Note to Readers

If you have read the most recent post in this blog, you might be expecting to find here the second instalment of my peroration on Fictile Ivory, which is to be an attempt, after further enquiry, to answer some Unanswered Fictile Questions. Apologies, but I’m afraid my investigation is not yet complete, so there will be a delay – which might cause disappointment for some readers but relief for others.

In the meantime your blogger’s attention has wandered. The piece below is about Four Heroes. And next – before this blog returns to fictile matters – there will be a new post telling the tale of a Missing Monk Mystery (Unsolved).

Four Heroes

If you look back through my previous 101 posts in this blog, you’ll mostly find stories about artefacts: ceramics, books, paintings, engravings, woodwares, sculpture, furniture, textiles, rugs, and more. But in all of those posts you’ll find virtually nothing about objects associated with wars or fighting or armaments or heroes.

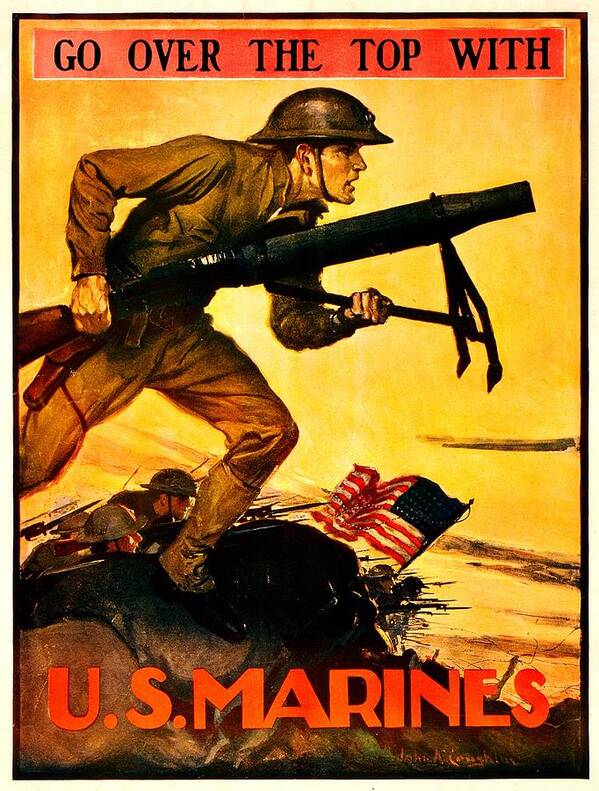

Growing up in the 1960s as a timid namby-pamby wishy-washy anti-war left-wing metropolitan Jewish intellectual liberal hippie, I never developed an admiration for military memorabilia alongside my passion for many other categories of artworks and antiques. Militaria just doesn’t interest me all that much. Guns and swords and uniforms and medals and badges and trench art are eagerly sought out by collectors, and can fetch very high prices. But they are not for me.

What’s more, I don’t really take to military heroes: those soldiers and sailors and airmen who are ready and willing, often eager, to risk everything for their country, for their monarch or republic, for their class, for their race, for the revolution, for freedom, truth and justice. Because all too often such apparent selflessness and patriotism is alloyed with less altruistic motives: with colonialism, imperialism, racism, xenophobia and fanaticism. And above all with egotism, with the quest to earn personal glory, reputation and admiration through the conspicuous exercise of overweening bravado, cruelty, sadism and machismo. Add in an often-present addiction to risk, danger and self-harm, and the whole confection can become a little too toxic for my peaceable tastes.

I can admire or marvel at individual acts of courage and self-sacrifice, but as a general class of behaviour I don’t find such swaggering, often public-school-educated hubris-driven heroism especially interesting or attractive.

What I admire more is the heroism seen among conscripts and volunteers and would-be bystanders, whose loyalty, steadfastness and courage stems wholly from a sense of decency, duty or loyalty; those who face risk and danger quietly, overcoming private feelings of fear and reluctance. You don’t hear so much about them.

