been invaluable to the progress of my Investigation.

First, Jill told me this tale about the history of the painting and how it came to be at Knebworth:

“The painting was commissioned by John Forster, who at his death in 1876 bequeathed it to Edward’s son Robert, 1st Earl of Lytton, to remain at Knebworth House by descent. Forster was very much a father figure to Robert, having been good friends with both Robert and his father Edward.”

This was important new information, correcting and expanding upon what I had been able to find out previously, which was (to quote myself in my 2018 blog post): “after the RA Exhibition, the painting passed into the ownership of the writer John Forster. … and when Forster died, it was acquired by the novelist Edward Bulwer Lytton”.

John Forster was a prolific art collector. In his will he left his collection of pictures to the South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria & Albert Museum). If, as Jill reveals, he excepted Maclise’s important Caxton painting from this gift in order to bequeath it to Robert Bulwer Lytton, then it must say something about the closeness of the relationship between Forster and Robert’s father, Edward Lytton.

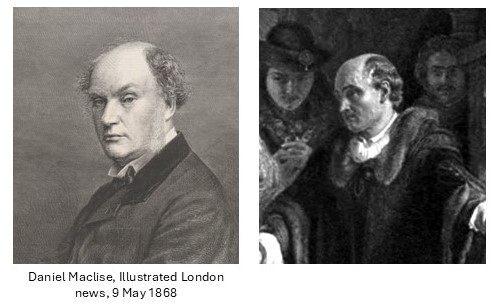

Forster was also a close friend of Charles Dickens, and of Daniel Maclise. Among other joint activities, the four friends engaged in amateur theatricals at Knebworth. I feel sure that there’s a book to be written (but not by me) about this extraordinary group.

The relationship between these big Victorian personalities matters for my Investigation because of the next interesting detail supplied by Jill, which concerns one of the figures shown in the painting:

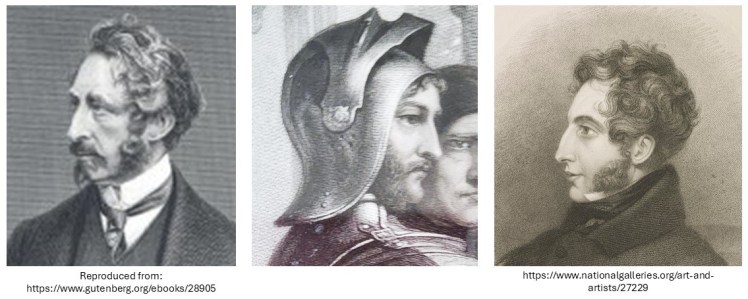

“Edward Bulwer Lytton appears in the painting, in armour as Lord Rivers, the Queen’s father.”

I asked Jill if she has documentary evidence to support this assertion, but she doesn’t. It’s a Knebworth family story. But if you compare likenesses, you can see a strong resemblance between the real-life Lord Lytton in some contemporary portraits and the re-imagined Lord Rivers in the painting and engraving. It’s pretty convincing: Maclise has included a portrait of his friend Lytton in his picture.

OK, so the appearance of Lord Rivers seems to be based on that of Lord Lytton; and I have already argued in my previous posting that the appearance of Edward IV’s Queen, Elizabeth Woodville, seems to be mightily close to that of the young Queen Victoria.

I wonder if we can therefore surmise that other figures in the painting might also be based on real-life celebs or characters within Maclise’s circle of friends and acquaintances? Maybe we can. I’m sure there’s another book to be written here (but not by me), or at least an undergraduate dissertation. For starters, might Maclise’s depiction of William Caxton be an idealised self-portrait?

The intriguing possibility that Maclise’s cast of characters in the painting might have identifiable real-life equivalents might or might not be helpful to the course of my Investigation.

The next snippet of helpful information from Jill Campbell was absolute confirmation that at the time of its arrival at Knebworth in 1876, the painting was complete with the Monk and the other now-missing figures:

“I found a photo of the State Drawing Room dating from the late 1800s [below] … showing the Maclise painting. It has a lot of light reflection on it, but I think that it does show more at the sides than now. This can be seen clearer on the left side, with the man looking upwards behind Bulwer Lytton in armour has another 2 people seated beside him & we can see all of the man with his head bowed & clasped hands. Also, the white shirt sleeve of the man seated on the right side can be seen. If I am right, then it means that the cropping has occurred since the painting has been at Knebworth House.”

And next, Jill provided an expert witness statement that the painting had indeed been cut down:

“In 2007 experts from the Hamilton Kerr Institute [3], University of Cambridge, carried out a full examination of the painting when it went to them for conservation work. The report states that ‘the left and right edges of the canvas have been cropped, reducing the size by approximately 28 cms on both sides. Removing a damaged section from one side of the canvas and mirroring the removal on the opposite side in order to retain compositional balance could be a possible reason for this intrusive treatment.’”

I’m gratified to note that my estimate of 24 cms missing on either side is quite close to the professionals’ estimate of 28 cms. Not bad for an amateur, though I say so myself (no-one else is going to say it).

It’s difficult to get a fix on when the cropping took place. We know the Monk was present in “the late 1800s”. But another photo taken of the painting [4] when it was displayed in an exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery, London, in 1972 shows that he’d disappeared by then. This gives us a window of getting on for 100 years during which the Monk might have taken his departure.

The background having been laid out in full, the task remaining to the detective is now to apply the deductive reasoning which will solve the Missing Monk Mystery. If only.

What we know for certain is:

- that the Monk was a character particularly worthy of notice in the original painting

- that he disappeared at some point between the late 19th century and 1972.

We don’t need to find out where he and the other missing characters went after their excision from the painting. Presumably either up in smoke or into the bin.

But we do need to find out why he went and who was responsible for his departure.

I have five possible explanatory scenarios to offer you. More may be available but I’m not a clever enough detective to have thought of them. In Chapter 3 of this blog post you’ll find the scenarios and maybe (or maybe not) the solution to the Missing Monk Mystery.

Click here for Chapter 3 of the Missing Monk Mystery

Notes

[1] https://www.bridgemanimages.com/en/maclise/caxton-s-printing-office-almonry-westminster/lithograph/asset/931057?offline=1.

[2] https://www.bridgemanimages.com/en/maclise/caxton-s-printing-press-1851/nomedium/asset/28216

[3] https://www.hki.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/

[4] https://photoarchive.paul-mellon-centre.ac.uk/objects/427779/caxtons-printing-office