And yet for me it’s an entirely different matter when it comes not to heroes but to superheroes. I’m delighted to hero-worship them, just as long as they are larger-than-life and colourful and fantastical and magnificently remote from anything resembling real life in their struggles against evildoing. As a child, I avoided comics like the Victor or Boy’s Own, replete with stories of derring-do and gung-ho medal-winning foolhardiness on the front line. But if I could get my hands on an imported DC or Marvel comic featuring Superman or Batman or Green Lantern, then I’d devour it voraciously. Similarly, when it came to borrowings from the public library, I was delighted with anything far-fetched and remote from reality – be it Greek myths or sci-fi – but underwhelmed by Biggles.

In the pantheon of all-time superheroes, two of my fictional favourites are Odysseus and Lawrence of Arabia.

Odysseus is of course the hero of Homer’s epic the Odyssey, written in Greece in the 8th century BC, the adventure-filled story of the title character’s perilous ten-year journey home to Ithaca from a decade of military action in the Trojan war.

My initial encounter with Odysseus was in a book borrowed from the Marylebone public library, perhaps at around nine years old. I remember a thick book with a blue cover, and after much online searching I’ve concluded that it must have been from an eight-volume series entitled The Children’s Hour, published in the 1920s by the Waverley Book Company. Volume III, Stories from the Classics, contained a potted version of The Odyssey which had me rivetted. It was illustrated in vivid colour by the artist Charles Edmund Brock, and I have a clear memory of being terrified by the picture of the giant cyclops Polyphemus, and having nightmares after reading the tale of his blinding at the hands of the superhero Odysseus.

As for Lawrence of Arabia, you might protest that he wasn’t a fictional character at all but a real-life soldier called T E Lawrence. But such arguments would be useless with me. In my mind the superhero Lawrence of Arabia and the soldier Colonel Thomas Edward Lawrence (1888-1935) are and will always be two entirely separate entities, one a superheroic fictional construct, the other a brave but flawed historical character.

I love the former, but find myself pretty indifferent to the latter, except in one respect which I’ll come to later.

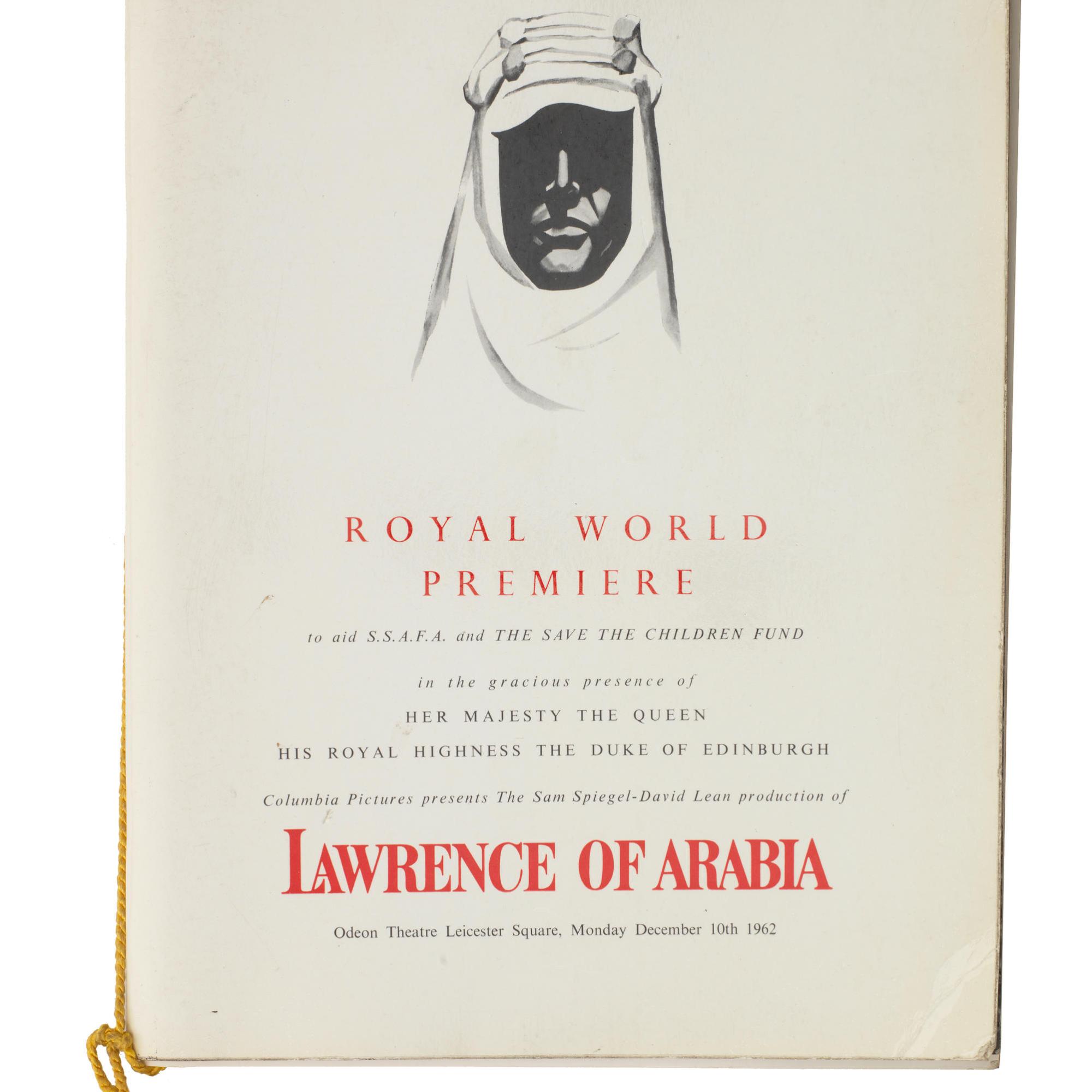

Let me attempt to trace the origin of this strange bifurcation. Please accompany me back in time to an afternoon in December 1962. Observe me in the Odeon Cinema, Leicester Square, London, watching the new movie Lawrence of Arabia, directed by David Lean. The cinema is the most luxurious and technically-advanced picture-house in Europe, with the biggest and best screen, where the movie received its world premiere a few nights previously, in the presence of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II and also in the presence of my parents Peter and Diana Stewart.

I am two months past my fourteenth birthday, and my Mum and Dad, having already seen the movie, have given me a special dispensation from compliance with the British Board of Film Censors’ “A” Certificate, which would have otherwise required me to wait until my 15th birthday.

The film hasn’t yet gone to general release, so I’m one of the first few thousand people in the world to see it. My seat is in the front row of the Grand Circle, commanding the costliest and best view in the house. The film is shot in eye-popping 70mm Super Panavision CinemaScope Technicolor, and lasts 222 minutes, a little longer than Gone with the Wind. It will go on in early 1963 to be nominated for ten Oscars, of which it will win seven, including Best Picture. Over time it will consistently be highly placed in listings of the one hundred best films of all time.

In my impressionable early teens [1], I’m spellbound throughout the entirety of the film by its mythical qualities as evoked by its director: endless desert vistas, hordes of Arab fighters on camelback and horseback, guerilla warfare, train wrecks, exotic costumes, manliness, cleanness, cruelty, violence, privation.

Above all, Peter O’Toole starring as Lawrence, with his piercing blue-eyed gaze, fulfils all the standard requirements for a superhero: distinctive and somewhat ethereal appearance; survival against overwhelming odds; uncanny strength and durability; an iron will; superpowerful charisma to attract the devoted following of the masses; a hint of kryptonite vulnerability; scepticism from those in authority (Jack Hawkins as General Allenby channelling the Mayor of Gotham City); a fancy costume; and a tendency to behave in a way that no real human being has ever actually behaved.

Is it any wonder that Lawrence of Arabia becomes and remains my Number One Teenage Superhero? Is it any wonder that for me, the Lawrence of Arabia who exists inside the movie is fixed as a separate and distinct being from the real Colonel Lawrence?

Since that day more than six decades ago the myth embodied in the cinematic Lawrence has satisfied me to such an extent that I’ve never taken the trouble to find out much about his real-life counterpart: Colonel Thomas Edward Lawrence (16 August 1888 – 19 May 1935), a.k.a. 352087 Aircraftsman John Hume Ross, a.k.a. T E Shaw. If you’re curious you can look up his biography online[2] and get a huge quantity of detail about him, much of which was authored by the man himself, and much of which, as I understand it, doesn’t stand up too well to close scrutiny.

From what little I know, the real T E Lawrence is a heroic but highly controversial and enigmatic character who seems to match up in many ways with the hubristic and self-aggrandising description of English Public School heroism which I set out earlier in this piece.

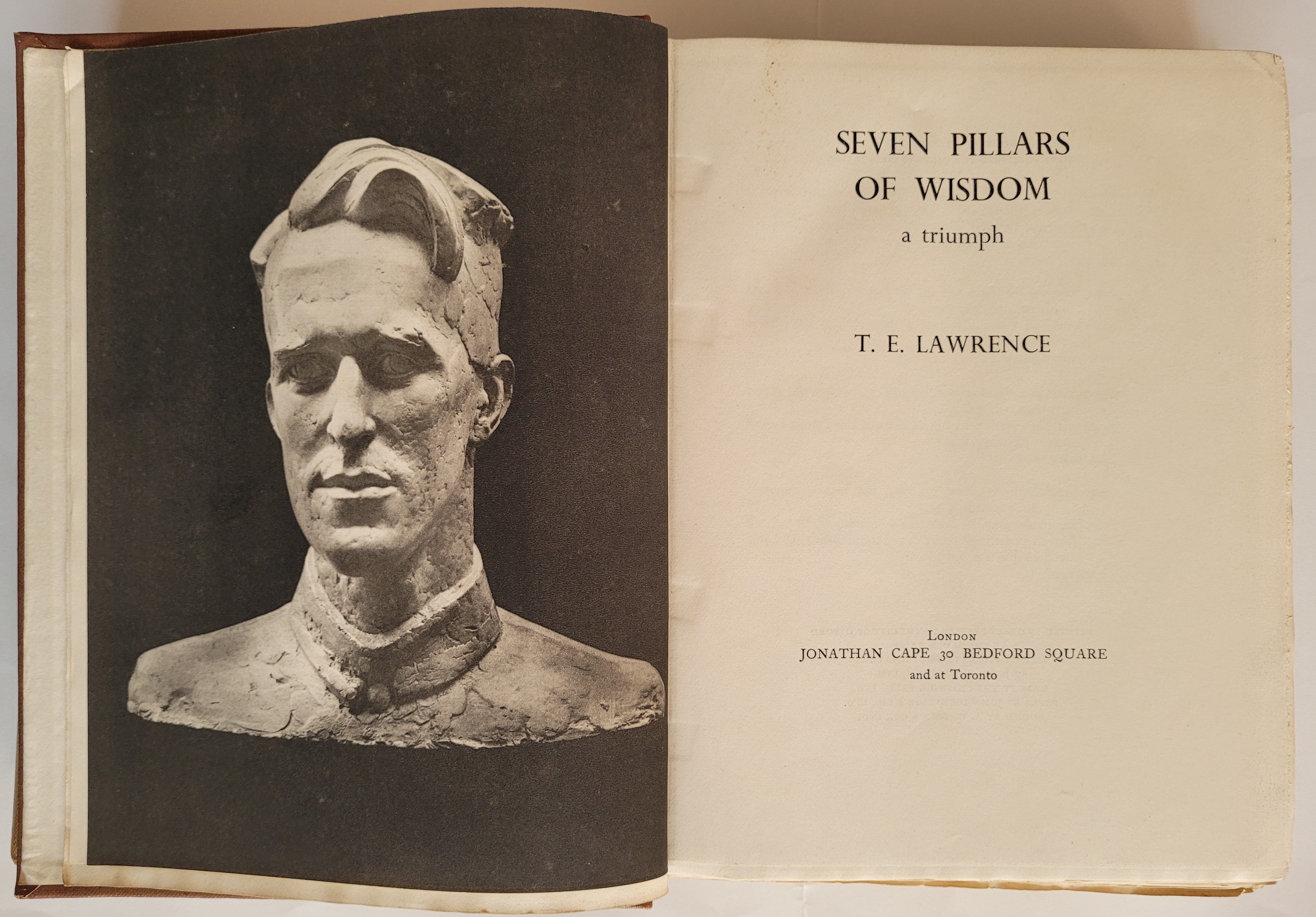

And yet, in one important respect, I’m a huge fan of the real Lawrence. I love his books. Not, admittedly, as works of literature. Frankly, I don’t know if the books are any good or not because I haven’t read them, deterred by their general subject matter and also by the subtitle A Triumph attached to his 629-page autobiographical masterwork Seven Pillars of Wisdom. That subtitle, plus the choice of a picture of a statue of himself as the frontispiece to the book, tell me as much about Lawrence as I wish to know.

But I love Lawrence’s books as objects, as artefacts.

Seven Pillars of Wisdom: a triumph is by far Lawrence’s best known work. The book has a complicated printing history, but the first UK edition for general circulation was published by Jonathan Cape in 1935. I own a splendid copy of the first printing of this edition, and it’s a beautifully printed and illustrated book of 672 pages, bound in brown buckram boards with bright gilt spine lettering, the front board stamped in gold with a crossed scimitar device, the outer and lower edges untrimmed as issued. Some leaves in my copy are uncut, indicating that the book is not only unread by me, but also by anyone else.

In addition I have a fine 1927 fifth impression of Revolt in the Desert, similarly bound in brown buckram, and a first edition of The Mint (blue buckram, complete with dust jacket), which Lawrence wrote under the name of Aircraftsman Ross, and which was edited and published posthumously in 1955.

They are handsome, chunky, expensive-looking books, and I’m delighted to own them in spite of the fact that I have no intention of ever reading them. And I’ll always be on the lookout for any other title by Lawrence which might happen to come my way, in the hope of eventually assembling a full set of his superbly-produced publications in good condition.

Which is why I was surprised but disappointed in a charity shop a couple of weeks ago on finding a copy of T E Lawrence’s translation of The Odyssey of Homer, written under the pseudonym T E Shaw. Surprised because I hadn’t known that he had made a translation of Homer’s epic featuring my favourite superhero Odysseus. Disappointed because this copy, published by Humphrey Milford at Oxford University Press, and labelled on the reverse of the title page as a first UK edition from 1935, was decidedly worn and battered and clearly unfit for display on my bookshelves alongside the other Lawrence titles. The cover boards are dented and soiled. The spine is faded and frayed. The pages are dirty and yellowed, and some have been scribbled on in purple crayon. It’s a mess.

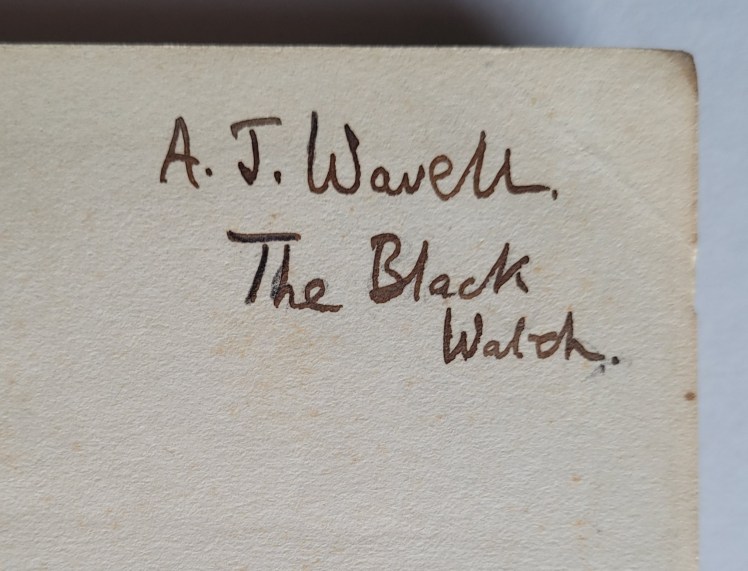

But then, just before deciding disconsolately to give the book a miss and return it to the shop shelf, I happened to notice a small handwritten inscription on the flyleaf. A J Wavell, the Black Watch.

Standing there in the shop, I thought: Wavell? Black Watch? Familiar name, familiar regiment. There was an extremely big cheese in the Second World War called Wavell. Could this beat-up old book have belonged to him? What could it tell me? Could I maybe find some compensation for the poor condition of this volume by glamourising it with important provenance?

Without further hesitation I paid the rather steep £10.00 price tag and rushed home with the book to start my research.

One minute or less of googling revealed that Field Marshal Archibald Wavell, 1st Earl Wavell, GCB, GCSI, GCIE, CMG, MC, PC (5th May 1883 – 24th May 1950), was the Regimental Colonel of The Back Watch, a military leader, a diplomat and a hero extraordinary. A General from the age of 34, he was wounded in the Second Battle of Ypres in the First World War, losing an eye. In the Second War, he served as Commander-in-Chief Middle East, Commander-in-Chief India, Commander of American-British-Dutch-Australian Command and finally as Viceroy of India.

Aside from his innumerable military exploits, Earl Wavell was an accomplished writer and poet. He was also a friend of T E Lawrence and a tremendous admirer of him as a man, as a soldier and as a military strategist. Wavell wrote:

“He will always have his detractors, those who sneer at the ‘Lawrence legend’; who ascribe his success with the Arabs to gold; who view the man as a charlatan in search of notoriety… They knew not the man. Those who did, even casually and sporadically, like myself, can answer for his greatness”.[3]

Wow! What an exceptionally distinguished former owner of my copy of the Odyssey!

But then I looked harder, and – disaster! – discovered that Field Marshal Earl Wavell had the middle initial P for Percival, and not the middle initial J as in the signature on the book’s flyleaf.

Oh dear. Wrong Wavell. Possible waste of ten quid.

If only I had got the right Wavell, I could have boasted to you, blog readers, that my charity shop copy of the Odyssey was an object of huge significance in its joining together of Wavell and Lawrence, two military titans. I might even have suggested that although unsigned by the author, this book might have been personally presented by Lawrence to his friend Wavell. This would, of course, have been an entirely spurious claim, because this 1935 UK edition of the Odyssey wasn’t published until shortly after Lawrence’s tragic superhero’s death astride his Brough Superior motorcycle.

After this let-down, I still needed to find out about the A J Wavell of the Black Watch whose name is on the flyleaf of my book. It didn’t take long to discover that he was Major Archibald John Arthur Wavell, MC, the 2nd Earl Wavell, (11th May 1916 – 24th December 1953), only son of the more famous 1st Earl.

Not a let-down at all: another Earl, and another military hero, who fought through the Second World War, losing a hand while winning his Military Cross fighting with the Chindits in Burma. Succeeding to the earldom in 1950 upon his father’s death, he was shot and killed just three years later during the Kenya Emergency, as he led a joint patrol of Black Watch soldiers and Kenyan police in pursuit of a gang of Mau Mau rebels.

Archibald John Wavell was Archibald Percival Wavell’s only son, and he had no issue, so the title of Lord Wavell became extinct on the 2nd Earl’s death. I can’t tell you very much more about him than this. Unlike his father, he isn’t extensively or exhaustively memorialised. What records I can find about the son show him to be a conscientious professional soldier and middle-ranking military leader, and a hero in his father’s mould. But unlike with his father, there’s no information about whether he was a bookish sort of chap, so it’s not possible to say how he felt about his personal copy of T E Lawrence’s Odyssey of Homer.

A J Wavell would certainly have known that his father was a friend and admirer of the legendary Lawrence of Arabia. Aged 19 at the time of Lawrence’s death, it’s quite possible that A J met Lawrence face-to-face, and that the real-life Colonel Lawrence was as much of a teenage idol to him as his cinematic counterpart was to me.

If this is the case, then perhaps we can surmise that A J Wavell’s copy of Lawrence’s Odyssey might have been one of his prize possessions. Who knows but that he himself was responsible through repeated reading for its well-thumbed pages and its battered covers? Was the book an essential item in his meagre bachelor soldier’s kit, carried from one posting to the next during his military career? Was it on his nightstand in Nairobi on the morning that he set out on his fatal final patrol?

We can’t know. We can really only imagine what the 2nd Earl Wavell’s feelings were about this book. Neither can we have any idea how, 72 years after his death, it turned up in a charity shop in Leith.

All we know is that the book stands as an extraordinary link between four great military figures, mythical and real: Odysseus of Ithaca, Lawrence of Arabia, the First Earl Wavell and the Second Earl Wavell. Perhaps the book symbolises some sort of heroic continuity through two-and-a-half millennia.

Unimpressed as I am generally with the whole concept of military heroism, I find something strangely moving about this notion. So I’m pleased to welcome this very special book to my collection of Random Treasure.

[1] How I came to view the movie in such extraordinarily privileged circumstances isn’t relevant to this blog post, but I’ll be happy to explain if anyone wants to know.

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/T._E._Lawrence

[3] Quoted at https://www.greatwarforum.org/topic/262512-lawrence-deraa-and-the-10th-motor-detatchment-war-diary/

Thanks for another interesting article, Roger. As I read this I was trying to think why the name Wavell was so familiar, despite my lack of any detailed military history. It’s through poetry anthology my mother appears to have bought in a paperback issue c.1960, which is called “Other Men’s Flowers”. First published in 1944, it was compiled byA P Wavell and dedicated to his son “who shares my love of poetry, but thinks his father’s taste a little old-fashioned”. The poems are apparently ones which Wavell knew by heart – and I happened, some weeks ago, to have put my mother’ copy beside the documents for a forthcoming holiday as I wanted to copy one poetic extract she regularly quoted. It’s “The Golden Road to Samarkand” and I will think of her when I’m there next month. I hope the two Wavells literary links appeal to you – and that you might decided to add a first edition of Other Men’s Flowers to your Wavell collection. And as your post and this have been about parents and children, do tell how you came to be at the film …

LikeLike

Thanks Anne. I had read about Other Men’s Flowers when I was writing the blog but didn’t take the trouble to look at the book. I’ve now had a quick scan of the online version, and will indeed look out for a nice early copy for my bookshelves. Perhaps A P Wavell was a more sensitive soul than your average Field Marshal, and perhaps his son A J Wavell, with his taste for modern poetry, was less the simple soldier, and more of a complex and thoughtful individual than I had glibly assumed.

As for my teenage connection with the Odeon Leicester Square, the explanation is that my parents were the landlord and landlady of the pub closest to the cinema in Charing Cross Road. We lived in the upper floors of the building. In that pre-online-booking era, the cinema had several members of staff working in the box office, all of whom developed raging thirsts during the working day, which required to be slaked with copious quantities of alcohol after knocking-off time. My congenial Dad developed close over-the-bar-counter friendships with these characters, and found that treating them to a Scotch or two would invariably result in the presentation of complimentary tickets for the big film premieres. My elder brother and I often received tickets for a showing a day or two later.

By the way, I’m extremely envious of your trip to Samarkand. Will you also be making other stops on the Silk Road?

LikeLike

Poetry was a big thing in those days – people were surprised when I mentioned in my last book that Ernest Shackleton was a VP of the Powtry Society! Great film woeld story … is the pub still there? We’re just going to Uzbekistan – as did Ella Christie of Perthshire’s Japanese garden – whose book I’m thaking with us – so Khiva, Samarkand, Bakhara and Tashkent. Can’t wait!

LikeLike